The imperative to build or buy has diminished considerably in the past few years, as chastened managers lick their wounds caused by failed acquisitions. But instead of a buying spree, managers are on a “bonding” spree, discovering, for all the right reasons, that alliances are a far more predictable – and manageable – engine for growth. And if the “marriage doesn’t work,” well.nothing ventured, nothing lost.

The imperative to build or buy has diminished considerably in the past few years, as chastened managers lick their wounds caused by failed acquisitions. But instead of a buying spree, managers are on a “bonding” spree, discovering, for all the right reasons, that alliances are a far more predictable – and manageable – engine for growth. And if the “marriage doesn’t work,” well.nothing ventured, nothing lost.

This is a condensed version of an article that will be published in the summer edition of the London Business School’s Business Review.

In May 2001, Matt Schifrin, editor of Forbes.com, wrote that, “Alliances may be the most powerful trend that has swept (global) business in the past 100 years. Strategic alliances are hot….” Fred Weston, UCLA professor and the former president of the American Finance Association, has noticed a dramatic rise in new joint venture announcements to rival mergers – a correlation of nearly 100 percent. And Peter F. Drucker, the father of modern management, is quoted as saying “there is not only a surge in alliances, but a worldwide restructuring for major corporations is occurring in the shape of alliances and partnerships.”

It would have been hard to find such enthusiasm for alliances five years ago. Then, most professional service firms and academics dismissed alliances as a fad. So then, what has happened in the last five years that have made alliances in general, and equity alliances, in particular, a strategic option?

In 2000, our firm published a paper, “The Next Wave of Alliance Formations: Forging Successful Partnerships with Emerging and Middle Market Companies.” This was essentially a primer on alliance formations, written from the perspective of inexperienced small to middle-market firms seeking to partner with large firms experienced and skilled in alliance formations and management. This article captures and describes the significant growth in alliance activity since 2000. In it, we examine perhaps the major phenomenon in the world of alliances today – the fact that equity alliances are taking center stage, and why major corporations are choosing the “bond” option over the “buy” or “build” options to stimulate growth and increase corporate wealth. We will also discuss the different types equity alliances and compare them with acquisitions in terms of wealth creation, revenue growth and probabilities of success. Finally, in the The Art of the Deal, we outline some best practices for forming and managing alliances.

What is an alliance?

A strategic alliance is an organizational and legal construct wherein “partners” are willing-in fact, motivated-to act in concert and share core competencies. To a greater or lesser degree, most alliances result in the virtual integration of the parties through partial equity ownership, through contracts that define rights, roles and responsibilities over a span of time or through the purchase of non-controlling equity interests. Many result eventually in integration through acquisition.

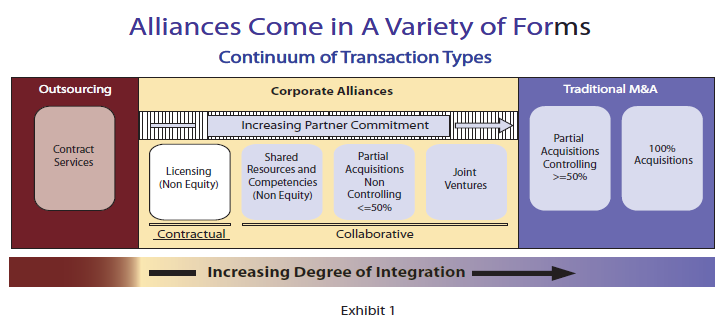

The fundamental purpose of an alliance is to facilitate collaboration and varying degrees of integration between companies without necessitating a merger or an acquisition, though it can often lead to a merger or an acquisition. Exhibit 1 reflects the full spectrum of the types of inter-corporate transactions arrayed by the level of commitment and degree of integration between the parties.

At the far left is outsourcing; at the opposite extreme is M&A. Corporate alliances lie in between. While many refer to their suppliers or customers as their “partners,” not every party that one conducts business with is a true partner, nor is every relationship a true alliance.

At the far left is outsourcing; at the opposite extreme is M&A. Corporate alliances lie in between. While many refer to their suppliers or customers as their “partners,” not every party that one conducts business with is a true partner, nor is every relationship a true alliance.

As the chart highlights, licensing is a contractual alliance with little collaboration. Collaborative alliances include shared resource arrangements, partial acquisitions and JVs. Pilot projects and R&D funding agreements, are typical examples of shared resource arrangements and competencies agreements. Although these collaborations start out as contractual, it is not uncommon for them to evolve into a more permanent equity-based structure.

Equity alliances can be classified into two general types: The first one is partial acquisitions, where a company purchases a minority equity stake in another, such as Viacom purchasing a 35 percent stake in Infinity Broadcasting). The second type is cross-equity transactions, where each partner becomes an equity stakeholder in the other, such as the exchange of shares between EDS and Ariba.

Next are joint ventures, of which there are two kinds, solution joint ventures and platform joint ventures. A solution joint venture is where two or more companies, usually of similar size or value, form a new entity to exploit a business opportunity that neither could do alone. The teaming up between GE Capital and BankOne to create Monogram Credit Services illustrates a solution joint venture.

A platform JV is one in which two or more partners realize that even together they are missing a critical core competency or competencies to meet their strategic cooperative objectives. In order to move quickly, they form a JV to purchase a company or a stake in a company that has the missing core competency. Platform alliances work best when the opportunity is very large and the window of time for exploitation is narrow. In other words, speed is of the essence. An example of a platform JV is the joint purchase of Midlands Electricity (UK) by General Public Utilities and Cinergy. It is important to note that just 750 equity alliances and joint ventures were formed in the U.S. throughout the 1970s. Now, however, thousands are formed annually in the U.S. alone. Exhibit 2 shows a number of examples of the various types of equity alliances

The emergence of equity alliances

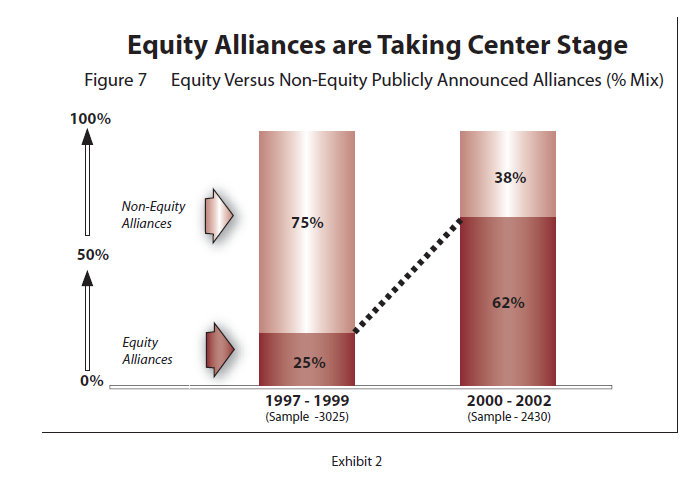

There has been a dramatic increase in equity-based alliances. Since 2000, the numbers of acquisitions has declined by 65 percent, while equity alliances have continued to grow. For example, we looked at over 3,000 announced alliances from 1997 through 1999, and found that only 25 percent were equity-based. This percentage, however, rose to 62 percent when we looked at nearly 2,500 alliances formed between 2000 and 2002. A number of forces are driving equity-based alliance formations (see Exhibit 2).

Businesses have long blurred the boundaries between competition and cooperation. In the U.S. and Europe, cartels carved up important markets for much of the last century; in Asia, companies have long been bound together by cross-shareholdings. But in recent years, companies have begun to collaborate on an unprecedented scale.

Businesses have long blurred the boundaries between competition and cooperation. In the U.S. and Europe, cartels carved up important markets for much of the last century; in Asia, companies have long been bound together by cross-shareholdings. But in recent years, companies have begun to collaborate on an unprecedented scale.

In the recent past, alliances tended to be merely tactical – for instance, enabling a company to achieve its sales objective for individual export markets. But today’s strategic partnerships are often more far-reaching in their scope. For some industries, the urge to collaborate is particularly intense. For example, Europe’s heavy engineering and defense industries are banding together to cope with shrinking markets and to overcome national barriers to takeovers. The global auto industry – which wants to build a global web of distribution and product offerings and get around national restrictions – has entered into more than 400 deals in the past few years.

The same urge to collaborate is true for durable goods, business and financial services, entertainment and media, and pharmaceutical companies. Indeed, strategic partnerships are being formed in virtually every industry. The global equity alliance mix has also significantly changed. From 1994 to 1996, technology companies dominated the mix, representing nearly 50 percent of all equity alliance formations. Today a more even distribution prevails across all industries.

In 2000, Forbes and Thomson Financial noted that the number of publicly-announced alliances and acquisitions were nearly equal. Today, the number of alliances being formed worldwide continues to escalate by 25 to 35 percent annually. The current rate of formation is roughly 10,000 per year. Moreover, we found that the top 50 global alliance-forming firms averaging 150 publicly announced alliances, of which 59 percent are equity-based. We believe, as do many others, that the alliance will soon surpass the M&A as the predominant form of corporate integration.

Globalization, retrenchment and the pace of technological change

Companies today are constrained by their abilities to respond by the obvious limitations on their capital and managerial resources, especially given the loss of stockholder confidence and the contraction of capital markets. There is simply not enough money, time or personnel to be successful in all sectors and in all markets. Under these circumstances, it really should be no surprise that alliances, which are predicated on shared risk and shared resources, are regarded as a prudent tool for the use of scarce corporate resources, especially since they can increase shareholder value and help gain competitive advantages.

While the contraction of the capital markets is one stimulus toward for forming alliances, there are three primary reasons for the increasing growth of alliances:

1. The global meltdown of barriers to geographic expansion.

2. The retrenchment of major companies to their core competencies.

3. The rapid pace of technology innovation, development and adoption.

- Globalization: Revenues from offshore markets of the top 1000 U.S. and Asian/European firms have increased from 14 percent to 33 percent and 23 percent to 50 percent, respectively, between 1980 and 2000. It is not surprising that well over 50 percent of equity alliances formed over the past decade have multi-national partners.

- Core retrenchment: While companies were expanding globally, they were also retrenching at an unprecedented pace. Our surveys revealed that only 21 percent of the revenue of the top 1,000 Asian, U.S. and European firms was generated from their core businesses in 1980. In 2000, these same companies saw over 70 percent of their revenue coming from core business lines. Companies today that wish to explore opportunities outside their cores are increasingly utilizing equity alliances to achieve that goal.

- Pace of technology: As management was focusing on the core business, there was unprecedented technological innovation. Our research shows that 22 percent of the revenue of major global firms is generated by the introduction of new products each year; this is up from 15 percent in the 1980’s. It is no wonder that over 30 percent of all equity alliances contain some type of technology element. Alliances are a way for a firm to access innovative technology without an outright acquisition, avoid questionable expenditures before the technology is fully proven, and leapfrog the research and development cycle.

The diminishing reliance on acquisitions to invigorate growth

Many U.S. executives favor acquisitions as the best approach to creating growth and wealth. However, when we compare success rates between the “bond” and “buy” options, it is alliances that come out on top. Let’s examine some findings from a few recent studies:

- In a 1998 Barron‘s article entitled “Merger Mayhem,” Leslie Norton was quoted as saying “research studies indicate that between 60 percent and 80 percent of mergers (and acquisitions) are financial failures.”

- In a 2001 study of 118 mergers and acquisitions, KPMG found that 70 percent of them did not create shareholder value for the combined companies. KPMG also found no correlation between previous acquisition experience and success.

- A recent McKinsey & Co. study of 160 acquisitions, by 157 public companies across 11 industry sectors, found that 42 percent of acquirers had lower growth rates than their industry peers after the acquisition. Even more notable are the findings that 88 percent did not manage to accelerate their growth appreciably and that 60 percent of the companies failed to earn returns greater than the annual cost of capital required to do the acquisition.

- A BusinessWeek analysis of 302 major M&A’s revealed that 61 percent of the merged companies destroyed shareholder wealth. (BusinessWeek, October 14, 2002).

The dismal success rate for mergers and acquisitions should not be surprising, since acquisitions, while achieving full control, bring to the acquirer all parts of the acquired entity – both its strengths and weaknesses. Moreover, many acquisitions are processed in an auction environment, yielding what we call “the winner’s curse” – winning the bid with the highest price, and one that is often too high. Failure can also be defined as underperforming the stock market averages or not delivering on promised synergies, cost reductions, profit increases or accelerated development.

These failures can no longer go unnoticed or unreported. New accounting rules have eliminated pooling of interest and require the mandated write down of goodwill. A few examples include Sony’s purchase of Columbia Pictures, resulting in $2.7 billion writedown; Quaker Oats’ acquisition of Snapple ($1.4 billion); Dow Jones buying Telerate ($900 million): Eli Lilly purchasing PCS Health Systems ($2.4 billion), and the AOL Time Warner merger ($54 billion).

What drives senior executives to do M&A transactions? PWC has found that the top three reasons are: 1) access to new markets; 2) growth in market share; and 3) access to new products. However, the real question is not about the objectives themselves, but whether acquisitions are the best approach for achieving them?

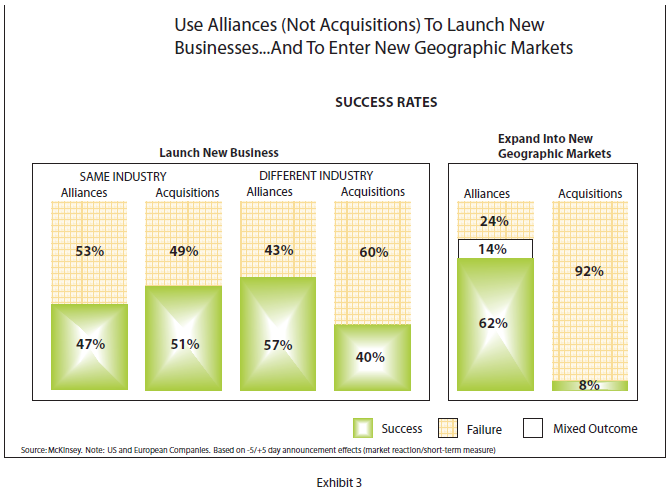

A recent McKinsey & Co. study takes issue with the acquisition tactic for two of the objectives. McKinsey found that alliances are more attractive than acquisitions when trying to launch a new business, or enter or expand into new geographical market (see Exhibit 3). Through cooperation, not acquisition, a company can break into new markets, obtain access to new technologies and gain economies of scale with, arguably, higher success and at lower cost than through acquisitions.

Alliances: Engines for growth and shareholder wealth

The facts favouring alliances over acquisitions are building and executives are taking notice. Consider the following:

- Harvard and Yale universities published results of a study of 1300 alliances that showed a positive share price movement in both partners’ shares on the day the alliance was announced. (B. Ananad & T. Khanna, “Do Firms Learn to Create Value? Case for Alliances,” Strategic Management Journal, 21, No. 3, 2000.)

- A 2000 study by Ernst & Young and The Wharton School revealed that alliances are one of the top five factors driving market value in all industries.

- Accenture has looked at the linkage between market capitalization and alliances. In 1999, alliances contributed over 12 percent of the total market cap for 40 percent of all companies. Accenture is forecasting that this will grow to 25 percent by 2004. (Accenture, The Point, Volume 2, issue 1, 2002).

- A recent study of the top 500 global companies by The Wharton School and the universities of Michigan and Bingham Young found that each partner’s stock price increased on the announcement of each new significant alliance.

- Alliances are yielding, on average, 50 percent higher ROIs for the top 1000 U.S. and non-U.S. global companies as compared to their core business.

In terms of alliance investment, we examined nearly 1,200 publicly announced equity alliances that were formed since 1995. We found that the median investment by a partner has increased from $28 million during the period 1988 to 1992 to $98 million today. We also found that the median investment for the top 25 percent of equity alliances was $1 billion for each partner.

Next, we looked at the level of buyouts of a partner’s interests for nearly 170 equity alliances formed since 1995. We found that the median buyout was $400 million. More importantly, buyout amounts are dramatically increasing. For example, the top 25 percent of equity buyouts of a partner’s interests have a median of $2 billion dollars.

When comparing acquisitions to alliances, acquisitions were unsuccessful in terms of increasing shareholder value in 67 percent of the transactions. In contrast, the alliance success rate is 80 percent for those firms that have developed alliance skills as a core competency.

While we are advocates for alliances, we are not opposed to acquisitions. Quite the contrary, in fact, alliances often lead to a merger or acquisition. The understandable premise is that it is sometimes better to live together a while before tying the knot.

The art of the deal: Best practices

Compared to acquisitions, alliances are much more complex and time consuming to negotiate and close (see Exhibit 4). In mergers and acquisitions, the principal concerns are price, structure, representations and warranties, and indemnification. These concerns are also issues in alliances, but there are additional ones as well.

They are:

- Scope and limitations on the scope of the alliance

- Capitalization and relative ownership resulting from that initial capitalization

- Governance, which is actually two issues: Policy control and operational control, and the subcategory of disputes and dispute resolution mechanisms

- Allocation of risks and returns, including allocation of liabilities in the event that the alliance fails

- Technology issues (The form of initial IP transfers, rights to new technologies and policies such as the rights or restrictions on the new entity or partner to sublicense technology)

- Restrictions on transfers of ownership

- Exit strategies and their triggering events

If agreement on these issues is to be reached, the parties must covey their willingness to find mutually agreeable solutions through a win-win approach to the negotiations. It is important for all involved to bear in mind that the objective is to form a partnership, not to take control. Winning every point will only leave the weaker partner without the incentive to be a good partner.

Let’s also share with you results from surveys of 500 CEOs whose companies had engaged in alliances successfully. Below we highlight what they viewed as key reasons why some of their alliances have failed:

- Selecting the first partner identified; in other words, not identifying the market of possible partners up front.

- Parties had not engaged early enough in frank dialogue on the objectives, tactics and constraints.

- Parties had not included the ultimate managers of alliance in the due diligence process or in the decision to proceed.

- Parties had generally failed to establish effective and collaborative communications among the rank and file.

- Parties had created “too loose of an agreement.” Exhibit 5 illustrates the appropriate steps in the alliance formation process. Many executives underestimate the magnitude of time and effort required to forge a sustainable alliances. Unless alliance skills are a core competency, the typical company will find it a daunting challenge to bridge the gap between strategy and implementation.

A key element in making the process a success is bilateral due diligence, which we identify as the co-planning box depicted on the exhibit above. This is not legal and accounting due diligence; it is due diligence performed by marketing, planning, manufacturing, systems, engineering and other line personnel, including the alliance managers from both sides. Their deliverable is a Joint Tactical and Strategic Plan – the business plan for the alliance. It justifies the alliance, or correctly terminates it before it starts: it sets the performance measures and milestones, and it estimates the time and resources required.

Governance

As we have noted, each alliance is comprised of numerous building blocks. Each is unique in terms of the content of the blocks and their relative importance, with one exception. It is indisputable that governance is the capstone, if not the foundation, of any alliance structure. Yet governance is the most frequently mishandled and inadequately addressed element in alliance building. Alliance governance presents the greatest challenge because of the many rights, privileges and obligations that must be addressed to form a functional, sustainable structure.

Under the traditional corporate model, the duties and responsibilities of directors are straightforward and well defined by statute and case law. Directors have strict fiduciary duties to shareholders and the corporation; they perform executive oversight and they monitor performance.

In the context of alliances, the duties of directors are quite a bit muddier and broader. First, depending on the legal form of the entity chosen for the alliance, fiduciary duties can be modified and minimized, if not eliminated altogether. Directors more directly represent the interests of distinct stakeholders. Disputes are, therefore, more likely; and so, dispute resolution mechanisms are necessarily more complex, sometimes draconian. Dispute resolution mechanisms are means to break deadlocks and include such measures as shifting responsibility to executives at the parent companies, special directors, mediation, and arbitration.

Second, the life of a corporation is supposedly infinite; an alliance generally has finite objectives and lives. So exit strategies are in partners’ thoughts from the earliest stage of negotiation. Therefore, the events that can trigger exits need to be clearly defined up front. Other issues include, but are not limited to, the on-going capital needs of the enterprise, related-party transactions, and the rights to new technologies invented within the partnership. All these rise to become board-level issues in the context of an alliance.

A small sample of the governance issues that will need to be addressed are:

- What legal form the alliance should take (C corporation, general partnership, limited partnership, LLCs)

- Whether operational control will be delegated differently than organizational control.

- Whether interest may be transferred to other parties and if so under what procedures and circumstances

- How profits (or losses are to be allocated

- What each party’s responsibility may be for future capital requirements

- When and how the alliance may be terminated and what each partner receives

- What liabilities shall be assumed by each partner upon termination

- What exits mechanisms are most appropriate

Many executives instinctively equate equal contribution with equal governance. Consider Fuji Xerox, which is based in Tokyo, and which is a nearly a $9 billion (U.S.) 50:50 solution joint venture between Xerox and Fuji Photo Film Co. Ltd. The board of directors has 15 members, of which four are American and the rest Japanese. The breakdown by company is: Fiji Xerox (five), Fiji Photo (two), Independent directors (four). Yotaro Kobayashi is also a member of the board of directors of Xerox Corporation, as is the vice chairman of Fiji Xerox.

This alliance has been very successful for both companies. In fact in 2001, the Fuji Xerox alliance became a critical source of funds for Xerox as equity and capital markets contracted for the company. Xerox has since sold half of its interest in Fuji Xerox for $1.3 billion to Fuji Photo.

Never before has management been challenged by so many opportunities and threats. Management is asked to act faster, invigorate growth and capture even greater profits, while using fewer resources and capital in the process. Under these circumstances, it should surprise no one that alliances, which are predicated on shared risk, and the prudent use of capital and resources, are becoming an increasingly important approach for increasing shareholder wealth and competitive strength. The question for major companies is no longer whether forging equity alliances is a responsible corporate tactic.

Instead, corporate executives must address other questions such as:

- What type of equity alliance is most appropriate to invigorate growth and gain competitive advantages?

- How do we, under a particular set of facts and circumstances find the “best” partner?

- How do we manage the alliance process and negotiate a “win-win” arrangement?

- Have we engaged the best advisors – strategic, legal and transaction?

Exploring and resolving these issues will enable each party in an alliance to meet its expectations for forming or joining the alliance in the first place.