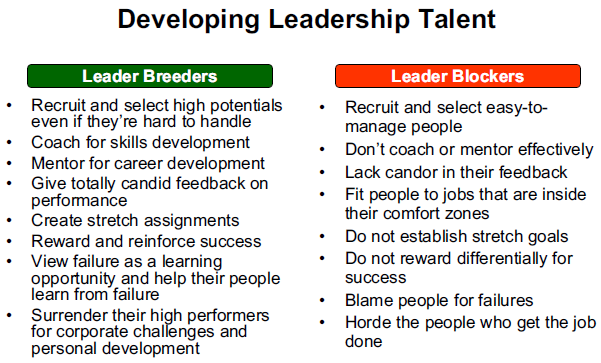

One trait that makes a leader great is his or her ability to hire and mentor high-potential individuals. Enter the leader breeder, who, unlike the leader blocker, has the emotional intelligence and uncanny sense required to attract, develop and retain talent, regardless of their academic background. This Ivey professor and leadership expert describes who these leader breeders are and how they contribute to highperforming organizations.

Increasing attention is being paid to how well executives develop tomorrow’s leaders. Put simply, the executive who is a leader-breeder is much more valuable than one who is a leader-blocker. So, what is it that these “leaderbreeders” actually do? This article will answer this important question.

Recruit high potentials

Leader breeders recruit high potentials, even if they are hard to handle. They don’t go for the safe, conventional hires. McKinsey & Co., for example, will hire people with first-class degrees from top universities, whether or not they have degrees in business. These people are unlikely to have the same thought processes as MBAs, something that will probably lead to longer meetings, greater difficulty in achieving consensus, and require more training and development. However, it will pay off in greater diversity of thought and higher quality solutions — which is the McKinsey product.

In order to recruit high potentials consistently, leaders must know the aptitudes — the inherent, natural characteristics of individuals — that correlate with high performance. These may be cognitive characteristics, dimensions of personality, or other natural talents that will become extraordinary ability with the right kind of developmental experiences. But they must also know the kinds of rewards that candidates are looking for and whether or not they can realistically provide them. Over time, good leaders will find out where to search for such people, how to attract them, how to sort out the true high potentials from those who have learned to deceive an interviewer or fake-out some simple paper-and-pencil test.

A leader-breeder is not put off by energetic, creative, talented people who don’t look like everyone else or think along conventional lines or speak in conventionally polite forms. Naivety doesn’t bother them, neither does lack of conformity, or even some arrogance. Naivety is often associated with clear thinking, non-conformity with creativity and arrogance with self-confidence. Each can be worked on if the leader is prepared to mentor and coach the acolyte.

Coach for competencies

Leader-breeders know the essential competencies that high-potentials need to be effective in their roles and get ahead in the organization. There are many generic leadership competencies and even more that may be specific to an organization, role or corporate culture. They model those behaviors themselves or, if they lack them, are willing to ‘fess up to their own deficiencies, emphasize the need for them, and either try to acquire them or build compensating mechanisms through the composition of their teams. The leader-breeder generally has some degree of humility and self-awareness and yet the confidence to coach others. They are more than willing to link high-potentials to other leaders who exhibit the required competencies. The coach does not have to dominate the relationship.

This coaching is ongoing, not just in formal performance-management sessions; also, it is true coaching not teaching or training. These coaches know what competencies are needed for success. They keenly observe their people, learn what turns them on and turns them off, look for their natural strengths and weaknesses, work on the former so that strengths lead to excellence and on weaknesses so that they become adequate, and encourage them to strive for personal bests.

Great coaches are great sensors. They understand what makes the person tick, what their natural aptitudes are and what needs to be taught. They understand that they must motivate people with high natural ability in order to get high performance and that such performance will not come without a clear sense of direction and the resources to enable it. They understand that the task of the coach is often to “round the edges” of assertive high-potentials, without dulling them.

Mentor for career development

Leader breeders are mentors. While competencies are critical to performance in a role, more is needed to help people advance in their careers. Most organizations have key values that they expect their leaders to exhibit and have a keen sense about what behaviors are appropriate under different circumstances.

There are taboos in organizations, and potential leaders must know what they are and when they are transgressing. There are highly political issues that must be handled very delicately, without appearing to be a political animal, just as there are unwritten rules and regulations that people need to know about. The fact that a chairman of a certain bank was the only one who used a red pencil, whereas the president used a green one, was not known to the young leader-wannabe who marked up a document for onward transmission in one of the reserved colors. The young executive who transgressed by telling off-colour stories at a management meeting, who was involved in a personal relationship with an assistant in an organization which frowned on such relationships, who used inappropriate language, who was not deferential to statusconscious colleagues…may sound like small potatoes. But the fact is that all of these behaviours impaired theeffectiveness of these leadership neophytes. The mentor spots these missteps and brings them to the attention of the leader-to-be so that they can be addressed.

Mentors are people to whom the unsure, the inexperienced, the perplexed or the puzzled can turn for advice, interpretations and guidance. There may be an issue where someone needs to talk over some ethical concerns, the offer of a job positing or career move where someone is unsure whether it is right for them, or some uncertainty about the way ahead.

Mentoring can be initiated and requested by either someone requiring it or someone who offers it when she or he thinks that it is needed. But it can seldom be forced on either the giver or the receiver. Mentoring requires the establishment of a trusting relationship — the mentor will be seen as someone genuinely wanting to help the less experienced person while he or she, in turn, will be genuinely seeking advice and assistance.

Give candid feedback

Leader breeders give candid feedback. They don’t round corners or try to cushion critical feedback by wrapping it up in vague comments about how good the performance has been in the past or in dimensions other than the one that is being focused on. They don’t follow some of the accepted wisdoms such as bracketing negative feedback with positive comments, using only positive reinforcement, and so on.

Those leaders who do this are not afraid that they will disable the performance of those to whom they give candid feedback; nor are they concerned that those to whom they give great feedback will somehow become less effective because of it. This is because this feedback is accompanied by coaching and mentoring and, as described below, sincere efforts to learn from failure. Swell-headedness can usually be controlled by reminding high potentials that the one sure way to fail to achieve the high potential is by behaving as if you are one!

Candid feedback does not have to be cruel feedback. Where it addresses basic aptitude deficiencies, people sometimes worry that it may be perceived as an attack on the person. As a result, they would rather not have this direct, difficult conversation. But, when the effort is accompanied by a genuine desire to see the person succeed at something which is more compatible with their basic inherent capabilities, giving the feedback can be constructive. I hold no rancor towards the professor who failed me out of medical school some 40 years ago, thereby doing a favor to the human race and redirecting me toward something for which I was better suited.

Create stretch assignments

Good leaders encourage people to stretch themselves. You don’t get the most from people by putting them on the rack and stretching them…you get more when they raise their own aspirations and use their own energy and frustration as drivers of increased performance.

Many organizations stretch people, sometimes to the point of breaking them. Even if they fall short of this, they may take some pleasure in forcing them to set unattainable targets in the belief that they will somehow do better if they chased the impossible dream. Many times this sort of pressure results in totally inappropriate behavior — the decision to book revenue when it is not certain, to postpone safety-related maintenance rather than incur a cost in a certain accounting period, to dump waste rather than have it recycled, or to put pressure on your people to the point where they start to disengage from the organization even while they appear to be pursuing stretch goals.

Good leaders just don’t do this. They recognize that inexperienced high-potentials will tend toward establishing unrealistic targets and may lose perspective as they strive to achieve them. They are there — as coaches and mentors — to help them recognize these dangers and exercise the appropriate degree of self-control. This is the process whereby many high-potentials develop that critical dimension of executive performance…judgment.

This stretch may come at some risk to the leader who encourages it. I remember vividly the two product managers who were determined to develop and present their own product plans and, three days before the due date, did not have them done. I would have taken the responsibility for “mission not accomplished” and I admit, belatedly and a little shamefacedly, to having had a contingency plan in place in the form of my own draft plans to be used in the event that they did not perform. But they came through in the end…perhaps not as well as I thought, rightly or wrongly, might have been done but sufficiently well that I was able to coach them to what I considered higher performance shortly after the due date.

Reward and reinforce success

Leader-breeders reward and reinforce success. High potentials who are also high performers invariably have high needs for recognition and rewards, the latter because they are the tangible manifestation of recognition. Failure to reward people who achieve differentially from those who don’t is simply unacceptable to high achievers. This is true even if the task is “team effort.” Those who see themselves as high achievers demand that the team leaders differentiate between the relative contributions of team members — sometimes a difficult thing to do.

Leader-breeders take the rewards that they have to offer and distribute them according to merit. If the average pay raise for a division is four percent, they don’t give the best five percent and the worst three percent. They will give the best 10 percent…or more, the next best less, but still much more than the average. Of course this can only be done by if some are paid very substantially below the average. Such leaders are prepared to do this.

But monetary rewards are only part of the reward picture. High performers are given many more opportunities than the average. They are given greater challenges, greater chances for development, interesting projects on which to work, and the opportunity for exposure to more senior levels of management.

More and more companies are recognizing this need for differentiation and are developing performance management and reward systems that demand it. Whether through forced ranking, bell-curving appraisals and rewards, top-grading or other mechanisms, distinctions are being made between top performers and those who are not. And once these distinctions have been made, managers are expected to act accordingly.

Treat failure as learning

Leader breeders hate to fail — but they also learn to treat failure as a learning experience. With greater challenge comes greater risk of failure. High potentials, setting stretch goals, are going to fail and it is how that failure is addressed that will make a difference in developing leaders.

Where failure is punished or blame is thrown around, little is learned. People get defensive, they avoid setting stretch goals, and play in their personal safety zones. Someone once described such an environment to me: “This place is like a marine boot camp. If you stick your head above the foxhole you get it shot off; if you keep it down you get it s–t on.” Learning does not take place in such an environment and learners are not attracted to it.

Contrast this with the post-surgical conference that takes place when a patient passes away or to the productwithdrawal process that used to operate at the pharmaceutical firm I used to work for many years ago. Here we had to write a “reverse marketing plan” explaining why the product was being taken off the market. This often involved analyzing what went wrong with the plan that had been written to justify its launch. There was no blame thrown around; the assumptions leading to the marketing decision were identified and checked against actual events. The question was always “Why did we err?”, rather than “Who erred?” And the outcome was learning and improvement. The founder of IBM, Thomas J. Watson, Jr., was famous for dissecting the errors made by his executives and then, rather than firing them — as they expected — moving them to new assignments, with some comment about the Company having made a considerable investment in their education.

There are, of course, some limits to “failure as learning.” Smart people are not expected to make the same mistake twice; fatal errors tend to attract more blame than those that result in less drastic consequences; and failures that identify personally unacceptable behaviours such as laziness, carelessness, lack of integrity, or personally self-serving behaviours tend to be treated differently. This is acceptable within a leadership development culture.

Leader breeders surrender their high performers for development

Leader breeders don’t horde their talent, using them to deliver performance now at the expense of their development for the future. Hoarding talent is the most understandable of events — after all, the boss has often made a considerable investment in the development of a certain individual and wants to get some return on that investment. Also, the case can be made that having this individual operating at full capability benefits the organization and having people move on as soon as they become fully competent is detrimental to the organization.

Sound judgement must be exercised when planning the pace of change for individuals on developmental tracks. People need to have the experience of learning how to do something and then actually doing it — living with the consequences, good and bad. However, to stay beyond the point where the experience does not lead to further learning is a waste of potential talent.

The best leader-breeders are always conscious of this trade-off and stay in touch with their talent pools to ensure that development is continuing to take place. When it’s not, they will aggressively intervene to ensure that the developmental opportunities keep coming their way. They will happily, if sometimes a little ruefully, carry the badge of being “talent exporters” to the rest of the organization. Many believe that this is more than off-set by the fact that those who do this attract other great talent to work for them, bringing fresh energy and perspective that leads to even better performance.

There are many challenges facing the organization that seeks to develop leadership bench strength. They must find out where great talent lives, attract, recruit, develop, deploy, and retain it. The leader-breeders in the organization make these things happen; the leader-blockers prevent them from developing. The leader-breeders have a multiplier-effect on leadership development…they are worth some multiple of their own leadership skills, with this multiple being reflected in the aggregate leadership strength in the organization. Increasingly, these leader breeders are being recognized in organizations and are being rewarded accordingly. Are you one of them?