Marketers might not care to spend time pondering the old adage that asks, “If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” But here’s a new adage they should think about if they are interested in driving faster revenue generation, “If a customer signals their purchase intent in the marketplace and no one is around to hear it, does the cash register ring?”

A major shift in marketing is underway that involves moving from an approach geared to delivering a marketing plan based on market segmentation to one that plans real-time engagement with individual customers to find the right ones and close them. With traditional marketing, the time it takes to convert a prospect into a paying customer is lengthy and most companies don’t have the luxury of time nor the patience of investors. As a result, innovative marketers found a way to accelerate revenue generation by watching for signals customers give off online and then acting on insights gained to engage with customers and enable their progression from prospect to purchaser.

Simply put, these marketers moved on from the slice and dice of data associated with marketing planning to what might be termed the sensing of customer cues to follow. That is part of contact-based marketing (CBM), the subject of this article, which aims to help you plan or improve your own CBM. But first, let’s discuss why this change is happening before reviewing how marketers are making investments in people, processes, and technology to achieve better near-term revenue. The following focuses on B2B marketing, although CBM applies also to B2C marketing and many of the observations are appropriate for both arenas.

Traditional B2B Marketing

Marketers operate according to the core principles of identifying and satisfying customers’ needs in a competitively superior manner to achieve revenue and profit objectives. Marketing plans are generally developed annually using primary and secondary research as inputs followed by market and business analysis and market segmentation. Plans include target market selection, positioning, and strategies and tactics associated with the delivery of the marketing mix—the 4Ps of marketing, product, price, place, and promotion—then budget, implementation, and measurement considerations. Or so goes the theory. This approach has worked well for a long time, but many firms are now finding there are several material shortcomings in this approach for reasons such as the following:

Volatile markets: Markets are increasingly volatile and dynamic, while the marketing planning process is often done annually, which is too slow to accommodate the rapid macro and micro changes to be found in most markets and industries. Some companies have made marketing plans into dynamic documents, updating them periodically to accommodate change.

Clusters over segments: Market segmentation groups customers according to the needs they have in common. Segmentation is necessary but no longer sufficient for finding and closing opportunities. That’s because markets are fragmenting with more customers—even those with similar needs—exhibiting very different behaviours. Behavioural differences can include product choices and customization, pricing bundles, the timing of purchases, how firms find and engage with their suppliers, and the length of time it takes to make a purchase. When customers behave differently, segmentation makes less sense than categorizing customers by behaviour, which is called clustering. It’s not uncommon to find customers within a given cluster drawn from multiple market segments. One electric vehicle company, for example, groups industrial customers according to factors such as the anticipated duration of their purchase cycle, their financial strength and spending based on ability to afford, and the alignment of their applications with the company’s solutions. This is different from “firmographics,” where customers and prospects are categorized according to objectively measurable attributes such as their revenue, employment, industry, and tech stack.

Competitor proliferation: Add to these changes the proliferation of competitors from around the corner and across the globe. With this increase in competition has come a decline in differentiation and the commoditization of solutions—many products are simply more substitutable and lack enduring differentiation. Given this, it has become harder for firms to maintain their margins at historical levels. Strong brands help retain differentiation and delay margin erosion, but branding can only accomplish so much in cluttered marketplaces.

Dialogue over monologue: The era is long past when companies were solely in control of their message, when marketing communication was a monologue broadcast from the company to the customer across one-way media like TV or radio, and when products were homogeneous, with little room for customization and co-creation. Today, companies engage in a dialogue with their customers as messages are carried in both directions: from company to customer, and from customer to company. Customers also carry their messages to other customers directly and indirectly, with their reviews. Communication only works when both directions of travel are managed; the traditional principles of marketing close the feedback loop from the customer with marketing research but this is in aggregate or for a segment as a whole and lacks insight into each individual who may then feel unheard. The principles of relationship marketing address this shortcoming by marketing to the individual, developing insight into their needs and requirements, customizing the firm’s solution for the value each seeks, and engaging to manage the customer experience over a lifetime of purchasing.

Relationships over Transactions: While catering exclusively to market segments may still be beneficial for some firms— particularly where they enjoy the brand strength that comes from considerable differentiation and market share—it has become increasingly common over the last 20 years for companies to cater to the individual customer, treating each as a market of one. This is the essence of relationship marketing. Each customer receives individualized treatment to give them value that competitors cannot provide because other firms don’t have customer-specific insight that can only come from a progressively deeper learning relationship.

The principles of the planning of customer relationships are usually based on the IDIC model popularized by Don Peppers and Martha Rogers in a number of books, textbooks, and articles, such as The One to One Future. IDIC is an acronym for identify, differentiate, interact, and customize, which gives strategic weight to the analysis and management of customers’ behaviours rather than just their cognition, the usual battleground for marketing competition. The IDIC model also invites marketers to mass-customize both communications and their value creation, something that companies now know can usually be done at scale without sacrificing profitability. This methodology has worked very well. So well, in fact, that an entire software industry was born: customer relationship management (CRM) software. Software companies have conflated CRM with relationship marketing. I prefer to keep the two concepts separate to keep the focus on relationships which are central to customer management rather than software which is a generally useful tool. (I have written two books on this topic: Relationship Marketing: New Strategies, Techniques and Technologies to Win the Customers You Want and Keep Them Forever and Managing the New Customer Relationship: Strategies to Engage the Social Customer and Build Lasting Value.)

Companies have analyzed their individual customers according to value, needs, behaviours, and influence, and triaged them to make sure that only their best customers receive the company’s best value. Before adopting this approach, all customers in a segment would receive similar value, which meant that bad customers were over-rewarded and good ones received less value than was their due. Naturally, good customers headed for the door and bad ones brought their friends so the customer portfolio became distorted. From this experience, companies have learned that it is only the right customers who are right for the firm, which has put an end to the old refrain “the customer is always right.” We will discuss the “right” customer shortly in the context of the ideal customer profile.

Relationship marketing has been particularly helpful for managing and growing those customer accounts with which the company already does business, their current customers. But what of the rest of the world—the companies that are not yet customers? Firms are now paying more attention to customer acquisition, along with developing revenue growth from current customers, because relationship marketing’s longer time horizon has not always delivered near-term results.

Revenue Generation

Revenue generation (RevGen) typically seeks to deliver results in a much shorter time horizon than has been the case with “traditional” marketing—and relationship marketing, too—so much so that many firms now consider RevGen to be a separate function in their business. It is not uncommon for larger firms to have a chief revenue officer (CRO) as well as a chief marketing officer (CMO) because their roles are different. Let’s discuss the similarities and differences of these two roles, and their respective time horizons, to understand why contact-based marketing fills an important gap.

The CMO plans and manages the strategies and processes that position the firm’s brands in the minds of its customers and prospects. The CMO is tasked with identifying and satisfying customers’ needs in a competitively superior manner to build profitability. Among their most important roles, they create and deliver communications to drive brand awareness and preference and product/solution interest. They also manage customer relationships, customer lifetime profitability, customer purchase intent (which become leads for the firm’s sales funnel) and actual purchases by customers. The CMO creates the strategic umbrella for the firm and its brands and both the CRO and the sales function operate under this umbrella.

The CMO’s time horizon is typically longer than that of the CRO, who orchestrates people, processes, and technologies across the firm’s channels to accelerate revenues and deliver the revenue targets in the marketing plan. The CRO is responsible for aligning the delivery of customer value with the brand’s positioning and other aspects of the marketing plan, so the CRO role is interdependent with marketing. The CRO looks for revenue growth by identifying and working with sales to develop new accounts, and growing revenues within existing accounts—again, working with sales. Growth within existing accounts can come from a number of sources, including what has been termed “lift and shift” or “upselling and cross-selling.” I’m not fond of either term as I see the perspective being that of the seller rather than the customer. In my experience, no customer has ever asked to be upsold or cross-sold. To focus on upselling and cross-selling is to have a sales orientation rather than a customer orientation; the CRO tries to balance these two approaches. Herein is one of the challenges for the CRO and the RevGen team: to focus on listening, understanding, and addressing customers’ needs while achieving the company’s revenue goals. To do the reverse would mean a company finding ways to sell rather than acting as a sort of unaccredited purchasing agent for the customer.

To align the company with its customers’ needs, B2B firms prioritize customer success to ensure that customers receive the benefits they expect over the lifecycle of product, service, or solution consumption. Only transaction-oriented companies ignore the importance of customer success today. Companies that prioritize customer relationships want to earn a customer’s lifetime of purchasing. Customer success helps these companies keep their customers loyal by habituating their behaviours and giving them no reason to leave. Customer success invites active listening to find solutions that customers value, which can lead to the upselling and cross-selling mentioned earlier, but this time done for and with customers, rather than acting only in the company’s interests.

Active listening is typically interpersonal in nature, but it does not have to be. Technology plays an important role in helping firms to listen to their customers. This is the domain of signals and their sensing, particularly in cyberspace.

The Signaling of Purchase Intent

In our personal lives, we are very alert to social signals because of the information they carry. We are used to deciphering facial expressions, body language, phraseology, and tone and delivery, whether for advantage or to recognize a possible threat. When someone smiles at us, we may perceive support and encouragement. If someone laughs with us, we may welcome this as an emotional gift and a strengthening of our relationship. A frown may indicate displeasure, and so on. We are used to receiving and sending signals. It’s part of being human and connected. Signals are important for the overt and hidden messages they carry, so everyone pays close attention.

“Companies that are not actively investing in and upgrading their sensing are placing themselves at a material disadvantage and providing space for competitors to gain revenue at their expense.”

In a business context, the sensing of signals is uneven. This has always been the domain of sales; the sensing of signals has since expanded to include customer success and today’s RevGen marketer. While some firms invest heavily in people, processes, and technologies to make sense of signals in real time and to act in a way that benefits both customer and company, this is not universally true. Companies that are not actively investing in and upgrading their sensing are placing themselves at a material disadvantage and providing space for competitors to gain revenue at their expense. It makes sense for all companies to consider the many benefits to be had from the active search for and interpretation of signals, including extracting meaning to enhance the customer’s journey, prioritizing opportunities to make pursuits more efficient, finding new revenues from new customers, hearing and developing existing customers or revenue growth, and managing communications and engagement so that purchase intent is converted into sales, either quickly and directly (such as with special offers) or over time (with funnel management).

When applied to new customers, RevGen senses signals not only when customers are about to buy but also earlier—sometimes even before customers themselves might know where their behaviours are headed. RevGen needs technology to sense, manage, and orchestrate responses at scale. Manual approaches to managing B2B sales funnels are no longer good enough for many reasons: they are not fast or detailed enough, nor sufficiently predictive or informed. As a result, they don’t perform well when converting leads or sharing information in real time with the people who need it most, to pick two shortcomings.

Signals providing opportunities to manage demand can be found directly, such as from engagement with customer success personnel and from sales interviews. These signals can then be entered manually into a system for signal management and data sharing. Signals can also be found using technology in cyberspace.

There are two main types of signals, micro and macro:

Micro signals comprise the data a company can receive when a potential customer opens an email, visits a website, completes a form, enrolls in a blog or seminar, completes a profile online, or visits a competitor’s website. These are the signals a customer sends when engaging digitally online—and not necessarily only on the company’s website or other digital properties but also elsewhere on the Internet.

Macro signals look for events specific to the prospect, their purchase decision-making unit, the industry within which they compete, and other contextual information. These are the signals that a prospect sends by virtue of conducting business in their industry—e.g., government filings—and the contextual factors that act upon their businesses to which they must likely respond, e.g., increasing regulations, declining margins, or market entry by foreign competitors.

Combining micro and macro signals has the potential to yield deep insights. A company combining both micro and macro signals with what it already knows about customers in its CRM solutions has the potential to be more insightful, faster, nimbler, and more relevant to its customers and prospects.

For example, you might find from macro signals that a prospective customer is laying off staff and that the prospect’s financial performance has not been strong recently. Purchase decision makers and influencers remain intact in the company. From micro signals, you might observe that purchase decision makers are visiting competitors’ websites. Recent requests for proposal (RFPs) emphasize price over performance for the solutions they are seeking to acquire. Even amidst weaker financial results, the prospect is still adding to their tech stack (the technology they have in place). You perceive an opportunity from these signals and must now decide with whom to engage, how to proceed, what benefit to offer, what communication to employ, and in what channel. Perhaps you are overwhelmed with the decisions to be made for this one opportunity. Unfortunately, you also have a huge number of other decisions to make.

It is not easy to manage micro signals just from a company’s existing customers. The challenge becomes yet more complex when layering on new potential customers’ micro signals, proactively gathering macro signals, and searching for top-of-funnel opportunities at scale locally and globally, and then combining these micro signals with macro signals and CRM data to find deep new insights and chart a path forward. Doing this manually can overwhelm even the hardest working, best intentioned people. Luckily, a solution to the challenge of being overwhelmed can be found by making the right additions to a company’s own tech stack, as discussed shortly.

Contact-Based Marketing

Contact-based marketing (CBM) is a real-time marketing strategy that uses signals such as those just discussed to engage with prospects and customers, answer their questions, solve their problems, and help them on their customer journey with very specific solutions to the issues they have demonstrated they face. The objective of CBM is typically to generate revenues faster. CBM is closely associated with the principles of relationship marketing discussed previously in the sense that the focus remains on the individual, who is differentiated from other customers. But while relationship marketers already know their existing customer which allows them to differentiate their customers—that’s not typically the case for CBM, where the customer is often new and not well known. As a result, CBM differentiates customers based on their alignment with ideal customer profiles (ICPs).

Even before signals can be managed, the starting point for CBM is to first identify ICPs. CBM must find the right prospects and customers from all the signals available in a cluttered and fast-changing data universe. The ICP is developed according to the factors that matter most in a business. It asks and answers the question, “If only the right customer is always right, who is the right customer?”

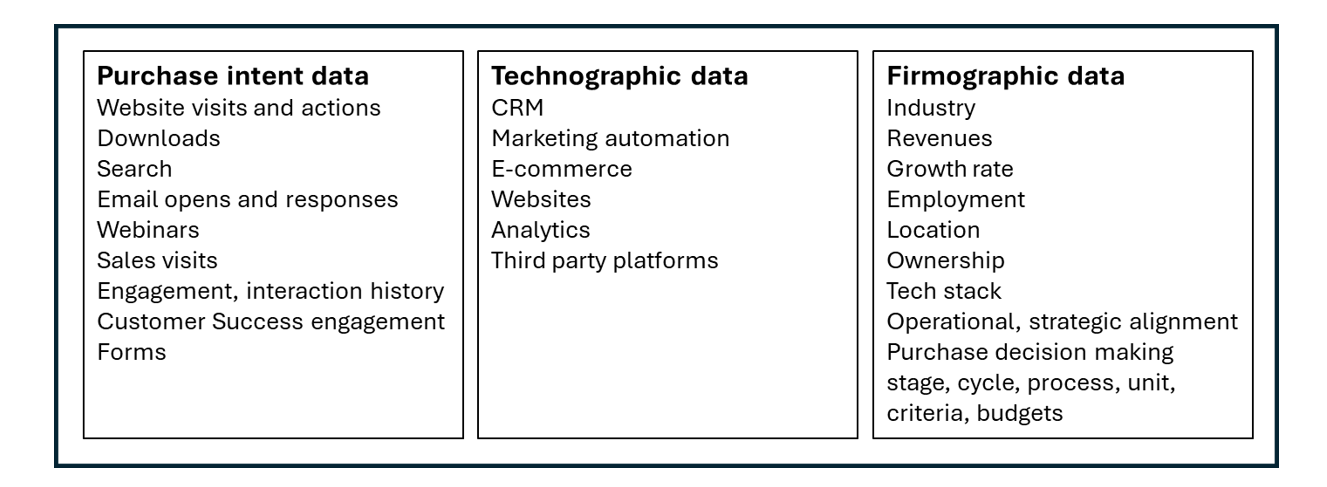

The “right customer” definition may draw on data from relationship marketing such as value (e.g., customer lifetime value), needs, behaviours, and influence (including in social media), as well as behavioural personas where the specific customer is not known but may still be categorized. Companies like Amazon do this when they associate your purchase behaviour with personas, which they then run through an algorithm to give you information such as “people who bought this, also bought that.” Somebody who opens an email in response to a specific message, or someone who attends a webinar, completes a form, or downloads a resource can similarly be categorized, especially if other information is available to combine with these actions. In the case of a B2B firm, inputs to the ICP definition could include purchase intent data such as stage in the customer’s journey, technographic data that matters for a specific business developing the ICP, and firmographic data, which may be likened to the B2B equivalent of demographics for consumer markets. Technographics includes the technology infrastructure of the customer, including the age and nature of their tech stack and gaps in it. Firmographics includes the nature and scale of the opportunity, the industry vertical, the size of the company, the type of ownership, the geographic location, the markets served, the cultural and operational alignment, the financial performance, the strategic challenges, the purchase decision-making unit and process, the vendor and solution selection criteria, and the customer’s position, seniority, and role within the purchase decision-making unit.

Having identified the ICP or ICPs, CBM next prioritizes signals and takes action to supplement and complement account-based marketing. We have identified examples of the kinds of signals for which a firm might search, but from where are these signals to come? Sales and customer success functions will surface buying signals as part of their engagement with prospects and existing customers. For many companies, the larger and often not fully realized opportunity lies in the signals from sources not typically managed by the firm, such as visits by prospects to the websites of competitors, or customers not on the firm’s current prospect list.

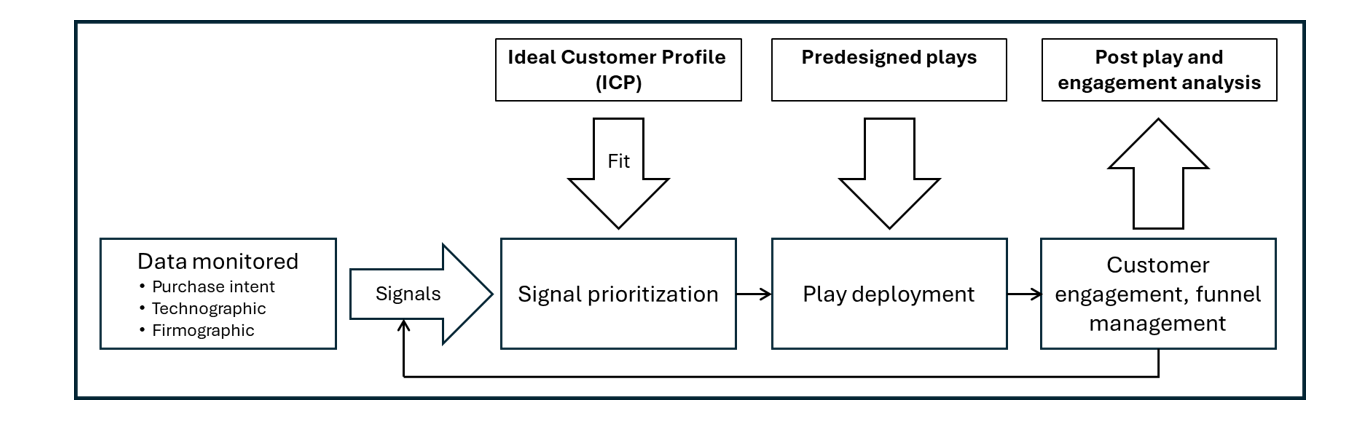

Figure 1 provides a flowchart of the main elements of CBM and the overall process, while Figures 2 and 3 provide more detail concerning the main components described in Figure 1: the data categories monitored for signals, the ICP, predesigned plays and post play and engagement analysis.

Figure 1: Contact-Based Marketing

Figure 2: Examples of data categories to be monitored

Figure 3: Ideal Customer Profile (ICP), Pre-designed plays and Post play and engagement analysis

Here’s an example.

You observe that a prospect has downloaded product specifications from your website and reviewed a product demonstration. That’s the trigger. The prospect aligns with the ICP according to the rules you have in place, and a play is auto-deployed to engage the prospect. An email is sent automatically to note their product interest and ask if any additional information is needed. An additional ask might be for a brief telephone meeting or an opportunity to demonstrate the product in person or at a distance. If there is no email reply, a second email is sent. If there is still no reply, a sales representative might reach out to connect on LinkedIn and call after a few days to follow up. If communication remains elusive, the prospect is kept warm by sending additional assets such as new videos, case studies incorporating validation by other accounts, and business cases showing ROI. The prospect is invited to a virtual town hall meeting with senior executives of the company where product plans are to be discussed. If there remains no expression of interest, the prospect is placed in a cold prospect loop and engaged periodically with marketing communications appropriate for their industry. If there has been a connection, the prospect is fed into the sales funnel and managed accordingly. Results are tracked and adjustments are made for the deployment of future plays with other prospects.

Technology for CBM

There are many technology options to provide and act upon these data. The following provides a brief list; this is necessarily partial—there are many companies in these spaces and I have necessarily been selective. Additionally, any list may have a relatively short life as the landscape of these tech marketplaces is changing rapidly, and firms obviously develop new solutions and discontinue others. Given these caveats, the reader might want to explore companies’ solutions that fall under the following categories:

- Purchase intent signals, such as opportunities for new business or growth within existing customers. Two of the companies of note here are Bombora and Unify. Bombora monitors millions of domains and billions of transactions on these domains as it looks for companies conducting research to surface their purchase intent and to enable progression thereof. Unify looks for additional signals by “tracking new hires, job changes, email intent” according to the firm’s website. The firm also enables users to execute “plays,” which are preplanned approaches based on specific signals that have been prioritized for action.

- Customer data platforms (CDPs) to build a single and integrated customer database that incorporates multiple signals from various sources to facilitate analysis and then action such as by email to individuals or advertising to specific audiences. Among the options here is Segment CDP.

- Accelerating internal responsiveness to make sure that prioritized signals from targeted ICPs are acted upon in a timely manner. A signal that is no longer fresh is no longer useful. One of the more frequently used platforms in this space is Slack, a technology platform used for passing time-sensitive information to the right sales personnel.

- Connecting with prospects using platforms from companies such as Apollo and Outreach to find prospects, engage with them, and measure the results of engagement. Clay provides tools that enable a firm to draw in data from multiple sources such as LinkedIn, Clearbit, and ZoomInfo (which itself has a large database and many tools) and then act on pre-determined signals autonomously, with marketing communications personalized at scale. Vector offers the ability to find prospects from the company’s website and elsewhere and engage with them based on pre-determined plays.

- Revenue orchestration to keep track of multiple inputs from sources such as CRM, marketing automation, and sales engagement to provide a single real-time view of the customer’s interactions and transactions. Examples of firms in this space include 6sense, Demandbase, Salesloft, LeanData, HubSpot, and Cadence. 6sense and Demandbase focus on account-based management, while the other firms may be more tailored to specific areas such as sales engagement, CRM, marketing automation, and analytics.

We have seen that CBM offers many businesses a new approach to accelerate revenue growth by monitoring and responding to the behavioural signals that are available in cyberspace, at least for anyone diligent enough to look while monitoring and responding to buying signals that prospects and customers may provide in the course of being managed by the sales and customer success functions. A B2B relationship marketing strategy focuses on the development of trust, operational and strategic alignment, and innovation as cornerstones of mutual value creation in the long term. The sales function pays close attention to moving customers through the sales funnel as expeditiously as possible. Customer success prioritizes customer retention and engagement. There remains a gap for companies to fill—finding customers who have exhibited some interest or purchase intent, engaging with them, and motivating purchase in the near term. This is the territory of CBM and for the CRO and CSO to manage. Planned with care, CBM complements other activities and roles such as those just mentioned by prioritizing short-term results while contributing to the formation of new relationships and maintaining existing ones over the long term.

Signals can come from many sources, as we have seen. They can be extracted and assessed for purchase intent. They can be fed into predictive modelling engines. AI and other platforms can manage them and communicate with individual customers at scale. Software agents can now even remove humans from the loop to make the process more expeditious and efficient. CBM is rising. The signals are there for us to see and hear, understand, and act upon—if we are watching and listening, that is.

About Author

Ian Gordon is a marketing management consultant and principal at Convergence Management Consultants Ltd., where he specializes in helping companies manage customer relationships and solve strategic marketing issues. He is the author of four marketing texts, including Relationship Marketing, Managing the New Customer Relationship, and Competitor Targeting, and 15 articles in Ivey Business Journal. He is an electrical engineer and marketer who has worked extensively at the intersection of marketing and technology as a consultant, executive, lecturer, and author. Contact: igordon@converge.ca