Uncertainty can’t be eliminated from the business environment, but as this author points out, it can be managed by transforming it into planned uncertainty.

Evaluating country risks is a crucial exercise when choosing sites for international business, particularly if investment is to be undertaken. Certain risks can be managed through insurance, hedging and other types of financial planning, but other risks cannot be controlled through such financial mechanisms. Some of these latter risks may be measured in a risk-return analysis, with some countries’ risks requiring higher returns to justify the higher risks. The study of country risks is also necessary in order to develop alternative scenarios: Uncertainty may remain, but it can be transformed into planned uncertainty, with no surprises and with contingency plans in place.

Each corporation confronts a unique set of country risks. As a result, this article does not prescribe a common formula. Rather, it discusses the many issues and analytical frameworks a business should examine as it develops its own evaluation of country risks and creates its own strategy to manage the uncertainties those risks entail. Fortunately, a great deal of relevant information is available on the Internet, and this article points to a number of helpful Web sites.

POLITICAL RISKS

POLITICAL RISKS

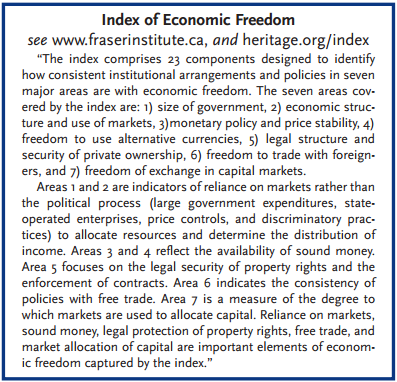

Prior to the 1990s, the political risks associated with interventionist governments were considerable. They included government expropriation, regulations that imposed inefficiencies, and foreign-investment restrictions. Many countries pursued the goal of economic self-sufficiency through extensive tariff and non-tariff barriers to both trade and investment. Bribery often influenced government decisions. In many countries today, such political risk has been reduced and replaced by a new acceptance of free markets and a belief that international trade and investment are the bases for economic growth. Nevertheless, political risks still remain. The Index of Economic Freedom ranks countries according to the impact that political intervention has on business decisions, while the Corruption Perception Index indicates the extent of corruption in each of 91 countries. To the degree that a government has the power to regulate and intervene in matters that affect businesses, bureaucrats may be tempted to provide the desired approvals in return for bribes. As a result, these indexes can be closely related.

The Index of Economic Freedom, which must be considered in a risk-return analysis, points to the various ways in which a government may take away potential profits. The Corruption Perception Index warns that doing business in certain countries will require clear corporate practices for bribery, ranging from enforcing a zero-bribery policy, to permitting specific types of “gifts,” to authorizing a local partner to undertake certain “assistance” activities for those in power. Canadian and U.S. legislation on foreign corrupt practices must be considered. Furthermore, new control and audit practices may have to be implemented to operate in a culture where corruption is common, and where employees may therefore not automatically adhere to the standards of honesty expected by the corporation.

For natural resource sectors, in particular, political risk may still be a showstopper, since the risk of nationalization, special taxes or new regulations is particularly severe. Managers in these sectors must consider whether the risks may be too high to justify investment. It remains helpful to seek the views of local political experts. One technique involves circulating a questionnaire to these experts, compiling the results, and returning them to the respondents for further commentary. This “Delphi” technique facilitates the development of a consensus view on the political risks that a potential investor faces.

Home-country political risks

Analyzing and managing political risks has become important even when doing business in one’s home country. It is not automatically true that country risks are greater abroad than they are in Canada. Inco’s experience with delays in its Voisey Bay project-the result of environmental objections, the advocacy of aboriginal rights and the issue of government taxes-has involved considerable difficulties compared with the relatively easy approval for mining projects in many less developed countries. When the question of Quebec’s secession is added to these political risks, many Canadian corporations may conclude that political risks in Canada exceed those in many other countries. In this respect, certain less-developed countries may offer a competitive advantage.

Managing political risks

International investment agreements attempt to limit political risks. Both Canada and the United States have signed investment agreements with many other countries that promise financial compensation for corporations based in Canada or the U.S. if their assets are expropriated. These agreements promise that the amount of compensation will be determined in a fair and just manner. Under NAFTA’s Chapter 11, corporations can sue a NAFTA government on the grounds that they have been denied “fair and equitable treatment” in a way that is tantamount to expropriation. However, it is not clear how far Chapter 11 or other investment agreements go in protecting corporations from new government regulations that increase costs or restrict prices. The Enron dilemma in India illustrates the potential seriousness of political risks.

Political risk insurance may be purchased as additional protection against specific outcomes such as capital repatriation difficulties, expropriation, or war and insurrection. Canada’s Export Development Corporation offers credit insurance for many such risks.

Economic risks

Economic risks may be particularly important in regard to exchange rates, economic volatility, industry structure and international competitiveness.

Exchange rate risks

In recent years, the risk of foreign exchange rate movements has become a

paramount consideration, as has the risk that a government may simply lack the economic capacity to repay its loans. Many countries have been experiencing ongoing fiscal deficits and rapid money-supply growth. Consequently, inflation rates remain high in these countries, and devaluation crises appear from time to time. A devaluation of one country’s exchange rate automatically creates pressure for devaluation in other countries’ exchange rates. Competitive domino devaluation pressures are intensified because of the reliance of many countries on primary product exports and their price volatility.

Recent crises—especially the Asian crisis of 1997, the Mexican devaluation of 1994, and the Russian crisis of 1998—have created a new risk of heightened foreign exchange volatility for some countries. Today exchange rates may be maintained at unrealistically high levels as a result of considerable inflows of foreign capital. Yet, these capital inflows may slow or even reverse abruptly. Foreign investors now recognize these risks of foreign exchange volatility. In the future, capital flows will be more sensitive to changes in each country’s financial system and general economic conditions than they have been in the past. Future surges in capital flows may translate into increased volatility of foreign exchange rates for some countries.

But how can foreign investors protect themselves from these exchange rate risks? Hedging mechanisms offer some hope for reducing foreign exchange risks, though generally not without some cost. Here are some other ways managers can cope with these country risks:

1. Consider the timing of your investments. Investors should restrict capital transfers to a country to those times when the foreign exchange rate is in equilibrium. The theory of “Purchasing Power Parity” provides a guide to likely exchange rate changes. Compare a country’s cumulative inflation over a number of years with the cumulative inflation rate of its major trade partners. If the difference in cumulative inflation rates exceeds the percentage change in the foreign exchange rate, then devaluation is a real possibility. For example, this calculation would suggest that the Mexican peso is currently substantially overvalued.

2. Borrow domestically to do business domestically and avoid foreign exchange rate exposure. Keep in mind that this approach does expose the business to the possibility of interest rate increases as a result of a central bank’s response to foreign exchange rate devaluation. For a foreign-owned financial institution, this approach also involves the possibility of a “run” on deposits, as the depositors seek to withdraw funds in order to transfer them abroad.

3. Focus on the devaluation risk when choosing among countries as investment sites. From this perspective, Chile is currently a less risky region for investment than Argentina or Mexico.

4. Consider the amount of capital required by those activities that are being developed in a country subject to devaluation risk. The significance of a foreign exchange risk may be relatively low for a business that requires little capital investment, like one in the service sector or fast-food industry; it may be high for a firm in the manufacturing and natural resource sectors, where considerable capital is required.

5. Spread the purchase price over as long a time period as possible. This allows domestic currency to be purchased at a lower cost if devaluation occurs. Alternatively, gear the purchase price to a weighted average of the exchange rate over future years, with projected future payments adjusted in accordance with the exchange rate.

Risks of economic volatility

Economic stability depends upon a strong banking sector; without it, a foreign exchange crisis may have a particularly severe impact. An ongoing challenge for financial institutions everywhere is that the time profile for liabilities is not the same as the one for assets. Banks borrow short-term from depositors and lend long-term. This exposes the banks to the risks that fixed assets may fall quickly in price and that depositors may make sudden withdrawals. With dramatic reductions in land and stock prices, bank loans made on the security of real estate and stocks suddenly may be at a major risk of default, further exacerbating the effects of a foreign exchange crisis, and transforming it into a general crisis in the economy.

Industry risks

Managers must analyze the domestic situation for industry risks such as the strength of competitors, the potential for substitutes, the capabilities of suppliers and customers, and the risk of new entrants. It may be helpful to determine the risk level by developing a matrix in which each industry risk is evaluated as minor, serious or “show-stopping,” and in which the various ways of mitigating each risk are analyzed. For many foreign corporations, one example of industry risk may be the difficulty in finding suppliers who can offer the required level of quality and service. Public utility disruptions may also be risky, especially for firms dealing in perishable commodities. (In some countries, for example, electricity outages are common.) For some Canadian corporations, one solution has been to encourage other Canadian or U.S. suppliers to open a business in the same locality. For others, the construction of one’s own utilities, such as power supply, is a solution to the risk of electricity outages. Such actions may serve to strengthen a corporation’s domestic competitive advantage. Further, the process of developing a matrix of industry risks leads to strategies and solutions unique to each country and, indeed, to regions within countries as well.

Competitiveness risks

It will always be necessary for managers to consider a country’s competitiveness factors when making investment decisions. For example, Latin American countries continue to rank poorly in international surveys of such factors; labour-intensive export facilities should likely be located in other regions of the world, despite Latin America’s lower wage levels. Findings in the World Competitiveness Yearbook provide some critical data on the competitiveness factors of 49 countries.

Intra-country economic risks

Managers would do well to consider risk differences within each country. Many countries contain a high-growth region with strong competitive attributes. For some industries, Mexico’s U.S. border region and Monterrey could be regarded as a part of the U.S. economy rather than the Mexican economy, since a major portion of trade and investment is cross-border.

LINKING POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC RISKS

In many countries, bank loans have been granted as favours to political leaders and their friends, often without due diligence. The 1997 Asian foreign exchange crisis revealed that a very high percentage of bank loans were non-performing. As a result, many Asian banks had a negative net worth and financial systems were in disarray. A democratic political system generally does not experience the spread of a foreign exchange crisis to its financial sector and its general economy, since politicians are accountable to the public. Both the opposition and the media bring bank loans that have been given for political affiliation to the public’s attention. For some countries, this has not been the case. Unless there is a basic shift in the political paradigm, such financial-sector disasters may occur again. Economic reform requires political reform.

The Asian economies may again become precarious if the difficult situation faced by China’s banks worsens, the result of large political loans to now-suffering state-owned enterprises. The development of alternative financial instruments could result in a reduction in deposits at domestic Chinese banks. Hence, the liberalization of the Chinese financial sector, combined with the growth of the stock exchange and the expansion of foreign banks, could lead to the collapse of the country’s domestic financial sector. Here, a change in the political system with new financial accountability for state-owned enterprises is necessary before a sound financial system can emerge.

Many commentators have argued that future growth in Japan and Korea will depend on the restructuring of corporate organizations, with a breakup of the conglomerates that have dominated many Asian economies. Only with such a dismantling of huge organizations will entrepreneurial initiative and innovation be released. Closing businesses that are suffering ongoing losses or even restructuring such businesses will require clearer lines of responsibility and ownership. Furthermore, bankruptcy laws will need to be rewritten in order to achieve such restructuring.

Changes in trade and investment agreements can substantially change the economic conditions under which a corporation operates. A notable example today is China’s entry into the WTO, which will require the country to cut its tariffs significantly and to eliminate many of its restrictions on foreign ownership. Foreign corporations that invested in China prior to WTO membership may suddenly face much less expensive import competition; those required to accept a joint venture partnership with a state-owned enterprise will face competition from new foreign wholly owned subsidiaries. In managing country risks that involve linkages among various political and economic forces, a particularly helpful Web site is the Economist Intelligence Unit. The site offers analyses of broad categories of risk as well as risk exposure associated with specific types of investment.

COUNTRY RISK STRATEGIES

For corporations that are searching for foreign suppliers and customers, as well as those that are evaluating investment opportunities, the analysis of country risks has attained a new importance and a new complexity. More careful differentiation among countries and business sectors is now required. For example, instead of viewing Southeast Asia as a group of tigers that have been involved in an economic miracle and subsequent downfall, it is now necessary to carefully analyze the situation that each individual country faces.

For corporations that are searching for foreign suppliers and customers, as well as those that are evaluating investment opportunities, the analysis of country risks has attained a new importance and a new complexity. More careful differentiation among countries and business sectors is now required. For example, instead of viewing Southeast Asia as a group of tigers that have been involved in an economic miracle and subsequent downfall, it is now necessary to carefully analyze the situation that each individual country faces.

Managers should prepare themselves accordingly, with an analysis of interest rates and stock prices, the country’s balance of payments, projections of probable macroeconomic policies, and fiscal and current-account deficits. It is important to examine alternative potential scenarios and projections, and assign probabilities to each scenario in order to determine the risks and rewards connected with particular business opportunities. PricewaterhouseCoopers has developed an index that indicates how one may quantify the impact of country risks in terms of equivalent tax rates and rates of return.

The events of September 11 and the subsequent conflicts have added another dimension to country risk. How to preserve the personal security of employees has gained new prominence in corporate strategies. Here, significant differences exist among countries, as some appear to be experiencing a heightened antipathy towards foreigners. Specific plans for protection and exit must be based on an analysis of each country.

The relative significance of various country risks differs from one corporation to another, depending on features such as the type of business activity, experience in managing a certain risk, and financial strength. Hence, each corporation has to develop its unique country risk strategies. In the context of globalization, the New Economy and the changing role of governments, the analysis and management of country risks is now of paramount importance.