The competitive environment for global technology-driven companies has never been more intense. Quite clearly, these companies will invest heavily in new, exciting technologies over the long term. It is also clear that the bases on which these companies compete and differentiate are changing radically. In many situations, product differentiation is giving way to service differentiation and the integration of product-service packages as the basis for competitive differentiation. As a result, many companies that have traditionally been driven by product-centric strategies have shifted their focus to service and product-service-centric strategies. But making this change can prove disastrous, unless managers ask themselves the right questions. In this article, I will help managers ensure that the questions they do ask are the right ones.

MAKING THE TRANSITION: GENERAL ELECTRIC AND IBM

Two of the world’s best-known companies, General Electric and IBM, are in the midst of making the transition to a product-service-centric organization. But, GE and IBM, which are also two of the world’s best-managed companies, are, in fact, struggling to make this transition, only underlining the scale and scope of the challenge that managers face.

General Electric

The following excerpt from a BusinessWeek magazine article summarizes GE’s experience. “It started out simply enough. For years, General Electric sold CAT scanners, magnetic resonance imagers and other medical imaging equipment to the 300-plus hospitals run by health-care giant Columbia/HCA Healthcare Corp. In March 1995, GE persuaded Columbia to let it service all of the chain’s imaging equipment, including that made by GE’s rivals. Earlier this year, it added the management of virtually all medical supplies to the deal, most of them product lines GE isn’t even in.

“But the pièce de résistance was still to come. As the new contract took effect, Columbia invited a team of GE managers to help improve the way it runs hospitals. GE is now providing Columbia with a big dose of its well-known management skills. From GE’s fabled “workouts” to seminars on supply-chain management and employee training, GE executives are working with Columbia to boost productivity.

“For Columbia, which has saved tens of millions of dollars, it was medicine well worth swallowing. But for GE, the benefits go well beyond added revenue. The open-ended relationship is a smart gambit for gaining a greater lock on one of its biggest customers. It is also a sign of a profound shift now gaining steam at the world’s most successful conglomerate. Faced with slow domestic growth and cutthroat pricing abroad for its big-ticket manufactured items, GE’s Chairman and CEO John F. Welch is once again successfully transforming the global giant.” (BusinessWeek, October 23, 1996).

General Electric’s new CEO, Jeffrey Immelt, faces the formidable challenge of building and implementing this high-growth, integrated product-service strategy across several GE businesses.

Today, General Electric Medical Systems has undergone an extensive transformation from a product-centric business to a product-service hybrid. Once, services were provided and managed as a necessary cost centre. Now, GE Medical Systems is undergoing a complex and difficult transition to a company that provides a wide range of services, including operating radiological floors in hospitals. In making this transition, GE has encountered a number of major problems in managing the business and sustaining competitive differentiation and cash flow.

GE Aircraft Engine is undertaking a similar transition. It was formerly a product-centric company that sold aircraft engines to major airframe manufacturers; it carried on its service operation as a separate, cost-centred organization. In the last several years, it has become evident that the services surrounding aircraft operation are a potential tool for competitive differentiation and a source of enormous cash flow. As a result, GE is making an exciting strategic transition to capitalize on these opportunities.

IBM

Another company that is trying to implement an integrated product-service strategy is IBM. “IBM services now matter more than its hardware. That’s the key to Lou Gerstner’s remarkable turnaround in IBM’s future. In 1992, income from services represented 12 percent of IBM’s revenues; by 2003, it is estimated that services will represent 46 percent of revenues. The challenge facing IBM in moving to a product-service-centric organization is in managing the transition effectively.” (Fortune, April 26, 1999).

One Canadian company making the transition is Research In Motion, which makes components for the wireless business, and which had a history of being a product-centric company. Today, it is moving to become a product-services business by producing a small wireless device for receiving and sending e-mail, BlackBerry. Moving from a product-centric to a product-service-centric company has presented Research In Motion with major challenges. For example, it has no experience in retailing, and limited resources in a rapidly changing customer environment.

TECHNOLOGIES, PRODUCTS AND SERVICES: STRATEGIC PATHS

Strategic paths refer to the critical competitive spaces that define the opportunity a company has to transform itself and dictate which product/market strategy it should follow to achieve that transformation. (For a full description of strategic paths, see Winning Market Leadership, Ryans, More et al, Wiley and Sons, 2000) These spaces are highly interdependent and choosing one will have an impact on the others. For example, changing technology will change functionality. Each space also represents the competitive position that a company will occupy after making certain strategic choices.

There are four strategic spaces:

1. Technologies space

The concept of “technology” can be an ambiguous one. In this article, however, “technology” refers to physical phenomena, not the functionality a technology offers the customer. Some examples of physical technologies are superconductivity (motors) and fuel cells (cars). It is important to note that technologies such as these are useless by themselves, until they are transformed into differentiated product-service functions for specific customer segments.

2. Product-service functionalities space

Product-service functionalities are diff e rent from technologies in that they describe, according to a customer’s perception, those functions that will have value for the end-user. Product functionality refers to the application of a technology in combination with others for a particular customer. Service functionality describes the range of services that a supplier of the product functionality can offer independently, or with the product, to enhance its differentiation and competitive position. ResearchInMotion’s BlackBerry device is an example of product-service functionality.

3. End-user segments space

End-user segments refers to the group of customers who will ultimately use the particular product-service functionalities. In any competitive situation, there are a myriad of ways to segment end-user markets. Deciding which customer segments to pursue is driven by two major considerations:

- Compete for end-user segments which will allow you to achieve significant differentiation and customer choice

- Compete for end-user segments in which that customer choice can be translated into high, long-term positive net cash flow.

4. Market chains/networks space

Market chains/networks space represents the companies that are involved in every step of delivering product-service functionality to the end-user. Each company in the market chain can play a vital role in adopting a specific technology and product-service functionality. A simplified example of a generic market chain is shown in Figure 1. In reality, market chains can become very complex, and often look more like complex networks that are difficult to conceptualize and manage. The choice of market chains is often a difficult one, and it changes drastically with different product-service strategic paths.

PRODUCT-SERVICE COMPETITIVE SPACE

Products and services, and their product-service combinations, represent very different spaces in which companies can choose to compete. It is important to differentiate between products and services clearly, as well as their relationships. Doing so will dictate where a company chooses to compete rather than simply define what its products and services are.

Companies can choose to have a product-centric strategy, a service-centric strategy or a product-service strategy. Each can be different, according to the strategic path the company chooses.

Product-centric

A range of product-centric strategies is shown in Figure 2. Positioning certain products in strategic spaces can be very simple, while for others, such as nuclear reactors, it can be extraordinarily complex. A company can choose to compete and establish its profitability by positioning itself only in the product space. For example, a PC manufacturer can position itself as product-centric and not get involved at all with the service and maintenance surrounding a PC. A product-centric strategy doesn’t mean that the company isn’t involved in service issues such as warranties and various guarantees. It means that it is not positioned to compete on the basis of differentiating that service component, or to derive significant cash flow from it.

Service-centric space

A range of service-centric strategies is also shown in Figure 2. Specific companies can choose to compete solely on the service dimension without manufacturing the product. As the complexity of the product and service increases, however, the product and service tend to get “bundled.” In the end, many companies choose to compete in the service-centric space. In the auto industry, independent service garages compete with product-service-integrated car dealerships. In the medical equipment industry, many companies only service the equipment. The issue is not whether it makes sense to have a product-or service-centric strategy, but rather whether it is possible to be competitive and generate positive net cash flow.

Product-service space

The newest and fastest-growing competitive space is the product-service space. It is occupied by companies that position themselves as integrated product-service providers. For example, many PC companies such as IBM and Compaq market PCs, and have extensive service organizations to extend the use of the product. Many car dealerships have fully integrated sales and service operations where they try to maintain a relationship with customers, and the cash flow around servicing their cars over the lifetime of the vehicle. As products become more complex, companies tend to get drawn into the product-service space in terms of servicing the product and the importance of service excellence to the continued operation of the product. This is true of GE Medical Imaging. In the case of nuclear reactors, manufacturers almost have to be involved in servicing to protect themselves from liability.

MAPPING THE PRODUCT-SERVICE SPACES

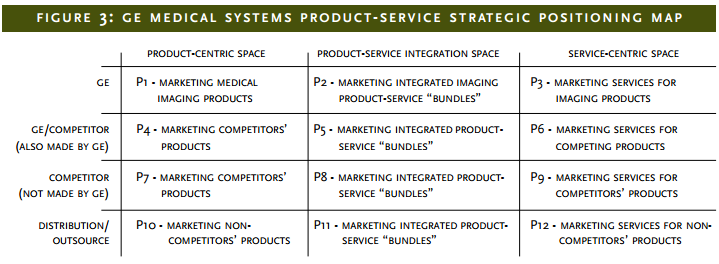

It is clear that companies considering their options for positioning themselves as product-service providers have many complex choices. As shown in Figure 3, companies can choose from at least 12 distinct competitive positions. They can compete in one or more of these positions, and indeed can move from one to another over time. The thrust of this paper is to explore which position makes sense for a particular situation, what critical conditions must exist for a company to compete in each area and for it to move from one position to another. Two dimensions of this map are featured, product-service positioning and competitive positioning.

Product-service position

In Figure 3, a product-service position is described as one with three strategic choices: competing in a product-centric space; competing in a services-centric space; or competing in a product-service integrated space.

Competitive position

In Figure 3, “competitive position” describes the nature of the product-service strategy in competitive terms. There are four distinct positions that a company can occupy:

1. Company position: A company that competes in product or service situations involving only products or services that it manufactures or delivers itself.

2. Company/competitor position: A company that competes in product and service markets where it markets not only its own products or services, but also those of competitors that compete directly with its own.

3. Competitor position: A company that competes with products or services that it doesn’t produce but are nevertheless in the same product and service space in which it competes.

4. Distribution/outsource position: A company that provides products and services that it does not produce but rather distributes.

These 12 distinct competitive spaces represent an exciting array of strategic choices for competing companies, and more importantly, a wide array of potential strategic paths over time.

GE medical systems

GE Medical Systems is an outstanding example of a company trying to make a challenging transition from a product-centric company to one of the other strategic paths. The basic strategic-path dimensions for GE are shown in Figure 4.

Technologies space

General Electric Medical Imaging employs a wide range of complex technologies. It is an innovative world leader that invests heavily in new imaging technologies, and is constantly adding and researching new technologies.

PRODUCT-SERVICE FUNCTIONALITY SPACE

GE has a wide range of product-service functionality dimensions in its strategy. Scanning functionality includes CAT scanning, x-ray scanning, magnetic resonance and tomography, as well as nuclear-scanning devices. All of these reveal a variety of symptoms and causes that are otherwise difficult to detect and understand. It also offers a wide range of services, including financing, patient management, logistics planning, equipment planning, staff, maintenance, parts and training.

End-user segments space

End-use customers for medical imaging include medical clinics, teaching hospitals and various treatment centres.

Market chains/networks space

There is a complex set of market chains and networks related to these end-users, such as other product and service companies, HMOs, physicians, and various other organizations that provide a wide range of products and services to the medical community. Clearly, the strategic paths that GE Medical Imaging is following are very complex, and it needs to identify those could that be the most profitable in the long term.

MAKING THE RIGHT CHOICES

It isn’t clear that any particular path or set of paths will be more profitable than another. However, it is critical that the choice of paths remain clear at any point in time, and that the basis for long-term positive net cash flow be clearly established. Figure 3 shows 12 different strategic paths that GE could take; it could take one of these paths or, for that matter, all 12. It is critical that planning the transitional path from the product-centric path to other positions is done with great care. Looking at Figure 3, we can visualize the choices GE has as a product-centric medical imaging company.

Product-centric strategic path

GE’s initial product-centric strategic path is shown by a strategy that combines the marketing of medical imaging products made by GE and the marketing of services for GE-specific imaging products (P1 + P3 in Figure 3). This is a traditional position and one that is still occupied by many competitors. In this position, the major activity occurs in the product-centric position (P1), marketing products that are manufactured by General Electric. The service-centric position (P3) provides the services for those products produced by GE for conditions of warranty or liability, and all of the factors that make it necessary to carefully service medical imaging equipment. In GE’s case, services were conceptualized as a cost centre.

From product-centric to product-services integration

Looking at Figure 3, this strategic path describes the transition from (P1 + P3) to (P2), in which GE markets an integrated product-service bundle that it can manufacture itself. This is a very different position from (P1 + P3).

From product-centric to company competitor and services-centric

This strategic path is very different from the previous one. In this situation, going from (P1 + P3) to (P2 + P5) GE goes from marketing its own medical imaging products and servicing them as a separate service-centric cost centre, to marketing competitors’ products that are also made by GE. With this strategy, GE offers customers the full choice of both its own products and competing products and services. One of the challenges facing GE is how it should manage the myriad of choices. A critical issue in considering these choices is the generation of positive and negative cash flows that will result from a particular strategy. Understanding these cash flow dynamics has been a major challenge for GE.

CRITICAL STRATEGIC CHOICES

In looking at product-service integration, a significant number of very difficult strategic choices have to be made on factors such as:

- Pricing products and services

- Product-service positioning and bundling

- Competitor relationships

- Warranties

- Customer relationship management

- Target customers and segments

- Market chains, networks and margins

- Logistical materials management, and supplier relationships

- Cost-behaviour and management

- Resource allocation

All of these strategic choices are very diff e rent, depending on the objectives a company has for product-service integration and how it sees the choices it makes working together.

CONSTRAINTS ON PRODUCT-SERVICE INTEGRATION

In companies like GE, there are serious obstacles to the effective integration of products and services. A major stumbling block can be a lack of clarity on the objectives of product-service integration. This presents a management challenge because the temptation is there to manage products and services separately. They are often different parts of the organization, with separate and different cost infrastructures. They frequently have different and separate customer segments, pricing methodologies, channels of distribution and market chains, and corporate and individual performance metrics. For all of these reasons, the challenge of managing them clearly is a very difficult one.

PERFORMING A POWERFUL PRODUCT-SERVICE INTEGRATION ANALYSIS

Implementing an integrated pro duct-service strategy is a major challenge. However, management teams that follow the stages outlined below will feel more confident in facing that challenge. These stages are shown schematically in Figure 5.

- Define current strategic paths

- Analyze cash flow performance of current strategic paths

- Identify an attractive product-service transitional path

- Analyze product-service strategic-path synergies

- Estimate the impact on cash flow of changes in the product-service strategic path

- Identify the major forces and barriers to success in strategic-path transition

- Outline a transitional path strategy.

By going through these stages iteratively, a management team can come to grips with the critical questions and issues that must be resolved in changing its product-service strategy.