When former McKinsey & Company partner Bill Matassoni joined the legendary firm in 1980, management consultants had an image problem. For example, while McKinsey was considered a preeminent market player at the time, it was positioned in artwork supporting a Fortune magazine feature as the largest pugilist in a crowded boxing ring.

Back then, most McKinsey employees were pleased with being seen as the industry’s biggest boxer. Matassoni was not. Instead of being seen as the beefiest thug on the block, he wanted the firm to be known for something unique.

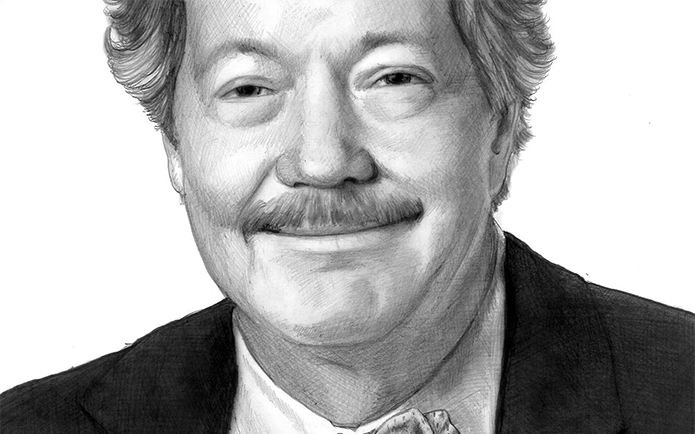

In his new memoir Marketing Saves the World, Matassoni offers insights from a 40-year career spanning McKinsey, BCG, Mitchell Madison and his own firm, The Glass House Group. In the excerpt below, he explains why he led the charge to free McKinsey’s reputation from the boxing ring and position the company as a leading producer of corporate leaders.

Marketing Saves the World Chapter 4: Creating the Leadership Factory

One Saturday morning, about two years after I joined McKinsey, I got a phone call from a man named Warren Cannon. He was the head of staff. Even though I reported to Ron Daniel, Warren was the guy I went to initially for advice. He was tough and very smart, and he seemed to like me.

“Bill, this is Warren.”

“Hi,” I said, wondering what could be important enough for Warren to call me on a weekend.

“I just wanted you to know you have been elected to the partnership of the firm.”

I was genuinely surprised. When I was approached by McKinsey, there was something said about my job being a partnership position and that it could happen as quickly as two years, but I had not broached the subject with anyone and no one had said anything to me.

I thanked Warren and said I knew he was the one who spearheaded my nomination. I didn’t know, but figured he did.

I thanked Warren and said I knew he was the one who spearheaded my nomination. I didn’t know, but figured he did.

“You have created quite a following. Lots of people had good things to say about you. Congratulations.”

I thanked him again and hung up. I sat there on an old wooden church pew I had bought from an antique shop in Connecticut, part of the decor in my barn-like loft on 38th and 6th. I thought to myself, not bad. From United Way football spots to partner at McKinsey in two years.

But there were ups and downs. Shortly after getting elected, I discovered I had a brain tumor. It was large, painful, but likely benign. It had to come out. In the morning, after nine hours of surgery, I awakened to find Fred Gluck at the foot of my bed. Shortly after, Ron Daniel joined us. Warren Cannon spent the entire nine hours with my family in the waiting room. Ron sent a note to the firm saying I was fine and “alert.” That was code for “he can still think.” Fred started introducing me as the McKinsey partner who had his brain removed. That’s when you know you belong, and I belonged at McKinsey.

How did this happen? Consider the following thoughts to be conjecture, but here’s my answer.

First, I got my personal strategy roughly right. Don’t hang around headquarters and lecture the partners about marketing—what little I knew. Pick a few of them to work with and make good things, new things, happen. I went out and embraced McKinsey and it hugged me back. Later I realized this was the right way to change the institutional image of a dispersed, international service firm—one person at a time. Remember the number theory where if you prove something is true for n and n plus 1, then it must be true for n plus 2? Moreover, I really did have a group of partners, many of them leaders of the firm, who trusted me and invited me to dinner at their homes in Paris, London, Tokyo, Frankfurt, Zurich, you name it.

Second, good things were ready to happen when I got there. The firm’s leaders had invested heavily in building McKinsey’s practices and intellectual capital. I showed up around harvest time. By luck, or foresight, I saw my role as pushing us away from academic theory toward issues that were important to senior managers. McKinsey certainly provided me with the ammunition to do that.

Third, BCG had scared McKinsey. BCG had good clients and good people around the world in countries where we thought we were dominant. Many of the partners felt a need for real change, not just more processes and frameworks.

Fourth, I fit the culture. I had the right educational background. I was in many ways naïve and I came from a poor background. Believe it or not, McKinsey in the early ’80s was led by partners who fit that profile. Fred Gluck grew up in a two-and-a-half-room apartment in Brooklyn with five brothers and sisters. His dad was a traveling salesman. In some ways, McKinsey people were superbly capable and, in other ways, not very savvy. That included me. Once, Ohmae and I were in Paris together when Leslie Stahl’s people called me. They wanted Ken to debate Boone Pickens, who was complaining that he was being prevented from sitting on boards in Japan. Ken said sure. I said sure. Pickens dominated the debate. It was very frustrating. But we got over it; failure was well tolerated at McKinsey.

Fifth, I didn’t fit the culture. I was not a good consultant or manager. I thought business was dull. I saw my role from the outside in, as a good marketer should, and tried to keep my partners honest about the quality of their thinking. I remember once Fred insisted that McKinsey had developed the idea of purchasing power parity. The next morning, I dumped a couple of articles on his desk that proved him wrong. My network outside McKinsey became as strong as the one inside. People like Adam Meyerson, Tim Ferguson, David Asman, Dan Henninger and Melanie Kirkpatrick at the Journal, Christopher Lorenz at the Financial Times, Steve Prokesch at Business Week, Steve Lohr at the New York Times and senior people at the Economist. I never asked them for favors and never sent them mediocre thinking. This network included my old friend Joe Browne, who had become an SVP at the NFL and Bruce Nelson, who would become vice chairman at Omnicom—two solid sources of advice on public relations and advertising.

Sixth, I really worked hard to understand the substance of McKinsey’s thinking and work even though I wasn’t advising clients. Early on, one of the senior partners, Carter Bales, gave me some good advice. He told me to read the 16 staff papers that summarized most of McKinsey’s thinking at the time about strategy and organization. I read them all carefully. I did the math. In fact, at Andover I won the math prize. I almost flunked accounting at HBS, but my quantitative skills held me up. I also read external material that I thought we needed to know. I dragged a copy of Robert Solomon’s book on the international monetary system to Cape Cod one summer and read it twice. Too many marketers, I suspect, don’t really get into the substance of what their companies do and how they deliver value.

Last, and certainly most importantly, Marvin Bower, McKinsey’s venerable founder, became my mentor. The first thing I did when I joined McKinsey was read Bower’s book Perspective on McKinsey. It was daunting. It made me think I was not good enough for McKinsey. In it, Bower explained why he wanted to create a management consulting firm that was as professional as a law firm. It was Bower who turned the firm around in the mid-’30s when James O. McKinsey died. It was Bower who, when he officially took over as managing partner in 1952, hired the first MBAs as consultants, believing that we would deliver more value with brains than experience. It was Bower who refused to fly first class. And most importantly, it was Marvin who insisted that McKinsey be a meritocracy.

We had a nice informal relationship. His office was close to mine. He had retired from active leadership of the firm and would wander in or I would go see him, sometimes on a specific topic or just as often to talk about the firm in general. McKinsey had hired an oral historian to interview at length some of the early senior partners who were getting pretty old. Marvin was one. I was asked to take over this project, both to guard it and use it appropriately. I read Marvin’s interview, which covered a couple hundred pages, carefully. So, we had things to talk about. He wasn’t in any way ostentatious and not much for entertaining, but I was a regular at his birthday parties.

I became genuinely fond of Marvin and felt that it was a privilege to work with him. He told me he had never seen an outsider understand McKinsey as quickly as I did. But he helped. He asked me not to use the words marketing and brand, and speak more about our reputation and relationship building. I followed his values and principles, and used them to guide what I was trying to do. I worked with senior people as well as junior people, regardless of their status, who had ideas and were well-intentioned. I put the interests of my external network ahead of ours, just as Marvin taught our consultants to do with their clients. Marvin policed McKinsey’s vocabulary and I tried to do the same thing. I didn’t let people talk about “solutions” or use acronyms to label their thinking. I took my role as keeper of the firm’s policies seriously. I reminded our teams they were never to mention client names. Nor were our clients allowed to mention us. These were important rules and I tried to make sure there was zero tolerance for any breaches.

Marvin kept my feet on the ground. I remember once I tried to write a policy on speaking engagements and when we should accept them. Kind of a bad idea to begin with. Sometimes common sense is better than a policy. In any case, I wrote a policy that basically said make sure the speaking opportunity is worth your time and McKinsey’s. I asked Marvin to look at it. He did and then he handed it back to me. He said, in a voice that got high and squeaky as he approached 80, “Bill this is fine. You make several good points, but maybe you should start by saying that when someone here is deciding to accept a speaking engagement, he should first ask himself if he has anything worthwhile to say.” Yes, I felt pretty stupid.

I learned a lot from Marvin and he helped me become a good partner. Sometime in his 80s, I think, Marvin lost his wife of many years, Helen. Not long after, he married a good friend of theirs who lived near them in Bronxville. His new wife Cleo and he bought a place in Florida and started spending time there. Then she died and Marvin was all alone. He started working on a book and would send me chapters. I read them and worried. His previous books were rigorous and structured. But I could find no structure or purpose in what he was now writing. Nevertheless, I kept reading the chapters and their iterations, hoping that they would eventually add up. But they didn’t. Finally, he sent me the whole book and asked for a full assessment. This was not something I could do over the phone. I flew down to see him. He met me and we had dinner. Then he walked me back to a guest room in the facility where he was then living. I sat down on the small bed and he on a chair and I told him I did not think he should publish his book, that it wasn’t up to his standards. I also told him he could submit it to Harvard Press and they would probably publish it because he was the author. He thanked me. The next morning, we had breakfast before I flew back to New York. We did not talk about the book and he never brought it up again. Some days, I think I did what was best for him; other days, I fear that I let my friend down.

So, the main reason I said to Ron Daniel that we should not be content being the biggest thug in a ring of thugs was Marvin. He wanted to create a profession of management consulting, a respected profession. Even though the Fortune article made the partners feel good, it wasn’t good enough. We needed to change McKinsey’s aspiration to be the “preeminent strategy consultant.” Michael Porter said many smart things, but maybe the smartest was, “Don’t aspire to be the best or the biggest; aspire to be unique.”

I followed my usual plan, wandering and wondering around, asking the partners, now my partners, what makes McKinsey unique. Almost all the answers were the same: “McKinsey is the preeminent strategy consultant.” Tom Peters agreed that it was the right question, but didn’t have an answer. However, Carter Bales did. Carter was a senior partner in the New York office. Among other things, he led McKinsey’s recruiting efforts at business schools. When I asked Carter my question, he said, “That’s easy. We are a leadership factory.”

“We are a what?”

“A leadership factory. We produce leaders. We produce more CEOs than any other institution.”

“The repositioning was valuable to us in several ways. Students now saw McKinsey as a next step rather than the end point in their careers. They did not need to make partner to succeed.”

Could this be true? I should have known that it might be. In my desk, I kept a handwritten list of all the McKinsey “alumni” who had left and become CEOs of major companies. Reporters were always asking for it. Sometimes I gave it to them, but I never typed it up. Call it preserving the mystique. The list got longer and longer. But what about this dimension of leadership? Did it make sense? Could it be a differentiating factor? More importantly, could it actually change the market-space we were in? I thought it could be much more than a product-market attribute. So did Carter and several others. It had the benefit of being true. We did produce lots of CEOs. And Marvin always insisted that when we consulted we served the CEO and not one of his division heads. That we took what he called an “integrated top-management perspective.” On the other hand, Bain and BCG tended to serve companies and even industries. So, was McKinsey essentially an elite group of future leaders serving leaders?

It seems obvious, doesn’t it? That leadership was part of McKinsey’s identity and value? But sometimes you are too close to see it or articulate it. Yes, we knew we were doing more than saving our clients’ money and helping them redirect their strategies. But more importantly, we were supporting and advancing the quality of leadership in the corporate sector both in the U.S. and other prospering economies. We needed to think about that idea and live up to it.

Once we discovered, or rediscovered, our strength, we needed to do something about it. In fact, we did three things. First, Carter and I changed McKinsey’s standard recruiting pitch. When we went to campus, Carter made it very clear that no one was to talk about making partner. That happened for only one in eight people who joined McKinsey and it took several years. Instead, we talked about joining McKinsey to finish off your preparation to lead companies. BCG and Bain and other strategy consultants couldn’t say that. They didn’t have our history or orientation.

Second, we beefed up our placement capabilities. I had been asked to run alumni relations when I arrived, but I did not do much. In general, people were treated well when they left McKinsey so we made modest efforts to stay in touch with them and help them stay in touch with each other. But we began to make improvements in our systems so that when people left, they had several job offers rather than one or two. In general, the positions they were offered were in senior management ranks.

Third, I continued to raise the bar on our external communications. While we still published articles about management in the Harvard Business Review, we focused more of our attention on issues that were affected by policy and international competition. In addition to Ohmae, Sawhill and Bryan, other practice leaders and individuals joined our efforts to own issues. On the other hand, we basically gave away our management ideas rather than treat them as if they were secret formulae. What, after all, do consultants offer? Three things: people, skills and knowledge. McKinsey did not offer solve-the-problem methodologies as our competitors did. Instead, our editorials on issues that mattered to senior management positioned us as leaders, not consultants.

The repositioning was valuable to us in several ways. Students now saw McKinsey as a next step rather than the end point in their careers. They did not need to make partner to succeed. If it happened, it happened. Clients saw our young consultants as leaders in waiting and were more willing to pay for their time. And institutions, semi-public and public, not well known to us made overtures of various kinds because they saw us as an influential network. Eventually, we formed the McKinsey Global Institute. Its work, which married macro- and micro-economic analysis, greatly enhanced and extended McKinsey’s reputation. It was a powerful change in our identity, this new dimension. We were seen differently and we saw ourselves differently.

I describe all this many years after it occurred. Hindsight is an exact science. I’m sure we did not put these efforts on paper as a tri-partite plan. But they did fit together. Two years after the cover story in Fortune that featured McKinsey in the boxing ring, another cover story about us appeared. Its headline was, “Who Produces the Most CEOs, GE or McKinsey?” I don’t remember who won. And it didn’t matter. This time, McKinsey was in the ranks of the world’s most admired companies: GE, IBM, 3M, P&G, etc. We had jumped out of the ring of thugs.

Was Marvin pleased? Had Carter and I, and the others who helped execute our plan, effectively told the world McKinsey was a unique professional institution? I think so. I hope so. Professions start and end with the quality of the people in their ranks. We had positioned McKinsey as an organization that starts and ends with leaders.

I want to pick up two points in the next chapter. First, the market-space is malleable. You can change it dramatically by reconceiving its dimensions. Sure, consulting is about process and results, but it can be about other things too—other things that not only differentiate and put you at the top of the pack, but put you into a whole new pack. Good marketers think hard and creatively about what those dimensions might be and how they can use them to bend the space and to bend it to their advantage.

Second, to actually change the perspective and position of your firm, whether you consult or make soda pop, you probably need to do three or four things that somehow add up to a coordinated and sustained effort. Doing just one thing probably won’t be enough. McKinsey needed to do more than change its recruiting pitch. But doing several things isn’t going to work either. You see many companies today try to change their image by adopting a new theme of the week: sustainability, diversity, convenience, nutrition, opulence, organic. Don’t be a chameleon. Identify new dimensions of value and then do things to substantiate your claim to be uniquely good in this new space.

For sample chapters of Marketing Saves the World and complimentary episodes of The Bill Matassoni Show, a documentary series expanding on concepts in Matassoni’s memoir, visit www.marketingsavestheworld.com