The COVID-19 outbreak offered businesses around the world a simple choice: adapt or die. Some organizations responded by engaging in digital transformation, while others focused on performing a social role by embracing charity, philanthropy, and other community-based activities. Results have understandably been mixed, and not just because of the unprecedented nature of the disruption created by the pandemic.

Simply put, the traditional tools of crisis management are not enough to maximize a firm’s chances of survival in today’s chaotic environment, which calls for a more holistic strategy. Indeed, in order to overcome the significant challenges introduced by COVID-19 and light up opportunities hidden in the outbreak’s dark tunnel, firms need to embark on a born-again journey of self-discovery and healing similar to the mental health recovery process. This involves accepting the need to engage in a grieving process that shapes a new raison d’être for the firm after rejecting traditional thinking and redefining business practices across the organization.

The conceptualization of deploying a business recovery process to develop a new, sustainable, and profitable business model in response to a crisis follows Albert Bandura’s social cognitive theory of human agency, which states that people are agents of their experience and not merely passive respondents to a deterministic environment or automatons driven by neurocognitive processes. Following this logic, firms should engage in a recovery process to proactively face any form of major disruption (digital, environmental, organizational, social, or viral). But deploying a recovery strategy in the corporate world, especially during a pandemic, requires clarity regarding its definition, not to mention how corporate managers should implement the process.

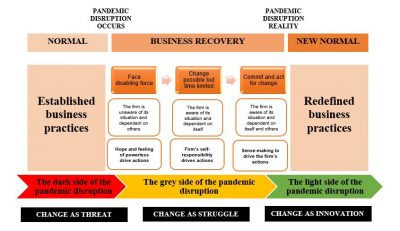

Based on my research and consulting work with clients across numerous industries, this article outlines the logic and stages of the Business Recovery Strategy Framework (see below, and explains how it can help managers organize their thinking and plan innovation while enabling them to adapt their organizations to the emerging behaviours and trends that represent the “new normal.”

Exhibit 1: Business Recovery Strategy Applied to Pandemic Disruption

Battling Inertia and Nostalgia

One of the most commonly accepted realities of business is also one of the most ironic: successful firms with established business practices fail to adapt to unexpected changes in the market. As a result, these companies can experience a tough or easy recovery process depending on their ability to disengage from established organizational and business practices. Disengaging from a firm’s so-called best practices, of course, isn’t easy, since managers associate them with positive outcomes. But this association is based upon previous experiences, and when conditions change, previous best practices may no longer be a suitable driver of success. In fact, when facing a disruption, making decisions based on established best practices can be extremely costly.

Why do managers stick with established modes of thinking when dealing with the unexpected? Blame a combination of corporate inertia and nostalgia.

When facing a fluid external environment, these two factors lead many firms to consider internal change an additional threat. This, in turn, blocks the development of new modes of thinking or actions that can open the door to innovations and dramatically improve competitiveness in a new environment.

In business circles, being blinded by inertia and nostalgia when a disruptive force exposes an opportunity is often described as having a “Kodak moment.” Managers of Eastman Kodak—which filed for bankruptcy in 2012—infamously failed to disengage from established modes of thinking as they oversaw the invention of a technology that led to the company’s demise as an industry leader. As a result, instead of revolutionizing the sector after developing the first digital camera, the company tried using the new technology as a prop to support its existing business model.

As Forbes contributor Chunka Mui noted in a 2012 article on the legendary corporate blunder, the choice “to use digital as a prop for the film business culminated in the 1996 introduction of the Advantix Preview film and camera system, which Kodak spent more than $500M to develop and launch. One of the key features of the Advantix system was that it allowed users to preview their shots and indicate how many prints they wanted. The Advantix Preview could do that because it was a digital camera. Yet it still used film and emphasized print because Kodak was in the photo film, chemical and paper business.”

“Simply put, Kodak managers couldn’t read the writing on the wall because they put products over customers in their thinking. And unfortunately, glorifying established practices is common when businesses face the need to change.”

With management thinking stuck in the past, the photography pioneer simply assumed consumers would want a digital camera that still required them to buy film and pay for prints. And as the company kept investing in its film division, competitors focused on the opportunities created by the industry’s disruption. In 2013, Kodak entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, emerging with a new focus on commercial printing.

Simply put, Kodak managers couldn’t read the writing on the wall because they put products over customers in their thinking. And unfortunately, glorifying established practices is common when businesses face the need to change. This is particularly true among CEOs of large B2B companies, where a mix of melancholy affection and convictions related to previous success prevent established companies from seeing a new context as a suitable period to undo their current business practices and modes of thinking, which are limiting their ability to strategically respond to disruptive forces. But it is a real problem for consumer-focused ventures as well.

Ultimately, corporate inertia and nostalgia will always lead to a loss of competitive advantage. Take, for example, the experience of small furniture businesses that have faced a perfect storm thanks to cheaper Chinese furniture, the advent of giant low-cost competitors such as IKEA, and 3D printing. This is an “adapt or die” situation. But many of these companies ironically, and firmly, believe that their previous path to success is part of their DNA even when that path is no longer profitable.

Whenever our normal is altered by a major disruption such as the current COVID-19 pandemic, fear and resistance are inevitable as we are hit with a flood of unanswered questions: Will the economy tank? Should our firm fire people? Should we cancel business and innovation projects? Can we develop better business practices than our pre-crisis practices? Is survival even possible?

This is a natural response. However, based on fear and resistance, this way of thinking tends to idealize pre-crisis situations. And as my academic research and years of consultancy work with small and large companies in multiple different sectors has shown, the “it-was-better-before mindset” doesn’t provide the foundation required for forming a relevant adaptation strategy that generates new business opportunities during a crisis. Instead, it leads to putting innovation on hold, which prevents the activation of a creative and proactive process that can expose new opportunities generated by changes in the market and competitive landscape.

Deploying a Business Recovery Strategy

Defining and implementing a business recovery strategy counters the natural inclination to idealize established business practices and modes of thinking when facing any major disruption, including a pandemic. But effectively deploying the framework to overcome inertia and nostalgia and emerge as an industry leader requires understanding that the process is a three-stage journey of self-discovery, reinvention, and goal setting that takes place in the context of a “new normal.”

STAGE ONE—Undergoing the disabling power of disruption: When first impacted by an event like the COVID-19 pandemic, firms are thrust into a state of unawareness, where they are suddenly dependent on others for context and ideas about how to react. At this stage, decision-making is driven by either hope or a feeling of powerlessness, while management strives to engage in actions that reduce employee stress and maintain stakeholder confidence. Measures taken often include policy changes affecting the entire organization or targeted departments such as human resources, sales, communications, and finance. A firm, for example, might move to enable employees to express their fears along with how the sudden disruption has affected their personal life and workplace productivity.

STAGE TWO—Change possible, but time limited: As a disrupted firm develops situational awareness, it becomes less dependent on external forces for context and ideas. In this stage of developing self-responsibility, management’s focus shifts toward exploring possibilities in the disruptive environment. During this “let’s-try-something” stage, interaction with employees can move beyond making sure everyone is coping as individuals by bringing employees from different departments together to creatively reflect on how to best move forward and manage three main priorities—clients, suppliers, and employees—in the new context. And by empowering employees to participate in the firm’s business recovery, management opens the door to creating a new sense of purpose across the entire organization.

STAGE THREE—Commit and act for change: Once aware of its situation and self-dependent, a firm can move to make logical changes that positively address—and even take advantage of—disruptions in both the workplace and market. After accepting the need to change and proactively engaging employees in the process, management exposes the light at the end of the pandemic tunnel by focusing on helping departments identify their new strengths and needs while redefining best practices for the new normal. During this stage, leadership generally knows what needs to happen and can express these needs to employees and external collaborators as they move to reinvent operations to thrive in the “new normal.”

Redefining Business Practices for a “New Normal”

The business world as we knew it just a few months ago will not survive the pandemic. But as tough as the coronavirus outbreak has been to manage, there is no question that the chaos created has presented businesses with an excellent opportunity to step back and reinvent themselves in ways that simply would not have been considered voluntarily under non-crisis conditions.

Indeed, thanks to COVID-19, it has never been easier to justify attacking deeply rooted convictions and established business practices.

But successfully navigating the business recovery process requires all concerned to like “the new me.” To help stakeholders appreciate the reinvented firm, managers should take the following actions to align key business practices with the new normal:

BUSINESS STRATEGY: When facing a “new normal,” a firm’s strategic review process should be demystified. Instead of being exclusively led by top managers, strategy development in times of major crisis should take a holistic and multidisciplinary approach.

ORGANIZATION: In a “new normal” context, firms should set up a committee charged with anticipating possible future disruption in order to maintain a readiness to quickly adapt to unexpected and dramatic changes in the competitive landscape or market conditions.

FINANCE: In a “new normal” situation, firms should engage in relevant cost reduction strategies while creatively sourcing the funding necessary to avoid cutting key employees and budgets.

HUMAN RESOURCES: When social distancing needs subside and reduce the need for remote working, employers should consider a hybrid path forward instead of a return to previous workplace practices. This path forward should be based on both the productivity results achieved during the pandemic period as well as the needs and feelings of employees.

CUSTOMER: In the post-pandemic era, companies should ensure they understand exactly how customers coped with the crisis along with the related new customer needs and behaviours that the crisis created. This requires shifting from traditional market research tools (e.g., surveys and big data) to more immersive and ethnographic methods to collect richer insights and data.

MARKETING. In the “new normal,” companies should implement a more bottom-up marketing strategy. Thinking needs to shift from a product-centric to a more customer-centric logic as well as from traditional marketing—based on the 4Ps or 7Ps of Kotler (Kotler, 2003; Kotler et al., 2001)—to the new experiential marketing and its 7Es (Batat, 2019).

COMMUNICATION AND BRANDING: Moving forward, companies should focus more on value and consider empathic communication and branding strategies. Consumers need to know that brands care and are active as social actors.

DIGITAL: This pandemic crisis has highlighted both the positive and negative sides of digital transformation, presenting an opportunity for a rethink. Companies should consider strategies that are more of a combination of the physical and digital, or “phygital” (Batat, 2019). This can help companies better connect their physical spaces to their digital spaces, offering more positive and productive experiences to employees and customers.

Cutting budgets, firing people, freezing projects, or canceling events is not the only way to respond when challenged by the unexpected. Whether the crisis at hand is technological, social, economic, political, or viral, the holistic recovery process outlined above can help firms move beyond comfort zones and emerge from any disruption as a faster and stronger competitor by developing new modes of thinking and acting.

But a successful recovery will always depend on how well business leaders understand what exactly enables the process to work. In other words, failing to disengage from established practices and ways of thinking will never help management regain control of a disrupted firm’s fate—it will only ensure the business remains a passive victim of the unexpected.

REFERENCES:

Atkinson and M. Hammersley, “Ethnography and Participant Observation,” in N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (London, UK: Sage, 1994), 248–261.

Bandura, “Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective,” Annual Review of Psychology 52, no. 1 (2001): 1–26.

Batat, Experiential Marketing: Consumer Behavior, Customer Experience, and The 7Es (London, UK: Routledge, 2019).

P. Bate, “Whatever Happened to Organizational Anthropology? A Review of the Field of Organizational Ethnography and Anthropological Studies,” Human Relations 50, no. 9 (1997): 1147–1175.

Collins and S. Crowe, “Research, Recovery and Mental Health: Challenges and Opportunities,” Mental Health and Social Inclusion 20, no. 3 (2016): 174–179.

Easterby-Smith and D. Malina, “Cross-Cultural Collaborative Research: Toward Reflexivity,” The Academy of Management Journal 42 (1999): 76–86

Kotler, Marketing Management, 11th Ed. (Prentice Hall International Editions, 2003).

Kotler, G. Armstrong, J. Saunders, and V. Wong, Principles of Marketing, 3rd European Ed. (Prentice Hall, Pearson Education Limited, 2001).