Professional misconduct occurs when behaviour falls outside the law or below standards outlined within a code of conduct. Examples include confidentiality breeches, falsifying evidence, financial fraud, and noncompliance with rules and regulations. It has resulted in criminal charges against high-profile individuals such as Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes and Sam Bankman-Fried of FTX. But it can be found everywhere, with many less prominent cases leading to significant and lasting reputation and financial damage.

When reported in the media and on social media platforms, or within organizations, professional misconduct is often billed as the actions of a rogue or oddball. This narrative is based upon the common assumption that greed is responsible for creating so-called corporate bad apples. This is great for media reporting and storytelling in film or fiction—where greed makes for terrific plots (just try to imagine Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street or Charles Dicken’s A Christmas Carol without it).

Unfortunately, blaming greed for professional misconduct is also reassuring for the rest of us because it cleanses our hands of culpability. And that’s a problem because the cause of business world misconduct is far more complex than typically imagined.

Greed does not explain the unethical behaviour of individuals who do not stand to benefit financially from their actions. Blaming greed for misconduct also overlooks the responsibility of others to ask questions and call out undesirable behaviours. Furthermore, the rogue narratives that tend to appear when high-profile cases of professional misconduct emerge tend to ignore the fact that people do not exist in a vacuum. And when we decouple the bad behaviour of business professionals from the environment within which they operate, we overlook an opportunity to prevent it.

This IBJ Insight is based on “Why Individuals Commit Professional Misconduct and What Leaders Can Do to Prevent It,” an open access article I published in California Management Review with former University of Exeter Business School PhD student Navdeep K. Arora and Warwick Business School professors Graeme Currie and Dimitrios Spyridonidis. We collectively set out to rethink the causes of professional misconduct after being presented with a unique opportunity to interview inmates in a U.S. Federal Prison who were jailed for committing white collar crimes.

“Greed does not explain the unethical behaviour of individuals who do not stand to benefit financially from their actions. Blaming greed for misconduct also overlooks the responsibility of others to ask questions and call out undesirable behaviours.”

Over a period of 16 months, as an inmate himself, Navdeep interviewed 70 other male inmates who had broken rules and laws in different environments, including family businesses, and a variety of sectors, such as accounting, banking, government, medicine, science, and technology. This gave us a distinct lens to study professional misconduct from the perspective of individuals guilty of professional misconduct who were coming to terms with their actions. Navdeep sadly passed away during the final stages of our research after contributing to our findings by drawing on his expertise in innovation, strategy, digital transformation, and reputation management.

According to our study, professional misconduct frequently resulted from what we describe as “flawed intuition”—a consistent pattern of instinctive muddled logic by individuals—which is influenced by organizational and industry factors and a combination of individual behavioural triggers.

Simply put, we found the wrong combination of triggers alongside a lack of personal reflection and/or feedback from leaders can cause people to cross ethical and legal lines.

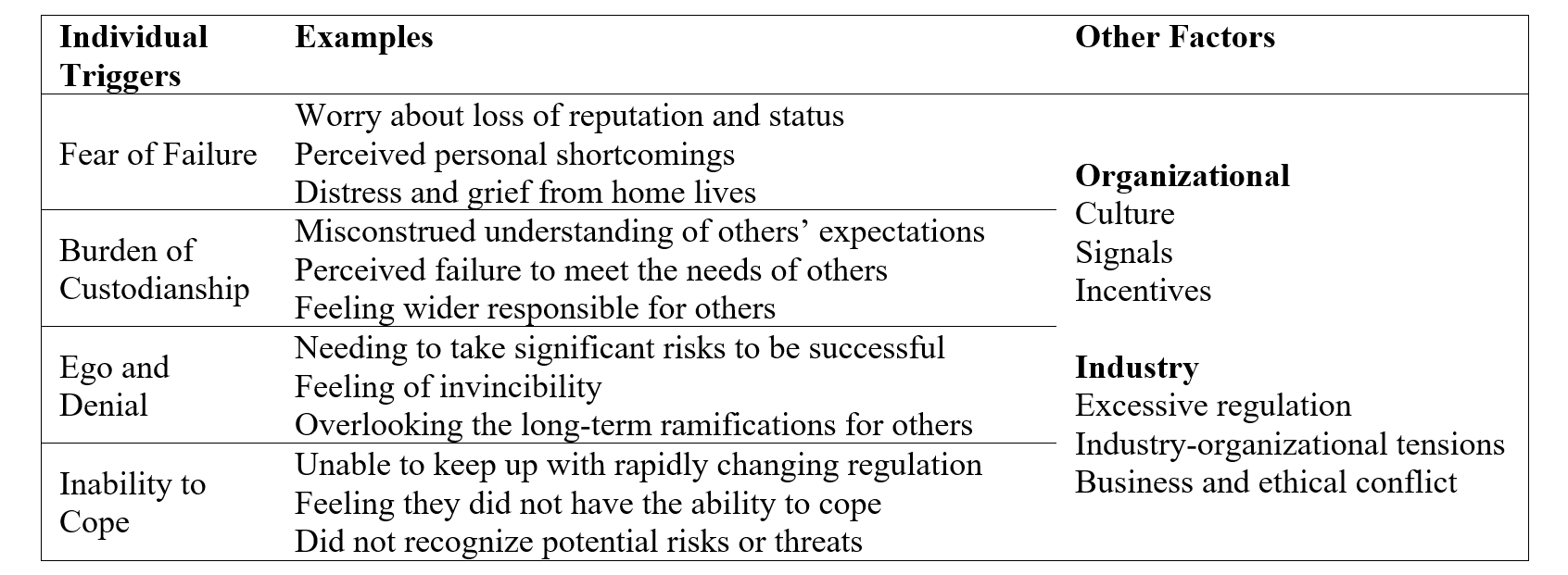

We further found that there were four connected individual behavioural triggers that were common across the inmates we interviewed: fear of failure, burden of custodianship, ego and denial, and inability to cope.

- With fear of failure, participants were ironically worried about losing their reputation and status. This often stemmed from their self-perceptions of shortcomings and was often inflamed by emotional stress and grief from their personal lives, which included spousal death, child suicide, divorce, and addiction, among others.

- Burden of custodianship was the misconstrued understanding of what others expected of them, whether that was line managers, customers, or patients. They were concerned that they were failing to meet their expectations.

- The third behavioural trigger was ego and denial where individuals felt they needed to take significant risks to be successful and were invincible. In some cases, they did not recognize their behaviour was a problem or see the long-term implications for others.

- Fourth, the inability to cope was when people felt they could not keep up with rapidly shifting regulatory expectations and thought they did not have the capability or capacity to manage.

Participants in our study didn’t seek to excuse their behaviour or shift blame. But while individual decisions had led to their professional misconduct, we found it is important to recognize the wider impact of organizations and industries when examining why professional misconduct occurred.

Within organizations, we identified three contributing factors: culture, signals, and incentives. In many cases we examined, workplace culture was strongly focused on a narrow set of outcomes such as sales, tax cuts, and financial performance. While strong signals from leaders around financial performance existed, signals around desired behaviours were often weak. Moreover, incentives were often perverse around a narrow set of criteria with few ethical questions asked about how goals were achieved.

At an industry level, participants explained the challenge of mounting regulatory expectations, which was common across different sectors, from banking to health care and accounting to consulting. Within this context, tensions emerged between organizational incentives and regulatory compliance. To paraphrase one inmate, “There are no rewards for compliance but there are penalties for not meeting your targets.” This raises a potential for conflict between business and ethical decisions. Excessive regulation combined with intense target cultures runs the risk that individuals find workarounds when regulation becomes unwieldy and managers focus their attention on targets, often overlooking how they were reached.

Table 1: Causes of Professional Misconduct

Individuals make their own decisions and should be responsible for them. But as noted above, greed is an unsatisfactory explanation for professional misconduct, which is a wicked problem that does not lend itself to a simple solution.

Our research found professional misconduct is better understood when seen through the concept of flawed intuition where people are influenced by a mixture of individual behavioural triggers, organizational context, and the wider industry environment, combined with a lack of personal reflection and/or feedback from others. And because people professionally misbehave as a result of a complex interplay of their own circumstances, which may involve self-interest, alongside the organizational and environmental context in which they exist, solutions need to cut across multiple levels.

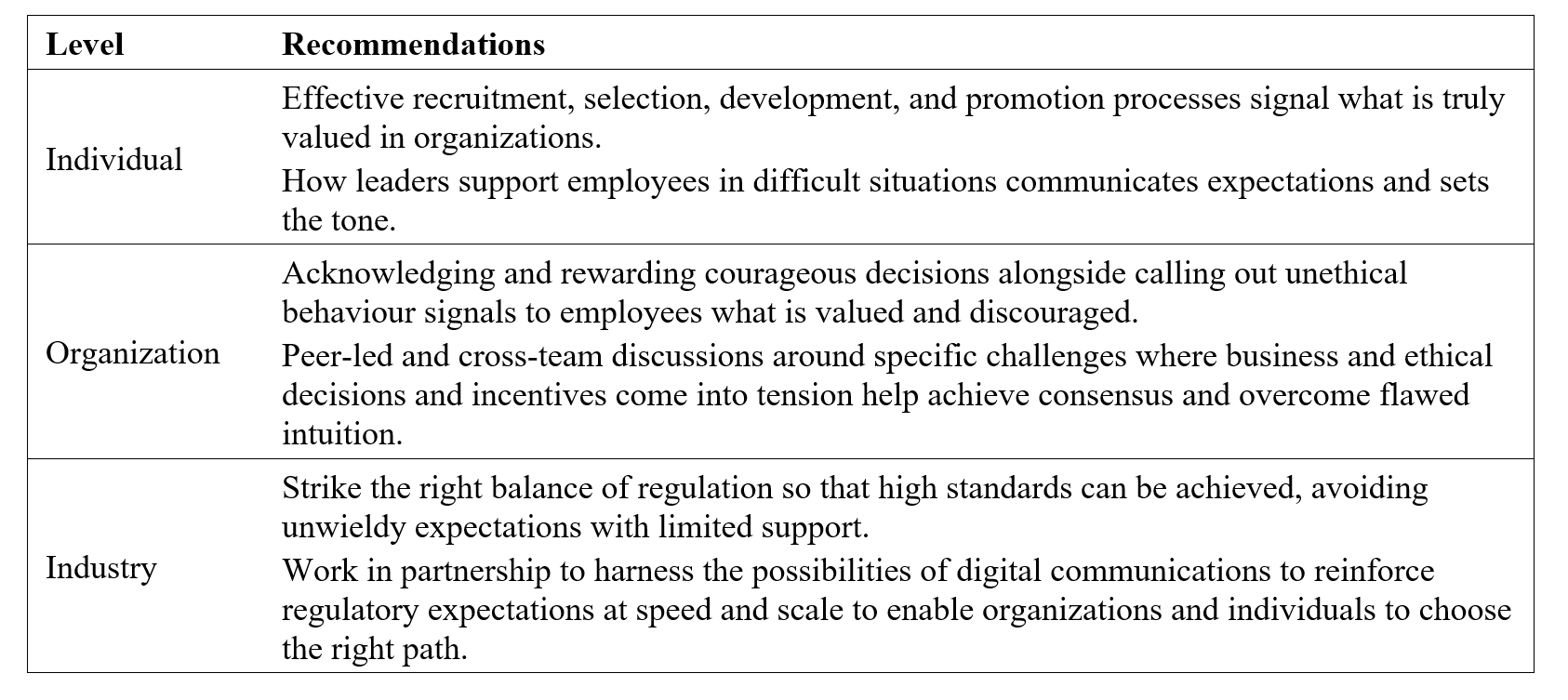

At the individual level, recruitment, selection, development, and promotion processes are essential for signalling to individuals what is truly valued in the organization. People face all kinds of setbacks in their lives, and how leaders respond and give support in times when stress and undesirable behaviours emerge communicates an important element of the organization’s culture.

At an organizational level, a command-and-control approach is less effective in contexts where professionals value autonomy. Instead, acknowledging and rewarding courageous decisions and calling out unethical behaviour sends signals to employees about what is valued and discouraged. Peer-led and cross-team discussions around real (not hypothetical) issues where business and ethical choices and incentives are in tension can help to avoid siloed thinking and encourage consensus across teams.

At an industry level, regulators have a role to play in finding the right balance of regulation. Every industry needs regulation to encourage good standards, behaviours, fairness, and safety. But while it is tempting to assume that more regulation leads to better outcomes, increased regulation can backfire. Indeed, a larger code of conduct book, along with more agenda items, or an additional oversight committee could actually perversely increase malpractice as people facing unwieldy compliance take shortcuts. This is particularly the case if regulation increases and support to implement remains the same.

Rather than making organizations and individuals feel constrained by mandates, we need to enable them to make the right choices by fine-tuning the level of regulation while harnessing the possibilities of digital communication tools to reinforce expectations at speed and scale.

Table 2: Reducing Misconduct

The history of business has repeatedly shown that toxic behaviours can pervade teams, organizations, industries, and even societies. And while it is an uncomfortable truth, we need to accept that professional misconduct isn’t just a greed issue. It is a risk we all face, particularly with rapid technological change and a volatile political and economic environment expanding the grey area between right and wrong, trailblazing and swindling. As a result, it has never been more essential for leaders to recognize their role in the prevention of misconduct and redress incidents of it early.

About Author

William S. Harvey is Professor of Leadership at the Melbourne Business School and an International Research Fellow at the Oxford Centre for Corporate Reputation.