The necessity for organizations to embrace “speaking up” is broader than “speaking truth to power,” although that is one manifestation. Speaking up is about improving group performance by engaging in open dialogue—across all levels of rank, position, and tenure—to ensure that organizations have all available knowledge when addressing challenging issues.

Unfortunately, open dialogue doesn’t always come naturally. People often refrain from speaking up and voicing new ideas to avoid contradicting a superior or embarrassing a colleague. Sometimes they remain silent because they don’t want to risk looking ignorant or coming across as a know-it-all. But while keeping quiet can work for self-protection, it does little for group problem solving and helping organizations avoid serious mistakes.

Consider the following three scenarios:

A human resources director receives a request from her boss to start a recruitment drive to staff a major upcoming project. Being closer to the relevant data, the director knows the company has suitable internal candidates available to fill the positions, but she tells herself, “You can’t tell your boss he’s wrong” and proceeds to initiate the requested recruitment drive.

An intelligence analyst team is ready to issue a report that concludes there is no sign of military build-up on an important border when a new team member sees evidence of the contrary. Eager to be a team player, the newbie assumes his teammates must know more than he does and does not raise his findings.

A hospital is struggling to contain an infection spreading across multiple wards. A nurse who has recently read about actions taken to reduce the spread of the same infection at another hospital keeps quiet, thinking, “I’m only a nurse, they aren’t likely to listen to me.”

For 15 years, I have worked with organizations to help their members share their knowledge, observations, questions, and concerns that could significantly influence critical outcomes. And based on my experience across industry, government, and academia, I can debunk two myths:

Myth 1: Speaking up is about having courage. It’s not. The individuals in our scenarios did not lack courage; they faced situational factors or norms that made them see speaking up as risky.

Myth 2: Only lower-level employees worry about speaking up. Wrong again. Unwillingness to speak up is pervasive across all organizations and levels—including the C-Suite.

The good news is it is possible for members of your organizations to embrace speaking up. This article explains how to achieve this by developing dialogue skills and increasing psychological safety while implementing teaming routines that provide the opportunity to speak up. It then highlights my work with the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) to illustrate the benefits of speaking up in a real-life setting. (The views expressed here are my own and do not reflect official DIA policy or the position of the U.S. government.)

Improving Organizational Dialogue

The basic dialogue skills that facilitate speaking up include:

- Test assumptions with others before accepting them as the only possible interpretation.

- Check your inferences about others’ behaviours and actions before assuming that you are correct and taking action based on your inferences.

- Share all the information relevant to the group solving a problem; avoid sharing only the information that supports your point of view.

- Provide concrete examples and data that support your position; allow others to determine if your evidence is persuasive.

- Explain the reasoning behind statements, questions, and actions to reduce the chance that others will misunderstand your intention.

- Advocate for your position or view; then encourage others to raise views that differ from yours and welcome questions about your views.

- When listening to others, don’t make assumptions. Ask questions to check that you have clearly understood their intentions and the reasoning that supports their ideas.

Although these dialogue skills may seem obvious, they are difficult to use in an everyday context without systematic learning in a safe environment. Self-protection is deeply embedded in speech patterns. Unlearning and then relearning ways to interact with greater openness and integrity takes time and effort.

New dialogue skills can be introduced in a workshop, but they are learned while interacting with a group you normally work with. In groups where these dialogue skills are commonplace, the need to withhold knowledge to protect oneself is significantly reduced. Dialogue skills encourage members to offer all the information available in the group, which increases effective problem-solving and the development of new knowledge.

Learning and practicing these dialogue skills may lead to greater vulnerability, where being wrong, misunderstanding, or realizing that another person’s idea makes more sense are likely outcomes. Therefore, team members need confidence that others will respond with curiosity and interest, rather than blame or disapproval. This leads to the second major component of speaking up—psychological safety.

Psychological Safety

Leadership expert Amy Edmondson defines psychological safety as “a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking… [team members have] a sense of confidence that others will not embarrass, reject or punish someone for speaking up.”

This implies that psychological safety is a group responsibility, rather than just an individual expectation, whether that group is a team, a division, or the entire organization. A leader cannot create a psychologically safe space alone; all members must act and react in ways that jointly create a space in which it is safe to speak up. It is possible to create psychological safety within a team or unit, however, even when the larger organizational culture has not changed.

“One of the ironies of speaking up is that, to the individual who makes the choice to withhold his or her knowledge in a meeting, that small act might seems insignificant. Yet, when such choices are repeatedly made in hundreds of meetings across an organization, the loss of knowledge significantly reduces the organization’s ability to act effectively.”

Psychological safety is not the same as group cohesiveness, which research has shown can reduce the willingness to disagree with others. Psychological safety is also more than interpersonal trust, which is based on shared interests or belonging to a group. Trust remains fragile; a misunderstanding or mistake can easily destroy it. By contrast, psychological safety can withstand mistakes and misunderstandings. Indeed, psychological safety provides an environment that encourages challenge and disagreement, because thoroughly exploring different perspectives can lead to greater understanding and increased knowledge.

Psychological safety grows gradually through repeated interactions over time and through reflective conversations. It is based on three conditions: experiencing others’ capability to perform specific tasks, the reliability of others to perform the agreed-upon tasks, and witnessing the integrity and kindness of others in the work situation.

These three conditions are best met by group members periodically spending time together face-to-face and gaining the opportunity to speak up, which leads us to the third component—teaming routines.

Implement Teaming Routines to Encourage Speaking Up

Tiona Zuzul and Amy Edmondson studied the Lake Nona project in 2016 to explore the way leaders enable group members to coordinate, collaborate, and innovate within a project. The Lake Nona project was a mega-project in the built environment, a US$2 billion medical and research campus and residential community. It encompassed a “7,000-acre residential and research cluster that would be developed by hundreds of collaborators from diverse organizations, professions, and industries to build a community with both a high quality of life and environmentally sustainable buildings and infrastructure.”

The researchers found that the leaders of the project had created multiple ways to bring groups together in conversation that enabled coordination and collaboration. The researchers labelled these interactions as “teaming routines.” Examples of a few of the many teaming routines they identified included two-hour quarterly dinners, where the leaders of the many organizations came together to share stories about their families and personal lives; thematic council meetings, where individuals involved in particular functions came together; other meetings, where individuals from different groups came together to brainstorm ideas and then went away to test those ideas and then came back again to refine and improve them; and project leader dinners, held every two months to share progress and solicit feedback from one another.

I have borrowed Edmondson’s term and used it here to denote regularly held meetings among a team or group that provide the opportunity for the exchange of ideas, the co-creation of ideas, and coordination, in the interest of accomplishing the group task. By including teaming routines in the three components needed for speaking up, I imply that even if members have gained skill in dialogue, without the opportunity to interact with colleagues about the issues they jointly face, the skills cannot enhance the likelihood of speaking up.

When organizations make changes to become more team-based or to create greater collaboration, many practices that supported the previous hierarchical structure are often still in place. These practices may have become so familiar that they are no longer in conscious awareness. They have become just the way we do things around here; yet, they can prevent speaking up. Teaming routines that support speaking up achieve the three key objectives detailed below.

Teaming routines create opportunities for members to meet and exchange ideas. Collaboration and problem-solving between members does not happen automatically. It has to be a conscious decision on the part of everyone involved to spend time periodically talking about things that matter to the long-term success of the group. Through such interactions, individuals develop transactive memory; that is, knowledge of what others know, which increases respect for and interest in the ideas of others. Teaming routines establish times and venues to bring people together. There are various activities that can achieve this, such as: Hold reflection meetings following an initiative to figure out what went well and what could have gone better. Involve team members in decisions that affect the unit. Hold social gatherings of members to build and strengthen relationships, such as dinners, outings, and athletic events. Hold problem-solving meetings about difficult issues the group is facing. Regularly conduct brief stand-up meetings to keep apprised of what other members are working on.

Teaming routines create a setting conducive to conversation. The physical setting in which groups talk has an impact on who talks and who remains silent, as does the size of the group. Reconfiguring the space and size frees members from being trapped by existing behavioural cues. The change disrupts the previous pattern and allows a new pattern to form. Teaming routines that make the setting conducive to conversation include several key activities. Hold meetings at a round table or in a circle of chairs, instead of at a rectangular table, as a visible symbol of the equality of ideas. Relinquish the power of the pen to a member to take notes on a flip chart. Have members discuss a topic in small groups of three or four before bringing their ideas to the larger group.

Teaming routines reduce the visible signs of the power difference. The power difference between members and the leader is one of the greatest deterrents to members speaking up. Hierarchy inhibits voice. A leader can encourage or discourage conversation with the use of dress, actions, and comments, such as: The leader wearing the same level of attire as the participants. The leader sitting with the group, rather than standing upfront. The leader allowing members to respond to one another, rather than feeling the need to comment after each member has spoken. The leader making sure everyone is heard by using a round-robin format to allow all members the opportunity to offer their ideas in turn.

These are only a few teaming routines that encourage speaking up. There is a multitude of such routines, large and small, that can make a difference. Implementing such teaming routines, increasing psychological safety, and developing dialogue skills can help solve difficult problems in any organization. To illustrate the benefits of speaking up in a real-life setting, I have prepared a detailed summary of my work with the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA).

Practices and Norms at the DIA

The DIA is one of 16 intelligence agencies in the United States. The agency provides assessments of foreign military intentions and capabilities to U.S. military commanders. The agency’s analysis informs U.S. policy, defence strategy, weapons development, weapons acquisition, and military planning. I believe that my experience with the DIA will resonate with firms that view knowledge as their principal product in today’s global marketplace.

Over a period of three years, I worked with 15 different teams at the DIA to help team members learn to speak up. These groups spanned the organization from working-level to executive ranks and included a cross-section of DIA offices. They represented both intact units and temporary, purpose-created teams. The common thread for each group was the need to openly share ideas and expertise across the team to co-create knowledge that would best serve the DIA’s customers.

Because of the DIA’s traditional hierarchical structure, its processes and practices reinforced information flow that moved up and down the leadership pyramid, usually with multiple gatekeepers along the way. When threats and customer needs changed in the post-9/11 world, the DIA had to shift from a competitive, transactional, single-expert intelligence analysis and production model to a highly collaborative paradigm that featured the co-creation of knowledge from the “bottom up” by analysts representing diverse disciplines and many organizations.

Quality control was an important issue at the DIA; after all, mistakes could cost lives. But it became clear that existing quality-control processes and embedded discourse practices were chilling the desired environment that demanded the respectful exploration of assumptions, the challenging of ideas, and multi-voiced collaborative knowledge co-creation. For example, the intelligence review processes for written reports and oral presentations (out-briefs) greatly discouraged analysts from speaking up. Reviewers, whose job was to maintain quality, took their role very seriously (lives were at stake) and tended to interpret any questioning of their critique as a challenge.

Analysts found themselves increasingly reluctant to advocate strongly for their findings for fear of angering the reviewers, who could have a negative impact on their careers. However, if analysts did not present a strong defence of their or the team’s findings, the senior analysts often viewed it as proof of their or the analytic team’s inexperience. Sadly, when analysts failed to explain their thinking fully or to advocate strongly for their conclusions, senior analysts were unable to learn from the new thinking that subordinates were charged with bringing to the DIA. So, despite its good intentions to produce a quality product, the DIA’s analytic review process worked to prevent speaking up and thereby limited the ability of the generals to obtain the knowledge they needed to make decisions and for team members to improve their processes.

Norms within analytic teams also discouraged speaking up. For example, typically, the team leader of a newly formed team would immediately deconstruct any analytic task into component parts and assign each part to expert analysts, who might be scattered across the DIA buildings. When the component parts were completed, the team leader would assemble the report and then pass it among the contributors for critique and changes, a practice which provided only minimal opportunity for collaboration or for learning from one another. The team decision-making norms also discouraged speaking up. If a member was absent when a decision was made, the norm was for the team member to accept and support the decision without going back over it to question the logic on which it was based. Both norms, as well as many other examples, prevented analyst teams from making use of all the knowledge they had, and from speaking up.

Psychological Safety at the DIA

As the practices and norms above illustrate, on many occasions, the environment did not feel safe for analysts to speak up, either within their team or with superiors. DIA analysts believed that they were facing several risks. They were concerned about being viewed as not a team player. The only options they saw were rolling over or being insubordinate. They felt that repeated attempts to help the other person understand would only anger them. They saw it as occupational suicide to offer a different way to handle an assigned request. They were reluctant to reveal their concerns about a task, once having agreed to do it.

Dialogue Skills at the DIA

The DIA leadership saw improving dialogue skills as a way to address the issue of analysts’ failing to challenge assumptions and as a way to reduce groupthink. The dialogue workshops for each team consisted of three workshop days that were spread over three months. Between meetings, team members practiced the skills during their regular team interactions. The workshops were tailored to the DIA, by asking workshop participants in advance of each workshop session to write out a case—an actual conversation—that had not gone as well as they had wished.

During the workshop, participants, working in small groups, read and discussed each other’s cases and offered suggestions to improve their conversations. Over time, participants began to realize that, although they were blind to examples in their own cases of when they were withholding knowledge to protect themselves, those examples were obvious to other members. By sharing vulnerabilities and mistakes in their conversational cases, participants recognized that no one was immune to such incidences and that by helping one another they would all become better at using the skills. More importantly, they realized that, as a team, they would be more effective in their analytic work.

The workshop discussion of these conversations had a profound impact on the sense of psychological safety within the group. Team members came to understand that in situations where they felt threatened or embarrassed, they had been acting in ways to protect themselves. And they realized that their actions also limited the sharing of knowledge as well as the ability to learn from others within the team.

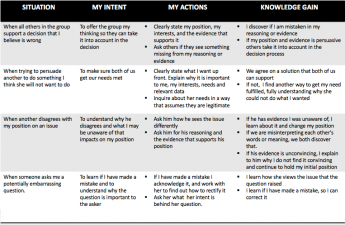

In reviewing over 300 cases, I was able to identify patterns in the dialogue between team members within the DIA that limited their individual effectiveness as well as the effectiveness of their teams to generate needed knowledge. The table below illustrates a few of those patterns that were present across many analytic teams:

In the table, the first column identifies some of the difficult situations in which analysts found themselves. Column two explains the intention of analysts; that is, what the analysts tried to do when they found themselves in those situations. I note that their intentions were never malicious; rather, they were attempts to avoid embarrassment or to prevent others from holding negative views of them. Column three shows the actions that analysts took to carry out their intentions. The last column lists the team’s or individual’s loss of knowledge from those actions, which had an adverse impact on the team’s outcomes. One such incident seems unimportant, but if multiplied day after day, and in team after team, the combined loss of knowledge is enormous, as are the potential mistakes made by the agency.

The Fresh Look Team

To address these concerns, I worked with Adrian Wolfberg, the director of DIA’s Knowledge Lab, to build greater collaboration among the analyst team members and to develop team members’ dialogue skills that would enable them to speak up. One of many teams we worked with was designated as Fresh Look. This was the project name for a team that was put together to address an analytic challenge that several previous teams had attempted and failed to solve. The Fresh Look team was co-located in a space newly designed for collaboration and was provided with the latest analytic technology. They worked on the analytic challenge over a period of three months. At the same time, they were developing the dialogue skills that would eliminate the issues noted in the table above, which were impeding speaking up.

In the Fresh Look example, which is described in more detail below, I primarily focus on the changes that occurred within the team. However, the team also needed to prepare to speak up to DIA leaders to present its findings. The dialogue skills were a critical element in that preparation, but ensuring psychological safety, external to the team, was also necessary.

External psychological safety was addressed in two ways: 1) by having the DIA’s third-most senior executive, the chief of staff, provide the charge to the Fresh Look team, making clear his support; and 2) by having Wolfberg, the director of the Knowledge Lab, provide the team with ongoing situational awareness and understanding of senior staff concerns.

The chief of staff introduced the challenge at a meeting of the Fresh Look team, explaining that the team was charged with not just duplicating the existing quality-control process. Team members needed to tell leadership how analysis should be done. He told them to create their own goals, and their own strategies to accomplish those goals, and to design their own project out-brief. The challenge to Fresh Look, then, was twofold: solve the analytic challenge, and do it in a way that helped the DIA improve its practices so that analysts would be better able to move knowledge up through the chain of command. As the team began its work, it was clear that many members were uncomfortable with such loose direction. Only gradually was the team able to create its own goals and strategies. However, by the end of the three months allotted for the project, the team members had created new ways of working and were able to speak up with each other with increasing frequency.

The first major change the team made occurred four weeks into the project. At a Friday meeting, with two of the team members absent, the others decided to organize their work into several smaller teams, similar to the standard DIA routine, each devoted to a piece of the larger question described earlier. On the following Monday, at the morning meeting, the two missing team members were back in place. They challenged both norms. They asked the rest of the team to go over their logic for reaching the decisions they had made on Friday. Instead of rebuking the two, the team not only laid out their logic but also reopened the idea of how to get the team’s work done. The Friday team members acknowledged that their decision had likely been driven by being tired by the end of the week and wanting to get to a decision so they could leave work and start the weekend.

The willingness of team members to challenge and be challenged had begun to develop within the team during the previous weeks. They had begun to recognize the damaging conversational tactics that they had been using and had started pointing them out to one another. Those nascent dialogue skills were now being exercised in an important team decision.

The group’s reaction to being challenged (about revisiting a decision and how the work was divided into component parts) reinforced their sense of psychological safety, encouraging yet another team member to raise a much more critical assumption that had been troubling her—how the team had framed the analysis question. Her position was that the way the analysis question was framed was too restricted. The group then engaged in an honest and open dialogue about the analysis. As a result, the team significantly broadened the scope of its analysis. This reframing of the question eventually led the team to discover a remarkable finding: the intelligence community had not been collecting information that could prove or disprove the reframed question, leaving it blind on a critical issue.

The next table illustrates the changes in dialogue skills that developed within the Fresh Look team over the three-month period:

In the first column, the situations mirror those of the previous table because such situations are a normal part of group life. What is different in this table is the intent (second column), which is focused on gaining knowledge, rather than on winning or saving embarrassment. The actions, in the third column, follow from that intent, in that team members seek to understand others’ points of view and to strongly advocate for their own perspective, while staying open to the idea that they may not yet have all the information. The last column illustrates the way the dialogue skills increased the knowledge gained by the team.

For the Fresh Look team, holding a different intent (as seen in the second column) significantly improved the members’ ability to work together. It enabled them to more efficiently exchange and integrate their disparate information and to begin to think about and articulate what the interactions among these various disciplines/systems might mean for their customers. While co-creating the final product, team members were able to learn what the others knew and needed to know (transactive memories), enabling a process of co-creating knowledge from the bottom up. The team’s interaction provided a model for the collaborative co-creation of the new, fused, holistic knowledge that would be the hallmark of future analytic team products.

At the end of the Fresh Look project, the team briefed high-level DIA staff on the findings, somewhat analogous to the out-brief described earlier. However, the Fresh Look team redesigned the meeting format, as well as the seating arrangement of the room, to promote mutual learning, rather than the typical presentation and critique. The team arranged for the leaders and the Fresh Look team members to sit together around a table, rather than having a presenter at a podium. The setting indicated the team’s intent to have a dialogue, as well as promoting a sense of equality, even though the analysts would be in conversation with the DIA’s most senior leaders.

The team members also staged the content presentation differently. Instead of just reporting a this-is-what-we-found report, they told stories about how they navigated the subject matter and how they overcame challenges during the journey. The format allowed the senior leaders to see how the team arrived at its conclusions. Designated team members gave short factual presentations and offered their perspective. The out-brief then became a conversation. In the course of the conversation, Fresh Look team members were able to strongly advocate the findings they had developed and to demonstrate their openness to the views of the senior leaders.

The team was particularly proud of its interaction with one senior executive. At the out-brief, an executive reacted with surprise that the team did not know about the existence of a critical piece of information, stating that everyone knows it exists! The Fresh Look team members quickly recognized the emotionally charged challenge and worked to avoid an emotional trap that could have deflated and side-tracked them away from the issues. The team indicated that they respectfully disagreed with the executive, and then laid out the process they had gone through to find the data, describing what was made available to them and what had been hidden from even the most senior team analyst who specialized in the issue.

This detailed explanation led to a more general discussion of how information is shared and accessed at the DIA, which brought new insights to the senior executives that were present. Drawing on its dialogue skills, the team moved the meeting from a familiar defensive exercise to the development of knowledge. It became apparent to the executives in attendance that the quality of the team’s findings and the skills exhibited by the team members in being able to detect and overcome dysfunctional norms with both respect and transparency was a thunderous testament to their ability to speak up, even in a high-stakes situation with senior management. Out-briefs from Fresh Look, and from every team after that, noted that team members finally understood what it meant to collaborate—to co-create knowledge.

The Fresh Look example illustrates the three components that facilitate speaking up, which I mentioned earlier in this article: dialogue skills, psychological safety, and teaming routines. The example also illustrates how the three components are intertwined. Each component affects, and is affected by, the others. The process creates a virtuous cycle, as illustrated visually in the following diagram:

The Fresh Look team members became proficient in dialogue skills by practicing what they had learned during the workshop that spanned several weeks. The workshop days were designed to provide a psychologically safe environment in which members could uncover the dysfunctional tactics they had been using and practice new ways of interacting. As team members became more skillful at speaking openly and honestly with one another, the authenticity of their interaction further increased the sense of psychological safety within the group. By using their dialogue skills to challenge longstanding dysfunctional practices and norms, such as through dividing a problem into parts, team members were able to build teaming routines that were more collaborative. For example, they changed the format of the out-brief and were able to co-produce more comprehensive and insightful analysis.

One of those decisions (e.g., to work collaboratively instead of dividing up their work) led to the establishment of an interaction routine that provided consistent opportunities for members to learn what the individual team members knew and what they needed to know. The process helped to build their transactive memory, which acted to increase the sense of psychological safety in the meetings. Likewise, psychological safety increased the ability of the team to speak authentically during teaming routines, as illustrated by a member taking a risk to voice her opinion that the way the group had framed the challenge was too restricted.

The new teaming routines created the opportunity to practice and deepen the team’s dialogue skills. The interaction of the three components enabled members to challenge each other’s assumptions and incorporate each other’s ideas—in other words, to speak up. Speaking up increased the co-creation of insightful knowledge products and the ability of the team to present and effectively defend its findings in the face of sharp, senior-level critique—so, speaking truth to power.

How Your Organization Can Benefit from Speaking Up

The knowledge that organizations need in order to effectively address their most challenging issues resides within the organizations, but is often unavailable because members find it too risky to speak up. The problem of members withholding their knowledge is far more complex than the solutions that are frequently offered by management, such as training programs or an edict to speak out. A viable solution to increase the availability of knowledge requires concurrent changes in three key components: dialogue skills, psychological safety, and teaming routines.

Learning dialogue skills requires practice in a real setting, where it is possible to address real issues. The process is most effective when team members and the team leader learn the skills together. Dialogue skills allow members to learn what others know and need to know, creating transactive memories and enabling the process of co-creating knowledge.

Organizations may have practices in place that are vestiges of previous eras, but that have become so familiar that they are implemented almost automatically. As organizations move toward greater collaboration and teamwork, a review of legacy practices and norms can ensure that those vestiges don’t unwittingly undermine today’s knowledge-sharing goals.

One of the ironies of speaking up is that, to the individual who makes the choice to withhold his or her knowledge in a meeting, that small act might seems insignificant. Yet, when such choices are repeatedly made in hundreds of meetings across an organization, the loss of knowledge significantly reduces the organization’s ability to act effectively. When an organization’s members have dialogue skills, feel psychologically safe, and work in a group where teaming routines support speaking up, needless mistakes are avoided, time is saved, and knowledge is available with which to make informed decisions.

[1] Amy Edmondson, “Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams,” Administrative Science Quarterly 44, no. 2 (1999): 350–383.

[2] Tiona Zuzul and Amy Edmondson, “Team Routines in Complex Innovation Projects,” in Jennifer Howard-Grenville, Claus Rerup, Ann Langley, and Haridimos Tsoukas (eds.), Organizational Routines: How They Are Created, Maintained, and Changed (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2016), 179–202.

[3] This view of their role corresponds to the early ideas of quality-control inspectors in manufacturing settings where initially quality was viewed as catching errors versus the later and more useful reframing of the role as helping to design a more effective process that resulted in quality improvement.