Mix sustainable development, corporate social responsibility, stakeholder theory and accountability, and you have the four pillars of corporate sustainability. It’s an evolving concept that managers are adopting as an alternative to the traditional growth and profit-maximization model.

In recent years there has been significant discussion in the business, academic, and popular press about “corporate sustainability.” This term is often used in conjunction with, and in some cases as a synonym for, other terms such as “sustainable development” and “corporate social responsibility.” But what is corporate sustainability, how does it relate to these other terms, and why is it important? This paper addresses these questions.

What is corporate sustainability?

Corporate sustainability can be viewed as a new and evolving corporate management paradigm. The term ‘paradigm’ is used deliberately, in that corporate sustainability is an alternative to the traditional growth and profit-maximization model. While corporate sustainability recognizes that corporate growth and profitability are important, it also requires the corporation to pursue societal goals, specifically those relating to sustainable development — environmental protection, social justice and equity, and economic development.

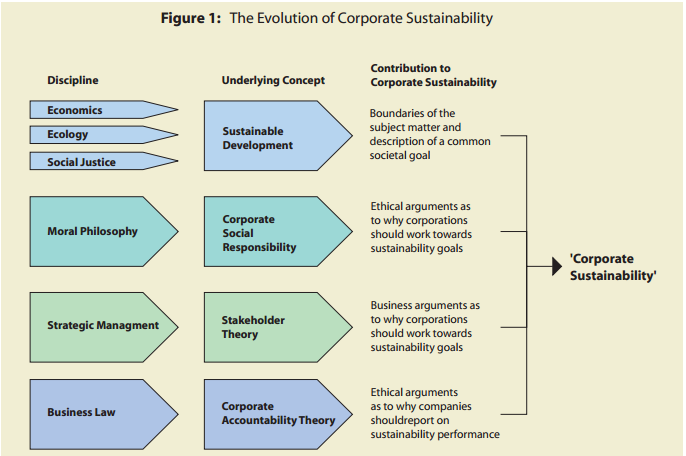

A review of the literature suggests that the concept of corporate sustainability borrows elements from four more established concepts: 1) sustainable development, 2) corporate social responsibility, 3) stakeholder theory, and 4) corporate accountability theory. The contributions of these four concepts are illustrated in Figure 1. Each concept, and its relationship to corporate sustainability, is discussed below.

1) Sustainable Development

Sustainable development is a broad, dialectical concept that balances the need for economic growth with environmental protection and social equity. The term was first popularized in 1987, in Our Common Future, a book published by the World Commission for Environment and Development (WCED). The WCED described sustainable development as development that met the needs of present generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs. Or, as described in the book, it is “a process of change in which the exploitation of resources, the direction of investments, the orientation of technological development, and institutional change are all in harmony and enhance both current and future potential to meet human needs and aspirations.” Sustainable development is a broad concept in that it combines economics, social justice, environmental science and management, business management, politics and law. It is a dialectical concept in that, like justice, democracy, fairness, and other important societal concepts, it defies a concise analytical definition, although one can often point to examples that illustrate its principles.

In Our Common Future, (Oxford University Press, 1987) the WCED recognized that the achievement of sustainable development could not be simply left to government regulators and policy makers. It recognized that industry had a significant role to play. The authors argued that while corporations have always been the engines for economic development, they needed to be more proactive in balancing this drive with social equity and environmental protection, partly because they have been the cause of some of the unsustainable conditions, but also because they have access to the resources necessary to address the problems.

Industry’s response to the WCED’s call came in stages as everyone wrestled with what sustainable development in action should look like. The first serious sign of support came from the International Chamber of Commerce when it issued its Business Charter for Sustainable Development in 1990. This was followed in 1992 by the book Changing Course, by Stephen Schmidheiny and the Business Council for Sustainable Development (now the World Business Council for Sustainable Development; MIT Press, 1992). Both publications focused on the role of corporations in sustainable development, and the authors argued that supporting sustainable development was as much an economic necessity as it was an environmental and social necessity. Since then, many business leaders and corporations have come forward to show their support for the principles of sustainable development.

The contribution of sustainable development to corporate sustainability is twofold. First, it helps set out the areas that companies should focus on: environmental, social, and economic performance. Second, it provides a common societal goal for corporations, governments, and civil society to work toward: ecological, social, and economic sustainability. However, sustainable development by itself does not provide the necessary arguments for why companies should care about these issues. Those arguments come from corporate social responsibility and stakeholder theory.

2) Corporate social responsibility

Like sustainable development, corporate social responsibility (CSR) is also a broad, dialectical concept. In the most general terms, CSR deals with the role of business in society. Its basic premise is that corporate managers have an ethical obligation to consider and address the needs of society, not just to act solely in the interests of the shareholders or their own self-interest. In many ways CSR can be considered a debate, and what is usually in question is not whether corporate managers have an obligation to consider the needs of society, but the extent to which they should consider these needs.

As a concept, CSR has been around much longer than sustainable development or the other concepts discussed in this paper. A 1973 article by Nicholas Ebserstadt traced the history of CSR back to ancient Greece, when governing bodies set out rules of conduct for businessmen and merchants (Managing Corporate Social Responsibility, Little, Brown and Company, 1977). The role of business in society has been debated ever since. According to Archie B. Carroll, one of the most prolific authors on CSR, the modern era of CSR began with the publication of the book Social Responsibilities of the Businessman by Howard Bowen in 1953. Since then, many authors have written on the topic. For the first few decades after 1953, the main focus of these writings was whether corporate managers had an ethical responsibility to consider the needs of society. By 1980 it was generally agreed that corporate managers did have this ethical responsibility, and the focus changed to what CSR looked like in practice.

The arguments in favour of corporate managers having an ethical responsibility to society draw from four philosophical theories:

- Social contract theory. The central tenet of social contract theory is that society consists of a series of explicit and implicit contracts between individuals, organizations, and institutions. These contracts evolved so that exchanges could be made between parties in an environment of trust and harmony. According to social contract theory, corporations, as organizations, enter into these contracts with other members of society, and receive resources, goods, and societal approval to operate in exchange for good behaviour.

- Social justice theory. Social justice theory, which is a variation (and sometimes a contrasting view) of social contract theory, focuses on fairness and distributive justice— how, and according to what principles, society’s goods (here meaning wealth, power, and other intangibles) are distributed amongst the members of society. Proponents of social justice theory argue that a fair society is one in which the needs of all members of society are considered, not just those with power and wealth. As a result, corporate managers need to consider how these goods can be most appropriately distributed in society.

- Rights theory. Rights theory, not surprisingly, is concerned with the meaning of rights, including basic human rights and property rights. One argument in rights theory is that property rights should not override human rights. From a CSR perspective, this would mean that while shareholders of a corporation have certain property rights, this does not give them licence to override the basic human rights of employees, local community members, and other stakeholders.

- Deontological theory. Deontological theory deals with the belief that everyone, including corporate managers, has a moral duty to treat everyone else with respect, including listening and considering their needs. This is sometimes referred to as the “Golden Rule.”

CSR contributes to corporate sustainability by providing ethical arguments as to why corporate managers should work toward sustainable development: If society in general believes that sustainable development is a worthwhile goal, corporations have an ethical obligation to help society move in that direction.

3) Stakeholder theory

Stakeholder theory, which is short for stakeholder theory of the firm, is a relatively modern concept. It was first popularized by R. Edward Freeman in his 1984 book Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (Pitman Books, Boston, Mass, 1984). Freeman defined a stakeholder as “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives.” The basic premise of stakeholder theory is that the stronger your relationships are with other external parties, the easier it will be to meet your corporate business objectives; the worse your relationships, the harder it will be. Strong relationships with stakeholders are those based on trust, respect, and cooperation. Unlike CSR, which is largely a philosophical concept, stakeholder theory was originally, and is still primarily, a strategic management concept. The goal of stakeholder theory is to help corporations strengthen relationships with external groups in order to develop a competitive advantage.

One of the first challenges for companies is to identify their stakeholders. There appears to be general agreement among companies that certain groups are stakeholders — shareholders and investors, employees, customers, and suppliers. Beyond these, however, it becomes more challenging because there are no clear criteria for defining stakeholders. Most authors agree that if the term ‘stakeholder’ is to be meaningful, there must be some way of separating stakeholders from non-stakeholders. Some authors have suggested that stakeholders are those that have a stake in the company’s activities – something at risk. Other authors have suggested that if you consider the global impacts of industry – such as climate change or cultural changes due to marketing and advertising – everyone is a stakeholder. The issue of qualifying criteria for stakeholder status is currently being debated.

Assuming that the main stakeholders have been identified, the next challenge for corporate managers is to develop strategies for dealing with them. This is a challenge because different stakeholder groups can, and often do, have different goals, priorities, and demands. Shareholders and investors want optimum return on their investments; employees want safe workplaces, competitive salaries and job security; customers want quality goods and services at fair prices; local communities want community investment; regulators want full compliance with applicable regulations. However, there is a general acknowledgement that the goals of economic stability, environmental protection, and social justice are common across many stakeholder groups. Few groups would argue against these goals, although they may debate the level of priority or urgency.

The contribution of stakeholder theory to the corporate sustainability is the addition of business arguments as to why companies should work toward sustainable development. Stakeholder theory suggests that it is in the company’s own best economic interest to work in this direction because doing so will strengthen its relationship with stakeholders, which in turn will help the company meet its business objectives.

4) Corporate Accountability

The fourth and final concept underlying corporate sustainability is corporate accountability. Accountability is the legal or ethical responsibility to provide an account or reckoning of the actions for which one is held responsible. Accountability differs from responsibility in that the latter refers to one’s duty to act in a certain way, whereas accountability refers to one’s duty to explain, justify, or report on his or her actions.

In the corporate world, there are many different accountability relationships, but the relevant one in the context of this paper is the relationship between corporate management and shareholders. This relationship is based on the fiduciary model, which in turn is based on agency theory and agency law, wherein corporate management is the ‘agent’ and the shareholders the ‘principal’. This relationship can be viewed as a contract in which the principal entrusts the agent with capital and the agent is responsible for using that capital in the principal’s best interest. The agent is also held accountable by the principal for how that capital is used and the return on the investment.

Corporate accountability need not be restricted to the traditional fiduciary model, nor only to the relationship between corporate management and shareholders. Companies enter into contracts (both explicit and implicit) with other stakeholder groups as a matter of everyday business, and these contractual arrangements can serve as the basis for accountability relationships. For example, companies that receive environmental permits and approvals from regulators to operate facilities are often held accountable by the regulators for whether the terms of the approval are being met. Proponents of social contract theory often argue that corporations are given a ‘licence to operate’ by society in exchange for good behaviour, and as such the corporations should be accountable to society for their performance.

The contribution of corporate accountability theory to corporate sustainability is that it helps define the nature of the relationship between corporate managers and the rest of society. It also sets out the arguments as to why companies should report on their environmental, social, and economic performance, not just financial performance. In 1997, John Elkington of the UK consultancy, Sustain Ability, called this type of accounting on environmental, social, and economic performance as ‘triple bottom line’ reporting.

Corporate sustainability is a new and evolving corporate management paradigm. Although the concept acknowledges the need for profitability, it differs from the traditional growth and profit-maximization model in that it places a much greater emphasis on environmental, social, and economic performance, and the public reporting on this performance.

Corporate sustainability borrows elements from four other concepts. Sustainable development sets out the performance areas that companies should focus on, and also contributes the vision and societal goals that the corporation should work toward, namely environmental protection, social justice and equity, and economic development. Corporate social responsibility contributes ethical arguments and stakeholder theory provides business arguments as to why corporations should work towards these goals. Corporate accountability provides the rationale as to why companies should report to society on their performance in these areas.

Not all companies currently subscribe to the principles of corporate sustainability, and it is unlikely that all will, at least not voluntarily. However, a significant number of companies have made public commitments to environmental protection, social justice and equity, and economic development. Their number continues to grow. This trend will be reinforced if shareholders and other stakeholders support and reward companies that conduct their operations in the spirit of sustainability.