While we may be able to appreciate a disruptive innovation in retrospect, it is debatable whether we can convert our understanding into a formal, repeatable process. In today’s turbulent environment, leading disruptive innovation is likely more about best principles than best practices, and requires a disruptive approach to management itself. Down with convention, then, and up with what this author terms LEAPS, an original but potentially very effective way of leading and managing disruptive innovation.

In today’s complex, dynamic world, having a disruptive innovation capability is mandatory, both for growing a business and protecting existing markets. But leading disruptive innovation requires new mindsets and behaviours, for leaders themselves and for the organizations that develop them. This author describes the qualities and competencies required for leading disruptive innovation

Disruptive innovation that transforms or creates new markets has become the Holy Grail for many companies. Books like The Innovator’s Dilemma[i], along with Apple’s remarkable success and the high-profile failures of Blockbuster, Borders, and Kodak, have created a heightened awareness and a desire for game-changing innovation. More resources, models, and tools exist to help companies innovate than ever before.

Leaders today, however, face a big challenge when it comes to disruptive innovation. Many executives rise through the ranks of management, where predictability and control are valued and rewarded. Unlike operations management, disruptive innovation – whether creating it or responding to it – involves extreme uncertainty. Unexpected events, inevitable failures, and a fundamental lack of control are inherent to the process. But few leaders are formally prepared to deal with the realities of leading or responding to disruption.

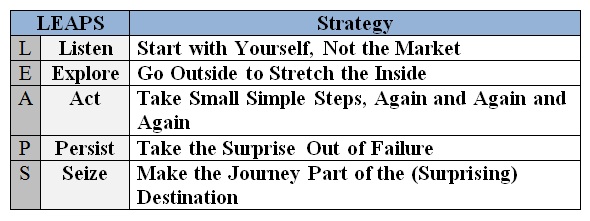

This article highlights the key dynamics involved in leading disruptive innovation. My goal is to outline the core leadership experiences and practices involved in the process. A five-phase model, using the acronym “LEAPS,” provides a structure for understanding the ways leaders create clarity during times of great uncertainty. This model was developed during the research for my book, Leapfrogging[ii]. In addition to specific company examples, empirical research from U.S. and European universities provides insight into some of the more subtle social and psychological success factors that distinguish leaders who are best suited to drive disruptive change.

Leaping into uncertainty

Perhaps the most defining characteristic of disruptive innovation is the great uncertainty that it creates for leaders, organizations, and entire industries. The music, entertainment, computing, mobile phone, book publishing, photography, and healthcare industries have all experienced dramatic change due to new technologies, business models, distribution channels, government regulations, and market expectations. Companies in these industries have been forced to experiment and introduce new technologies and business models, not just to compete, but to survive.

While most organizations possess a general awareness of the importance and necessity of disruptive innovation and change in general, there is a gap when it comes to understanding the deeper leadership qualities necessary for driving them. Many leaders rely on research and data for decision-making to manage daily operations, for example, but during times of disruption, waiting for hard data to make decisions can quickly result in failure. Leaders must be comfortable using whatever information they have on hand, integrating inputs from diverse sources around them, and then using their intuition to round out the decision-making process.

The challenge for any business is that the competencies necessary for leading disruptive innovation are not formulaic or quantifiable. As Gary Hamel says, “New problems demand new principles. Put bluntly, there’s simply no way to build tomorrow’s essential organizational capabilities—resilience, innovation and employee engagement—atop the scaffolding of 20th century management principles.” Hamel goes on to say, “In an age of wrenching change and hyper-competition, the most valuable human capabilities are precisely those that are least manage-able[iii].”

While a disruptive innovation can be seen and understood in retrospect, it is debatable whether it can be transferred into a formal, repeatable process. In today’s turbulent environment, leading disruptive innovation is likely more about best principles than best practices, and requires a disruptive approach to management itself.

Using LEAPS to drive disruption

Whether going after disruptive innovations that leapfrog competitors and customer expectations, or focusing on “blue oceans[iv]” that represent white-space opportunities to create entirely new markets, the leadership issues are similar. Leaders must embrace ambiguity, live with uncertainty for long periods of time, and confront the critiques of naysayers both inside and outside of their organizations. Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon, summarized the essence of the leadership challenge when he said, “Any time you do something big, that’s disruptive, there will be critics… We are willing to be misunderstood for long periods of time[v].” Few business schools, let alone companies, prepare their leaders to live with being misunderstood or criticized, especially for extended periods of time. When it comes to leading for disruption, recognizing that “the soft stuff is the hard stuff” can make the difference between success and failure.

I have developed five strategies to address the inherent uncertainty of disruptive innovation and change. Falling under the acronym LEAPS, each strategy contains specific principles that provide the basis by which leaders harness uncertainty, ambiguity, and even surprises to reinvent their organizations and industries.

Listen – Start with Yourself, Not the Market

Contrary to conventional wisdom, disruptive leadership is not about analyzing customer needs, creating specifications to meet each need, and building great products and services to meet them. Bob Ulrich, the former CEO of the retailer Target, was opposed to direct consumer market research, and focus groups especially. During Target’s breakthrough growth years, the Target team used its own instincts to infuse everything with leading edge design, from transforming store layouts to creating partnerships with designers like Philippe Starck. Consumers didn’t know what they had been missing when going to Wal-Mart or Sears until Target showed them how “Tar-zjay” could give them “cheap chic” in a way no other retailer could.

Leaders like these don’t get bogged down in data, but rather find opportunities to deliver an entirely new level of value. Research from the University of Amsterdam[vi] reveals the dyanmics behind how these leaders rise above the complexity of today’s business environment. Researchers found that when subjects were presented with large amounts of data, those that conducted the most analysis and spent the most time reviewing options and choices were not the best decision-makers. In fact, those who were forced to ignore detailed data through intentional distractions from the researchers used “unconscious thinking time” in their thinking process. They not only made superior decisions but were better able to recognize patterns in the complex data.

Steve Jobs and Apple never conducted market research as they developed the iPod, iPhone and iPad[vii]. Rather, Jobs and his team at Apple defined products and a user experience they, themselves, wanted. Asking the market what it wanted would have been fruitless since consumers didn’t know what they were missing until they were given it by the company. Leading through disruption involves determining what one values and where we want to make a difference – both in what we do and how we do it. Disruptive innovations come from people and organizations who “innovate for themselves” because they want to make a difference for others.

Explore – Go outside to stretch the inside

Leading through disruption requires an agile mind that appreciates ambiguity. Disruptive innovators know that uncertainty contains as much opportunity as it does risk. But to make this mindset practical, it is essential to push personal, team, and organizational comfort zones. Borders, the recently bankrupt bookseller, stuck to its retail knitting even while Amazon, Apple, and Barnes & Noble were introducing eBook platforms to transform the industry. When leaders remain safely rooted in how things are done today, they miss the kind of insight and market impact needed to protect themselves from, or create, a true disruption.

A series of research studies from INSEAD and Northwestern University[viii] sheds light on how leaders can overcome the paralysis that characterized Borders’ leadership. Researchers studied the problem-solving skills and creativity levels of individuals who have lived in two or more cultures versus those who have never lived abroad. The findings from the research demonstrates that when individuals are forced to confront competing assumptions and norms through living abroad, the boundaries of their assumptions and related defenses soften. The concepts of “the right way” versus “the wrong way” break down. Instead of responding to a challenge like a deer in the headlights, they see connections and patterns that most others don’t see and find the most creative opportunities.

Leaders who possess a track record of pushing their own personal boundaries are best equipped for tackling the gray areas. These individuals stretch their comfort zones by taking on roles spanning different functions, working across diverse industries or living in different cultures. As a result, they’re most comfotable taking themselves, their teams, and their organizations out of the proverbial corporate comfort zone and into uncharted territory.

Act – Take small simple steps, again and again and again

Paradoxically, leading disruptive innovation involves simultaneously focusing on your own intentions and motivations to make a difference, like Target and Apple did, while at the same time gathering as much external input as possible – from customers, employees, partners, or anyone else deemed relevant to the opportunity. Disruptive leadership involves putting a flexible stake in the ground around a specific opportunity, and then taking a series of actions to intentionally challenge assumptions and rapidly change direction as many times as necessary.

Researchers from the University of Virginia[ix] explored the differences in problem-solving styles and thinking between serial entrepreneurs (individuals with at least 15 years experience and who had taken one or more companies public in their careers) and professional managers from large corporations (including leaders from Shell, Philip Morris, and Nestle). Each cohort was provided a hypothetical case of a start-up and was asked how they would help it develop and grow.

The entrepreneurs first looked at the resources and information they had at their disposal, defined short-term actions, and then improvised. They looked for ways to solicit input from anyone and everyone who would listen. Their primary objective was to deliver something tangible to customers, even if it wasn’t fully developed, in order to gain feedback, challenge their assumptions, learn, and iterate to better ideas. Professional managers, on the other hand, began by listing concrete goals and plans. They too viewed customer input as important, but saw it as a single up-front input to help them understand customer requirements.

The researchers concluded that the greatest difference between entrepreneurs and corporate managers lies in the difference of a single belief about the future. Professional managers assume the future can be predicted; they create goals and plans and then attempt to control how things will unfold. The fundamental assumption, therefore, is that personal assumptions and learning happens primarily in the beginning of the process. Serial entrepreneurs, on the other hand, find ways to use external inputs of all types to challenge their assumptions throughout the journey to their breakthroughs. They use a multitude of small steps and activities to help them adapt and and modify their goals and strategies.

Leading disruptive innovation requires a mindset of continuous adaptation. Going after big opportunities doesn’t mean we must bet the farm. Leading disruptive innovation involves determining which small steps will have the greatest impact. While taking this approach can indeed help minimize risk, it requires leaders to approach “planning” in a flexible way that allows for major shifts in goals, metrics, and timelines.

Persist – Take the surprise out of failure

When Sarah Robb O’Hagan, President of Gatorade, learned that many young football players pack bananas in their sport bags but find them mashed between their cleats before practice, she asked her product development team to develop a pre-workout drink pouch packed with carbohydrates. Gatorade launched the pouch with the goal of tapping into a white-space opportunity.

“We knew drink bottles like the backs of our hands, but pouches were a completely new animal,” according to O’Hagan. But while the pouches tested well in the lab, some of them leaked on store shelves. In many companies, customer complaints would have halted the innovation in its tracks. Rather than run for cover, O’Hagan helped Gatorade “reframe failure” by emphasizing the importance of trial and error. “We could have waited another six months to ‘get it right, but we would have missed both the summer season and a great learning opportunity. In fact, the leaky pouches caused everyone to revisit their assumptions about the packaging, which led to an even better ergonomic design and superior packaging materials,” she told her team[x]. Leadership like O’Hagan’s characterizes the reframe required for disruptive innovation. While few leaders want failure, setbacks are a natural part of the process when leading disruptive innovation.

Leaders who face the fear of failure head on – and who help their teams and organizations do the same – are most prepared to use setbacks as springboards to success. A Harvard University study on the impact of fear on decision-making, for example, found that fear creates pessimism, which leads to risk-averse behavior. This same dynamic occurs on a widespread scale when the stock market falls and investors sell at the bottom to “get out” in order to regain a sense of certainty.

Leading for disruptive innovation involves creating “optimistic persistence” in order to combat fear, pessimism and the tendency to retrench back into the safety of the existing business model. Research from Columbia and Harvard Universities[xi] found that when people were asked to act assertively, they experienced a biological response consistent with feelings of being powerful. When compared to people who were asked to act passively, those who felt more powerful took greater risks when given the opportunity to gamble money.

Leading disruptive innovation involves taking action in the face of uncertainty, seeing results, learning from them, and modifying assumptions and behaviors based on these results. Even when the results are “negative,” the goal is to persist in using the insights gained from the experience. Such an approach creates a sense of progress where positive results can be celebrated and setbacks can be seen as learning opportunities. This mental model feeds optimism and inspires further action, which results in the type of optimistic persistence required to weather the tough times.

Seize – Make the journey part of the (surprising) destination

Canon recently launched the EOS 5D Mark II camera, targeting general photo enthusiasts. But something surprising happened within months of the launch. Professional videographers started using the point-and-shoot camera. With video quality equal to more specialized cameras used for television commercials, this less expensive alternative packed a big punch. To Canon’s own surprise, the Mark II had unexpectedly started disrupting the high-end professional video market. Canon is now developing cameras specifically designed for this industry – and disrupting the market in the process.

A whole basket of examples shows how companies begin with one focus and end up succeeding with another. Wrigley started out selling baking soda and soap. Giving away gum was a perk for customers who responded with such surprising delight that the company shifted its entire focus to chewing gum. YouTube began as a dating web site before becoming the de-facto standard for sharing videos on the web. Hasbro initially sold pencils and school supplies before stumbling upon an independent inventor who sold the company the rights to Mr. Potato Head.

The path to disruptive innovation is not always predictable or linear. For example, Jim Collins and Morten Hansen, authors of Great by Choice, discovered that “luck events” play a significant role in long-term business success[xii]. Leaders who capitalize on good luck, and who are best prepared for bad luck, achieve far superior results than their peers. Collins and Hansen’s research shows that leaders need to find comfort in uncertainty, but also be well prepared to respond to unanticipated events.

Most companies view uncertainty, and especially surprises, as things to prevent and avoid. Even positive surprises like Canon’s are simply seen as lucky happenstance, far from being connected to real strategy. The underlying assumption is that predictability and control are the cornerstones of leadership. No wonder every management book on Amazon with “surprise” in its title is about how to minimize the possibility of experiencing the dreaded phenomenon.

Leading disruptive innovation, however, is a process fundamentally laden with surprise, the core essence of uncertainty. Recognizing the potential power of surprise when we receive unexpected jolts to our strategies, plans, and assumptions, allows us to respond with purposeful agility – versus dismiss surprises as problems while concurrently disregarding the insights or messages they may contain.

Disruptive innovation requires Disrupting Leadership

More and more leaders and companies recognize that they must proactively disrupt, or risk being disrupted. But business-as-usual leadership, where big visions are followed by detailed roadmaps and action plans, do more than stifle disruptive innovation. They represent liabilities to success. Leading disruptive innovation involves adopting principles that fall outside the traditional training of managers and leaders.

New leadership competencies are required to navigate disruption. This means uncovering one’s deeper motivations to drive meaningful opportunities for others; pushing personal boundaries to challenge one’s own assumptions; taking steps into the unknown with the view that failure isn’t failure at all but rather a stepping stone to learning and progress; and tuning into surprises as a kind of portal for gaining new insights and uncovering opportunities. To lead disruptive innovation successfully requires that we disrupt the most fundamental mindsets and behaviors that have led us to our current success.

[i] Christensen, C. (2003), The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fall, Harper Paperbacks, New York.

[ii] Kaplan, S. (2012), Leapfrogging: Harness the Power of Surprise for Business Breakthroughs, Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco.

[iii] Hamel, Gary & Breen, Bill (2007). The Future of Management, Harvard Business School Press.

[iv] Kim, W. and Mauborgne, R. (2005), Blue Ocean Strategy, Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

[v] http://www.geekwire.com/2011/amazons-bezos-innovation (accessed June 20, 2012)

[vi] A. Dijksterhuis and L. F. Nordgren, “A Theory of Unconscious Thought,” Perspectives on Psychological Science 1 (2006): 95–109.

[vii] http://money.cnn.com/galleries/2008/fortune/0803/gallery.jobsqna.fortune/3.html (accessed June 20, 2012)

[viii] Maddux, William & Galinsky, Adam (2009). Cultural Borders and Mental Barriers:

The Relationship Between Living Abroad and Creativity, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Published by the American Psychological Association, Vol. 96, No. 5, 1047–1061

[ix] http://www.inc.com/magazine/20110201/how-great-entrepreneurs-think.html (accessed June 20, 2012)

[x] Kaplan, S. (2012), Leapfrogging: Harness the Power of Surprise for Business Breakthroughs, Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco.

[xi] D. R. Carney, A. J. C. Cuddy, and A. J. Yap, “Power Posing: Brief Nonverbal Displays Affect Neuroendocrine Levels and Risk Tolerance,” Psychological Science 21 (2010): 1–6.

[xii] Collins, J. and Hansen, M. (2011), Great by Choice: Uncertainty, Chaos, and Luck—Why Some Thrive Despite Them All, HarperCollins Publishers, New York.