Samuel Patterson Smyth Pollock was born on December 15, 1925. He served in the Montreal Canadiens’ front office for 17 years (from 1947 to 1964) before taking on the role of general manager (GM) from 1964 to 1978. During his 14-season tenure as the Canadiens’ GM, he led them to nine Stanley Cup wins. He is the only GM to have overseen teams that won the Stanley Cup in more than 50 per cent of the seasons he served as GM (64.3 per cent). The next closest is 40 per cent (two out of five seasons).

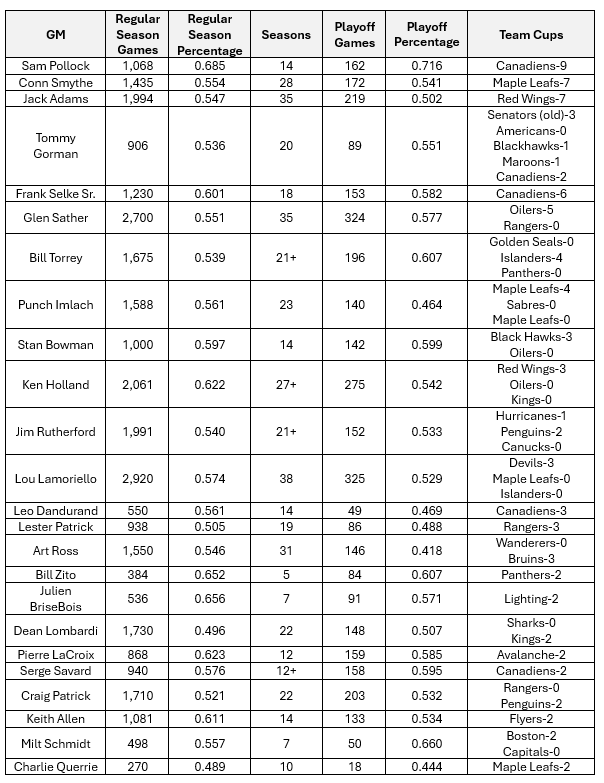

A century after Pollock came into this world, I offer some interesting data related to his extraordinary career. First, the Canadiens’ regular season winning percentage was 0.685 during Pollock’s tenure. The next highest among Cup-winning GMs was Irving Grundman, who succeeded Pollock as the Canadiens’ GM from 1978 to 1983. Second, the Canadiens’ playoff winning percentage was 0.716 during Pollock’s tenure. The next closest was the Bruins’ winning percentage of 0.660 during Milt Schmidt’s five-year tenure (see Table 1).

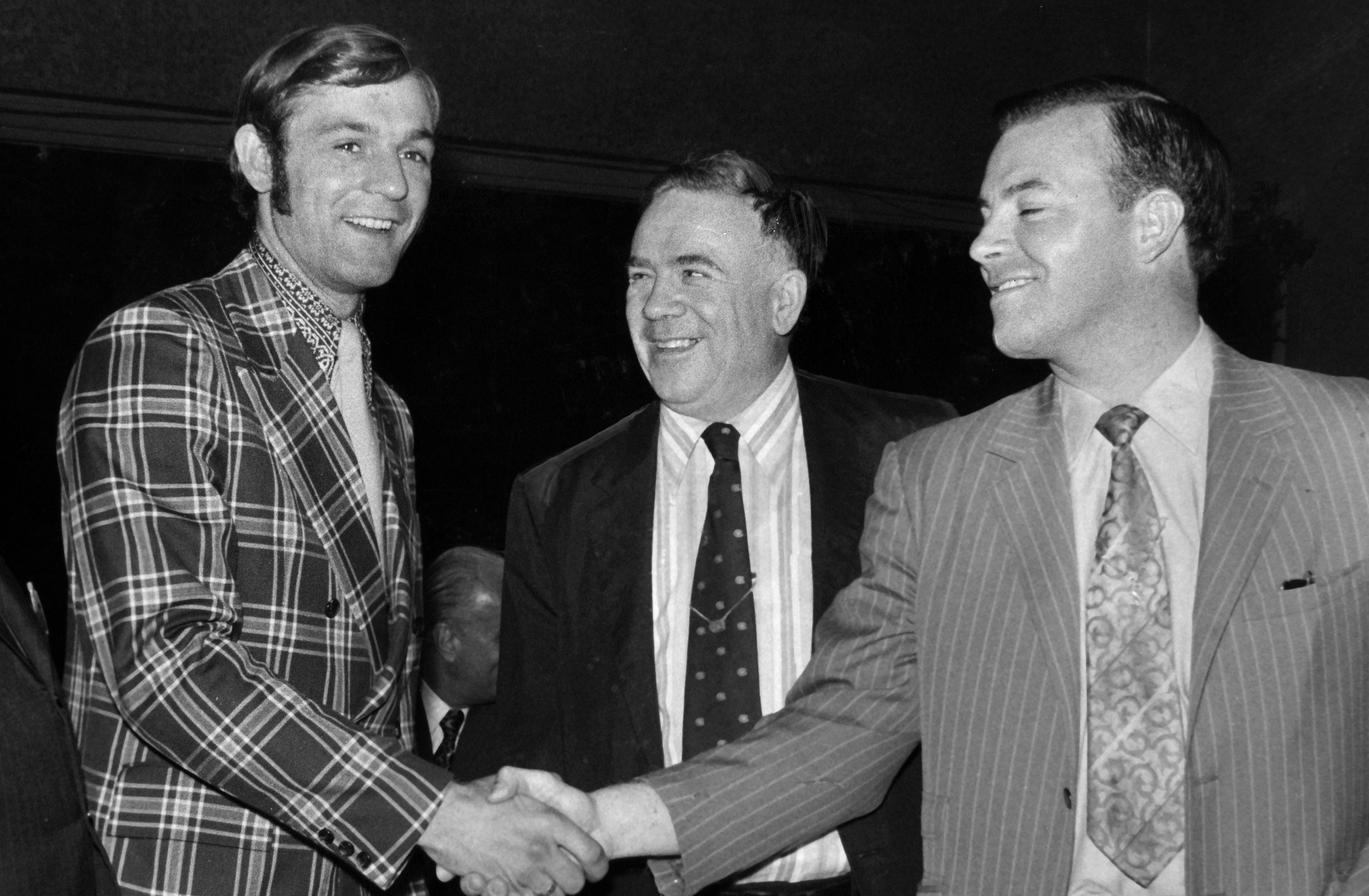

So, nine Cups in 14 seasons, the best regular season winning percentage (except for Stan Smyl, who was the interim GM of the Canucks for only two games), and, by far, the best winning percentage in the playoffs. And all of it under Pollock. But what made him such an extraordinary general manager? This article strives to answer this question, at least partially, through a personal story tied to his humility and the words of many who knew and worked with the NHL legend and/or were on the other end of a trade with him.

Changing the game

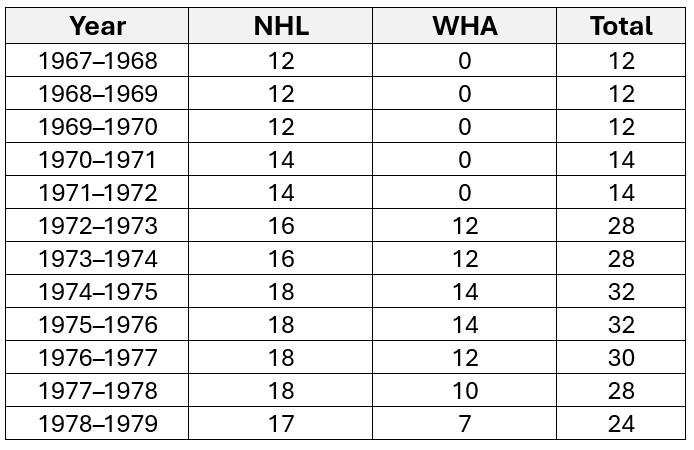

Pollock led the Canadiens during a period of great turmoil. During his first three years, there were six teams in the National Hockey League (NHL). The league expanded to 12 teams for the 1967–1968 season and in the 1970–1971 season expanded to 14 teams. In 1972–1973, as the NHL expanded to 16 teams, the World Hockey Association (WHA) started competing with the NHL with 12 teams. As the NHL and WHA expanded over the next two years, 32 professional hockey teams competed for players, coaches, and GMs. So, to those who would argue that Pollock was a GM in an era when there were fewer NHL teams, I would point out that there were, for two years, as many teams in the NHL/WHA combined as there are today in the NHL (see Table 2). When Pollock retired in 1978, there were still 28 teams in the NHL/WHA combined.

Pollock was the chair of the committee that recommended to the NHL owners that the league must expand to capture television revenues in the U.S. market and that it was important to expand dramatically by doubling the league to 12 teams as opposed to adding two teams per year, as some wanted to do.

To summarize, Pollock was in the middle of the NHL’s expansion from 1967 to 1978 and was one of the NHL’s GMs in competition with the WHL for coach, player, and scouting talent from 1972 to 1978. Next, I intend to discuss Pollock’s career before he became the Canadiens’ GM and then I will suggest several reasons for why I believe that Pollock was a leadership genius and the best GM in NHL history. He set records for excellence that will probably never be surpassed in professional hockey.

TABLE 1: NHL GMs With Two or More Cup Wins

Source: “General Manager Register – Regular Season,” NHL Records, accessed October 25, 2025

TABLE 2: Total Teams in NHL and WHL 1967–1968 to 1978–1979

Source: hockey DB, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.hockeydb.com.

An extraordinary career

As a younger man, Pollock played three major sports (hockey, baseball, and football) and “competed with distinction” in all three, according to the book Lions in Winter by Chrys Goyens and Allan Turowetz. However, his ability to manage other players, which was greater than his playing ability, was what brought him to the attention of the Canadiens organization. And this happened when he was a railway clerk. Before turning 18, as Goyens and Turowetz point out, Pollock was already leading “some of the best hockey teams and fielding some great baseball teams.” Meanwhile, in Todd Denault’s HabsWorld article “The Genius of Sam Pollock,” we learn Pollock caught the eye of the Canadiens at 17, while managing a softball team that included players from the Canadiens such as Toe Blake, Kenny Reardon, and Bill Durnan. He had also organized a successful local midget hockey team that supplied the Montreal Junior Canadiens with many players.

According to Denault, Pollock joined the Canadiens organization in 1946 at the age of 21, when he was given the responsibility of keeping track of every player in the Canadiens’ system and for watching out for infractions if his counterparts in the other five NHL teams tried to infringe on the teams owned or supported by the Canadiens. In 1947, he became the head coach and manager of the Montreal Junior Canadiens. In 1950, he led the Junior Canadiens to the Memorial Cup—the National Championship of the Canadian Hockey League, which included the Quebec Junior Hockey League and the Western Canada Junior Hockey League.

Many of the players who played for the Junior Canadiens went on to become stars with the parent club and became known as “Sam’s boys.” Jacques Lapierre, a former Canadiens player who went on to coach, was struck by the discipline, fairness, and strictness with which Pollock led his players on the Junior Canadiens.

In Denault’s article, Lapierre explains:“When you were one of Sam’s gang, you were taught to do things the right way. We had to wear a hat at all times, and a shirt and a tie. First class, that’s how he trained us right from the start. …. If guys were smart, they learned a lot about how to act and about discipline. It was very important to his system when you were a younger player. … Sam was very strict, but on the other side, he was very fair.”

Pollock and Kenny Reardon (a former all-star defenseman with the Canadiens) were given responsibility for the Canadiens’ extensive farm system in 1951. Pollock took responsibility for Eastern Canada and Reardon took Western Canada. The farm system had been built by Frank Selke Sr. (Pollock’s predecessor as GM) from 1946 to 1951, when he became the Canadiens’ GM after being fired by Conn Smythe as the Maple Leafs’ assistant GM. He instituted the farm system based on what he had seen Smythe do in Toronto. Pollock and Reardon strengthened the Canadiens’ weaker franchises and recruited talented players found by an improved scouting staff.

As Goyens and Turowetz described: “If there was a talented player anywhere in Canada, he was either playing in the Canadiens organization or being thoroughly analyzed by Canadiens talent scouts. Rare was the new player who graduated to an NHL foe without an updated file sitting in Forum headquarters.”

In 1958, Pollock led another Canadiens Junior team to another Memorial Cup—the Ottawa-Hull Junior Canadiens. Pollock took that same team into the Eastern Professional Hockey League in 1959 and won back-to-back championships in the six-team league in 1960–1961 and 1961–1962. In 1963–1964, the team was called the Omaha Knights and was coached by Scotty Bowman. They played in the Central Professional Hockey League and won the League Championship that year. So, Pollock built two Memorial Cup winners and three semi-pro champions from 1950 to 1964. In the 1958 Memorial Cup Championship, the opposition, the Regina Pats, was led by Kenny Reardon, Pollock’s colleague in the Canadiens organization. In the spring of 1964, Frank Selke Sr. retired and Pollock succeeded him as the Canadiens’ GM.

Although Reardon had also been considered for the GM’s position, he harboured no ill will towards Pollock and, as Denault noted, he stayed with the Canadiens as the vice president, saying: “Sam Pollock is the most intelligent man I’ve ever met, not just in hockey, but in life.” Pollock was 38 in 1964 and became one of the youngest GMs in NHL history. Toe Blake, who had coached the Canadiens to five Stanley Cup wins in a row from 1955 to 1960, stayed as coach. He would coach the Canadiens to another three Cups before voluntarily retiring in 1968.

“The true genius of Sam Pollock can be found in his ability to adapt. No other general manager was able to find the keys to success as quickly, nor as effectively as he did. And while most of this can be traced to his fertile mind, it would be unwise to overlook the man’s Spartan work ethic.”

Under Pollock’s leadership, the Canadiens won the Cup in his first year and would win in 1966, 1968, 1969, 1971, 1973, 1976, 1977, and 1978. In addition, the team that Pollock built won again in 1979—the year after he retired.

The data in Table 1 should lead astute readers to see Pollock as the best GM in NHL history. So now let’s turn to what made him a leadership genius by examining his humility and strong business orientation, along with his focus on putting the team above individual performers while having a long-term outlook rather than a short-term one.

Leading with humility

C. S. Lewis said that “humility is not thinking less of yourself; it is thinking of yourself less.” In the mid-to-late-2000s, I sent one of my doctoral students to Toronto to visit The Hockey News. I gave her two GMs to research. The first was Russ Farwell, the GM of the Philadelphia Flyers from 1990 to 1994. Under his tenure as GM, the Flyers missed the playoffs all four years and their winning percentage over 328 games was 0.479. My doctoral student found 15 articles about Farwell in The Hockey News, many of them interviews over the four-year period.

The second was Sam Pollock. My doctoral student found four articles from his 14-year tenure and none were interviews but instead they were stories about him as the Canadiens’ GM. It is said he would tell reporters to talk with the coach and the players, as they were the important ones in the Canadiens’ success. He did grant interviews in his office at the Montreal Forum, but only to talk about the players and coaches.

Goyens and Turowetz, in describing Frank Selke Sr.’s successor, said that Pollock “was a still quieter businessman who would spend his fourteen years at the helm shunning the limelight with even more vigour.”

Knowing when to boost spirits

In the 1966 Finals, after losing the first two games at home, the Canadiens were in Detroit to face the Red Wings. When the team arrived, Pollock took aside Jean Béliveau, the Canadiens’ captain, and sent him on a mission to beef up morale. In the book My Life in Hockey, Béliveau himself noted: “When we arrived in Dearborn [Michigan], Sam was in a mood for positive reinforcement. He handed me $500, with instructions to ‘find a good restaurant and take the boys out tonight. If you need more, pay it and I’ll reimburse you.’ Sam was very conscious of the fact that we needed relief from some of the pressure. And it worked. We won the next four games, three of them in Detroit.”

The Canadiens had won their second Cup with Pollock as GM and beat Detroit 4–2.

Maintaining an eye for good coaching

As mentioned earlier, Pollock kept Toe Blake as coach when he became the Canadiens’ GM and Blake coached the Canadiens to three Cups before voluntarily retiring after the 1967–1968 season. He then convinced Claude Ruel, the Canadiens’ chief scout, to be the Canadiens’ head coach. Ruel delivered another Cup in 1969. He continued for another season and a half before asking Pollock to let him go back to being the chief scout halfway through the 1970–1971 season. (The Canadiens had missed the playoffs in the 1969–1970 season.) Pollock asked Al MacNeil, the Canadiens’ assistant coach, to take the reins. He agreed and coached the Canadiens to an upset win over the Boston Bruins in the Stanley Cup Finals. Then, like Ruel, he asked to be able to step down and go back to the Nova Scotia Voyageurs, the Canadiens’ semi-pro team. Both Ruel and MacNeil cited the pressure of coaching in Montreal as the reason for voluntarily stepping aside. Waiting in the wings, after being let go as coach and GM of the St. Louis Blues expansion team, was Scotty Bowman.

Bowman had worked with Sam and coached for him when Sam was managing the Junior Canadiens and the two semi-pro teams (the Hull-Ottawa Canadiens and the Omaha Knights) mentioned earlier. Bowman went on to coach the Canadiens to five Cup wins, the last in the 1978–1979 season, after Pollock retired in 1978. Toe Blake and Scotty Bowman are considered the two best coaches in NHL history. Based on Cup wins alone: Bowman won nine Cups in 30 seasons, Blake won eight Cups in 13 seasons, and the next closest is Hap Day, who won five Cups in 10 seasons. Bowman won five with the Canadiens, one with the Penguins, and three with the Red Wings. Blake won his eight with the Canadiens and Day won his five with the Maple Leafs. As such, Pollock bookended his GM tenure with the two best coaches in NHL history. And what is fascinating is that he never fired any of his four coaches and each of his coaches coached the Canadiens to at least one Cup win. Furthermore, he never interfered with his coaches in spite of his success coaching at the Junior Canadiens’ level, where he and Billy Reay had co-coached the Juniors to the 1950 Memorial Cup Championship—he was the ultimate delegator.

Knowing how to scout

Pollock and his scouting team had an amazing ability to find, recruit, develop, and retain the best players possible. Granted, when Pollock became the Canadiens’ GM, there were only six teams in the NHL. However, the number of teams had grown to 18 teams when Pollock retired in 1978 and then there was the pesky WHA (see Table 2), whose teams paid large sums of money to attract talent from the NHL. Pollock and Kenny Reardon had worked with Frank Selke Sr. to build the Canadiens’ farm system from the late 1940s to the early 1950s. Pollock inherited this farm system in 1964 and then proceeded to dismantle it in favour of the draft system introduced in 1964 as the league contemplated expansion, which it undertook in 1967.

Pollock had an encyclopedic knowledge of every player in Canada and the United States who were involved in hockey at the junior and semi-pro levels. As Lions in Winter highlighted, Frank Selke Jr. described him as follows: “His files on our clubs do not contain a hundredth of what he keeps in his head. He tells us only what he wants to tell us. He knows all the players who belong to us, all the players who belong to the other teams in the NHL, their names, their ages, their strengths, their weaknesses. It is a living encyclopedia… but, I repeat, nobody but him has access to this knowledge.”

Initially, Pollock used the Canadiens’ farm system to find and recruit the best players, then he became immensely skillful at the draft. He gained the nickname “Trader Sam” due to his ability at making trades with other teams; his ability to trade for drafts was legendary.

The trade that tickles me the most occurred in 1964 just after Pollock became the Canadiens’ GM. He traded Guy Allen and Paul Reid to the Bruins for the rights to Ken Dryden and Alex Campbell. At 16, Dryden became the property of the Canadiens should he decide he wanted a pro hockey career. He was on his way to Cornell in 1964 and would not play his first NHL game until late in the 1970–1971 season. He played three seasons with Cornell University from 1966 to 1969, then spent a year with Canada’s national team. In 1970–1971, he played 33 games with the Nova Scotia Voyageurs before being called up to the Canadiens. Late in the 1970–1971 season, he played and won six games. He was then announced as the starting goalie against the “Big, Bad” Boston Bruins. The Canadiens with Dryden in goal won the series 4–3 and went on to win the Cup. Dryden won six more Cups with the Canadiens in the seven more seasons he played, beating the Bruins two more times in the playoffs. So, a rhetorical question: what did Pollock see in 16-year-old Dryden in 1964?

Pollock’s trades for draft picks became legendary. The most talked about is probably the trades he made with the Oakland Seals and the Los Angeles Kings to ensure he could select Guy Lafleur first in the 1971 draft. Denault describes several trades Pollock made for draft picks. Players drafted by Pollock included: Steve Shutt, Larry Robinson, Mario Tremblay, and Doug Risebrough.

As Denault wrote: “The true genius of Sam Pollock can be found in his ability to adapt. No other general manager was able to find the keys to success as quickly, nor as effectively as he did. And while most of this can be traced to his fertile mind, it would be unwise to overlook the man’s Spartan work ethic.”

Another trade was for Frank Mahovlich, who he acquired from Detroit on January 13, 1971, for three pretty good players. Mahovlich would help the Canadiens to win Cups in 1971 and 1973. In 1973, when Pollock drafted Bob Gainey, sports journalists said, “Bob Who?” Gainey would help the Canadiens win five Cups—his last in 1986, when he led as the team’s captain. He is one of only two team captains to win a Cup as a team captain and as a GM, with Eddie Gerard being the other.

Putting team building first

Pollock’s ultimate goal was not to win a championship but to build a better team. As highlighted in Lions in Winter, the man himself said: “The Gainey draft developed out of a very large set of circumstances, … I always tended to look at the overall or big picture, such as how many players we had, and how many players we were going to protect in a given year. Very seldom was my philosophy to win a championship first, especially at the expense of developing a good team, because if you worried about winning championships in one particular year, you could make some very bad mistakes.”

When describing Pollock’s perspective on putting the team first, Goyens and Turowetz wrote: “No player, no matter what his past contribution, was better than the team itself in the organizational scheme of things. A player may be more valuable to his team than a teammate, but he could never be more valuable than the team.”

This philosophy led to several players such as J.C. Tremblay, Marc Tardif, Rejean Houle, and Frank Mahovlich going to the WHA when they came calling with more money than the Canadiens were willing to pay. It led to Pollock letting Dryden sit out a year (1973–1974) over a pay dispute. And it led to Pollock’s creativity as to how he structured Guy Lafleur’s compensation to retain him in the Canadiens organization.

Pollock compensated his players to ensure team harmony and used the Canadiens’ bonus system as the great equalizer in Montreal, with several of the bonuses being team-oriented.

Playing the business game

To be a successful NHL GM, Pollock believed you had to know how to run a business. In Lions in Winter, this is explained in his own words:

When I started, front office management might have been 50 percent hockey acumen and 50 percent business skills.

By the 1970s, it was 25 percent and 75 percent. Now, I think it is 15 percent hockey sense and 85 percent business skills. If you want to be successful in this business, you have to follow sound business principles. That means keeping expenses low and profits high. If you follow good business principles, you will do your financial homework.

That usually means you’ll do your hockey homework too and you’ll have a competitive team. Winning is what this is all about and the best way to ensure you’ll win is to do your homework, all the time. Because just like on the ice, there is a competitor out there doing his homework and waiting for you to make a mistake.

If the guy running your organization has trouble reading a balance sheet, the organization will be in trouble. Today’s sports administrators have to be first businessmen and alert to all opportunities.

Pollock’s financial acumen was one of reasons he was so successful. But his pursuit of low expenses did not mean he treated his players poorly. He neither overcompensated nor undercompensated them—he paid them appropriately based on their value to the team. And he lost very few players to the WHA.

Pollock’s contribution to the Canadiens

In all the books and articles I have read on the Canadiens and Pollock, there is one aspect I have not yet seen covered and I offer it now for your consideration.

From the 1910–1911 season to the 1945–1946 season (36 years, actually 35 years, as the Cup was not awarded in 1919 due to the Spanish flu), the Canadiens won five Cups—a 14.3 per cent record. From the 1979–1980 season to the 2024–2025 season, a 46-year period (actually, 45 years, as there was no season in 2004–2005 due to a player lockout by the owners), the Canadiens won three Cups—a 6.7 per cent record. In between, from the 1946–1947 season to the 1978–1979 season (33 years), the Canadiens won 16 Cups—a 48.5 per cent record. To put this in perspective, the team with the next most Cups is the Maple Leafs and they have a winning percentage of 12.6 per cent over 106 years from 1917 to 2025 (given the Cup was not awarded in 1918–1919 and 2004–2005).

The common factor from 1946 to 1979? Sam Pollock.

Obviously, Frank Selke Sr. rightly gets the credit for the Canadiens’ 11 trips to the Finals and the six Cups won in his 18-year tenure as the Canadiens’ GM from 1946 to 1964, but behind the scenes Sam Pollock was building the farm system (along with Kenny Reardon) in his role as director of player personnel. He was feeding the parent club with star players from the Canadiens’ farm system. Players who Pollock sent to the parent organization included Dickie Moore, Henri Richard, Claude Provost, Phil Goyette, J.C. Tremblay, Gilles Tremblay, Ralph Backstrom, and Bobby Rousseau.

When Pollock built the Junior Canadiens Memorial Cup winner in 1958, his coach was Scotty Bowman. The team they beat was another Canadiens junior team, the Regina Pats, built by Kenny Reardon with future Canadiens stars such as Terry Harper, Dave Balon, Bill Hicke, and Red Berenson. And it was the team Pollock built with Bowman as coach that won the Cup in 1978–1979, after Pollock retired, with Irving Grundman as GM. Grundman only won that one Cup. So, from 1946 to 1979 the common factor behind 16 Cup wins was Sam Pollock. This does not mean I am suggesting that Selke Sr. and Grundman should not get the credit for their Cup wins as GM, but I do believe that Pollock’s contributions to those seven Cup wins needs to be acknowledged. He was the common factor.

Lessons from an extraordinary career

Pollock retired in 1978 at the age of 52 after working with the Canadiens for 31 years following the sale of the Canadiens from the Bronfman brothers to Molson Breweries, which, as Goyens and Turowetz noted, reached into The Canadiens “upstairs dressing room” with Pollock’s departure. “During the seven-year ownership of the club by Peter and Edward Bronfman’s Edper Investments, Pollock had acquired an equity interest in the company. When the sale took place, he was deeply involved in the Edper scheme of things and reluctant to divest.”

After retiring from the Canadiens, Pollock pursued other interests such as managing his investments and collecting art. He served on several boards and received the Order of Canada and the Order of Quebec. He subsequently returned to baseball and from 1995 to 2000 became the chair and CEO of the Toronto Blue Jays.

As Denault noted, “Sam Pollock never relaxed, never stopped working, and ultimately, never stopped winning.” He passed away in 2007 following a long battle with pancreatic cancer, but he left behind a legacy that included leadership lessons with value far beyond the world of sports.

Pollock exhibited humility by thinking of himself less. He knew when his team needed him to do something out of the ordinary. He developed a team that found, recruited, developed, and retained the best players and coaches. The four coaches he worked with all won at least one Cup as the Canadiens coach and he never fired any of them. His ultimate goal was to build a better team—not to win a championship. Pollock put his team ahead of the individual players. He was an outstanding business leader.

This leads to several questions for CEOs and chairs of organizations, be they for-profit or not-for-profit:

-

- First, are you thinking of yourself less?

-

- Second, are you a discerning leader who knows when to do something out of the ordinary to pick your organization up?

-

- Third, have you helped your senior HR person develop a system that finds, recruits, develops, and retains the best employees and leaders (in hockey terms, the best players and coaches)?

-

- Fourth, are you more concerned with building and developing a better organization over the long term and letting performance be a penultimate goal rather than focusing primarily on short-term performance?

-

- Fifth, does your organization come first or do you put any one employee or manager in your organization (including yourself) ahead of the organization?

-

- Sixth, can you read and understand financial statements?

Success is never guaranteed, but if today’s leaders take the time required to seriously consider these questions they will have a better shot at having their careers remembered 100 years after they were born.

About Author

W. Glenn Rowe is Professor Emeritus, Ivey Business School at Western University. He served in the Canadian Navy for 22 years and was Commanding Officer of Minor Warships in his last three years. He entered academia in 1990. He has taught at Memorial University of Newfoundland, Texas A&M (while a PhD student), as an invited professor at Royal Roads University, American University of Beirut, and IPADE Business School in Mexico City. Since joining Ivey in 2001 he has served as Coordinator, General Management PhD program (2002–2009) and as Director, Ivey’s EMBA Program (2009–2012). He has taught in Ivey’s HBA, MBA, MSc, MMA, AMBA, EMBA, and PhD programs. Recently, he taught a Corporate Strategy elective in Ivey’s MBA and HBA programs. Also, he co-taught an MBA course in Responsible Governance. Further, he has taught in Ivey’s Executive Education programs and has facilitated Case Teaching/Writing Workshops for faculty in business schools and colleges in the United States, Lebanon, Qatar, Mexico, and Canada. Recently, he gave presentations to four universities in Kyrgyrstan and Tajikstan on Case Methodology in the classroom. He served as the Executive Director, Ivey Publishing (Ivey’s case publishing house) from January 2016 to December 2019. Rowe is a co-author of two textbooks currently in use: Cases in Leadership (5th) and Strategic Analysis and Action (10th). He is an active researcher (with several articles on leadership using the National Hockey League) and has written/co-authored 70+ organizational cases. He recently presented to the YPO Great Lakes Ontario Chapter on the topic of corporate strategy for Multi-Business Enterprises. He is a frequent contributor to the Ivey Business Journal. Contact: growe@ivey.ca.

- W. Glenn Rowehttps://iveybusinessjournal.com/author/growe/July 20, 2022

- W. Glenn Rowehttps://iveybusinessjournal.com/author/growe/July 13, 2022