A CRISIS IN LEADERSHIP

Over the past several years, the swift, and most often forced, depart u res of CEOs have become commonplace at companies in North America, Europe and Japan. Among those affected are Xerox, Lucent, JC Penney, Gillette, Texaco and Nissan. Nor does the list end here.

Today, a new psychology grips the board of directors at companies like those mentioned above: If your CEO has failed, you should recruit from outside the company, where the pastures are always greener.

But those boards would be wise not to adopt that new psychology. For example, Rick Thoman at Xerox came from outside the company. Today, Xerox is fighting for its life and some think it will not be able to survive. The crucial lesson is this: While recruiting from the outside and taking risks may seem like a solution, it is one for the short term. For the long term, management must build, develop and maintain a pipeline of skilled, prepared leaders from within the company.

Many companies have practised this lesson. Xerox was one, but it failed. It did so because it failed to develop managers who:

- Were prepared and had the necessary skills to be effective at the next level

- Could understand what is unique about their job, especially compared to the jobs held by their boss and direct reports

- Could hold their direct reports and themselves accountable for achieving the right results in the right way.

An important truth underlies these three important points: A crisis in leadership is the result of a company-wide breakdown rather than the actions or failure of one person. Moreover, finding the perfect CEO does not solve the crisis. Nor does going outside to fill senior leadership positions. In fact, going outside is an admission of failure and not very likely to succeed. Hiring an outsider masks the hard truth that a company has not developed a pipeline of leaders from among its ranks who can step in and manage the bigger challenges of the day.

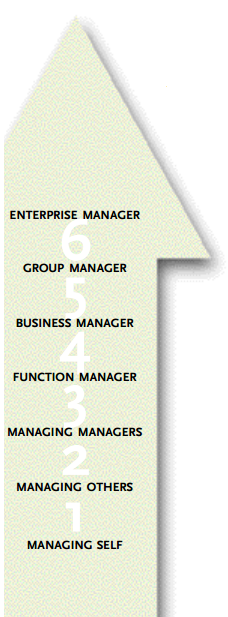

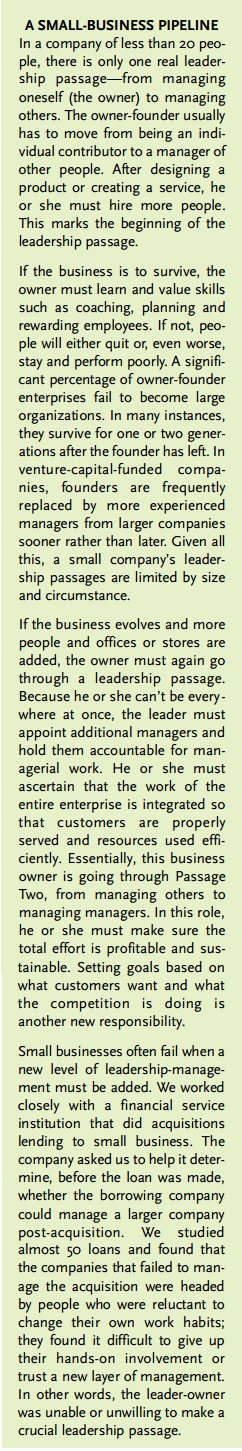

Based on work originally done at General Electric in the 1970s (referred to as Critical Career Crossroads and developed by Walter Mahler), and later expanded to and tested in more than 80 companies, we developed a six-passage model for understanding the leadership requirements throughout an entire company. We call this model The Leadership Pipeline (The Leadership Pipeline, by Ram Charan, Stephen J. Drotter and Jim Noel, Jossey-Bass Inc., 2001).

The six turns, or passages, in our pipeline are major events in the life of a leader. Grasping what each passage entails, and the challenges involved in making each transition, will help organizations build a leadership pipeline. It will also help build a leadership culture that will enable the organization to respond to changes and threats in the business environment.

THE LEADERSHIP PIPELINE

PASSAGE 1: managing self to managing others

New, young employees usually spend their first few years in an organization as individual contributors. Whether in sales, accounting, engineering or marketing, their skill requirements are primarily technical or professional. They contribute by doing the assigned work within given time frames and in ways that meet objectives. By sharpening and broadening their individual skills, they make increased contributions and are then considered for promotions.

From a time-application standpoint, learning involves planning (so that work is completed on time), punctuality, content, quality and reliability. The work values to be developed include accepting the company’s culture and adopting professional standards. When people become skilled individual contributors who produce good results, especially when they demonstrate an ability to collaborate, they usually receive additional responsibilities. When they demonstrate an ability to handle these responsibilities and adhere to the company’s values, they are often promoted to first-line manager.

When this happens, these individuals are at Passage One. Though this might seem like an easy, natural leadership passage, it’s often one where people trip. The highest-performing people, especially, are reluctant to change; they want to keep doing the activities that made them successful. As a result, many people make the transition from individual contributor to manager without actually making a behavioral or value-based transition. In effect, they become managers without realizing or accepting the requirements. Many consultants, for instance, have skipped this turn, having moved from transitory team leadership to business leader without absorbing much of the learning in between. When business leaders miss this passage, the result is frequently disaster.

First-time managers need to learn how to reallocate their time so that they not only complete their assigned work but also help others perform effectively. They must shift from doing work to getting work done through others. This is especially difficult for first-time managers. Part of the problem is that they still prefer to spend time on their old work, even as they take charge of a group. Yet the pressure to spend less time on individual work and more time on managing will increase at each passage. If people don’t start making changes in how they allocate their time from the beginning, they’re bound to become liabilities as they move up. It’s a major reason why pipelines clog and leaders fail.

The most difficult change for managers to make at Passage One involves values. Specifically, they need to learn to value managerial work rather than just tolerate it. They must believe that making time for others—planning, coaching, and the like—is a necessary task and their responsibility. More than that, they must view this other-directed work as mission-critical to their success. For instance, first-line knowledge managers in the financial services industry find this transition extremely difficult. They value being producers, but they must learn to value making others productive. Given that these values had nothing to do with their success as individual contributors, it’s difficult for them to make this dramatic shift.

While changes in skills and time application can be seen and measured, changes in values are more difficult to assess. Someone may appear to be making the changes demanded by this leadership turn. But, in fact, he or she is actually adhering to individual-contributor values. Value changes will take place only if upper management reinforces the need to shift beliefs, and if people find that they’re successful at their new jobs after a value shift.

PASSAGE 2: managing others to managing managers

Few companies address this passage in their training, even though this is the level where a management foundation is constructed, and even though level-two managers select and develop the people who will eventually become a company’s leaders.

Perhaps the biggest difference from the previous passage is that, at this level, managers must only manage. They need to divest themselves of individual tasks. The key skills they must master during this transition include selecting people to turn Passage One, assigning managerial and leadership work to them, measuring their progress as managers, and coaching them. At this point, managers must also see beyond their own job description and consider the bro a d strategic issues that affect the business overall.

Too often, people who have been promoted to manager-of-manager positions have skipped Passage One; they were promoted to first-line managers but didn’t change skills, time application or work values. As a result, they clog the leadership pipeline because they hold first-line managers accountable for technical work rather than managerial work. They help maintain and even instill the wrong values in those individuals who report to them. They are essentially unable to differentiate between those who can do and those who can lead.

Managers at Passage Two need to be able to identify value-based resistance to managerial work, a common reaction among first-line managers. They need to recognize that the software designer who would rather design software than manage others cannot be allowed to move up to a leadership role. No matter how brilliant he or she might be at designing software, the individual will block the leadership pipeline if he or she does not derive satisfaction from managing and leading people. In fact, one of the tough responsibilities for managers of managers is to return people to individual contributor roles if they don’t shift their behaviour and values.

Coaching is also essential at this level because first-line managers frequently don’t receive formal training in how to be a manager; they’re dependent on their bosses to instruct them on the job. Coaching requires managers to go through the instruction-performance-feedback cycle with their people; some managers aren’t willing to reallocate their time in this way. In many organizations, coaching ability isn’t rewarded (and the lack of it isn’t penalized). It’s no wonder that relatively few managers view coaching as mission-critical.

PASSAGE 3: managing managers to managing a function

Making this transition is tougher than it appears. While the difference between managing managers and managing a function might appear to be negligible, a number of significant challenges lurk below the surface. For example, communicating with the individual-contributor level now requires penetrating at least two layers of management, thus making the development of new communication skills mandatory. Functional heads must also manage some areas that are unfamiliar to them. They must not only endeavour to understand this foreign work but learn to value it as well.

At the same time, functional managers report to multifunctional general managers. They therefore have to become skilled in considering other functional needs and concerns. Team-play with other functional managers and competition for resources based on business needs are two major skills they must learn. At the same time, managers at this level should learn how to blend the strategy for their own unit with the business’s overall strategy. This means participating in business-team meetings and working with other functional managers, and spending less time on purely functional responsibilities. This is why it is essential that functional managers delegate responsibility for overseeing many functional tasks.

Succeeding in this leadership passage also requires increased managerial maturity. In one sense, maturity means thinking and acting like a functional leader rather than a functional member. But it also means that managers need to adopt a broad, long-term perspective. Long-term strategy, especially applied to their own function, is usually what gives most managers trouble at this stage. At this level, effective leadership entails creating a functional strategy that enables them to do something better than the competition. Whether it’s coming up with a method to design more innovative products or reach new customer groups, these managers must push the functional envelope. They must also push it into the future for a sustainable competitive advantage rather than just for an immediate, but temporary, edge.

PASSAGE 4: functional manager to business manager

This leadership passage is often the most satisfying and challenging of a manager’s career. For any organization, it’s mission-critical: Business managers are responsible for the bottom line.

Business managers usually have significant autonomy, which people with leadership instincts find liberating. They also are able to see a clear link between their efforts and bottom-line results. At the same time, this passage also re presents a sharp turn: A major shift in skills, time application and work values must take place. This is not simply a matter of thinking more strategically. Rather than consider the feasibility of an activity, a business manager must examine it from a short- and long-term profit perspective.

There are probably more new and unfamiliar responsibilities here than at other levels. For people who have only been in one function their entire careers, the position of business manager represents unexplored territory; they are suddenly responsible for many unfamiliar functions and outcomes. Not only do they have to learn to manage different functions, but they also need to become skilled at working with a wider variety of people than ever before; they need to become more sensitive to functional diversity issues and able to communicate clearly and effectively.

Even more difficult is the balancing act between future goals and present needs, and making trade-offs between the two. Business managers must meet quarterly profit, market share, product and people targets and, at the same time, plan three- to five-year goals. The trial of balancing short- and long-term thinking is one that bedevils many managers at this turn. It is why allocating time to think is a major requirement at this level: Managers need to stop doing something every second of the day and reserve time to reflect and analyze.

PASSAGE 5: business manager to group manager

This is another leadership passage that, at first glance, doesn’t seem arduous. The assumption is that if you can run one business successfully, you can do the same with two or more businesses. The flaw in this reasoning begins with what is valued at each leadership level. A business manager values the success of his own business; a group manager values the success of other people’s businesses. The distinction is critical because some people derive satisfaction only when they’re the ones receiving the lion’s share of the credit.

As you might imagine, a group manager who doesn’t value the success of others will fail to inspire and support the business managers who report to him. Or, his or her actions might be governed by frustration; the individual is convinced he or she could operate the various businesses better than his or her manager. In either instance, the leadership pipeline becomes clogged with business managers who aren’t operating at peak capacity because they’re not being properly supported or their authority is being usurped.

group managers must master four skills:

1. Evaluate strategy in order to allocate and deploy capital. This is a sophisticated skill that involves learning to ask the right questions, analyzing the right data, and applying the right corporate perspective to understand which business strategy (prepared by business managers) has the greatest probability of success, and should there f o re be funded.

2. Develop business managers. Group managers need to know which function-managers are ready to become business managers. Coaching new business managers is also important.

3. Develop and implement a portfolio strategy. This is quite diff e rent from a business strategy and demands a shift in how he or she perceives the business. This is the first time managers have to ask these questions: Do I have the right collection of businesses? What businesses should be added, subtracted or changed to position us properly and assure current and future earnings?

4. Assess whether they have the right core capabilities to win. This means avoiding wishful thinking, looking at resources objectively, and making a judgment based on analysis and experience.

A leader at this level must have a global perspective. People may master the required skills, but they won’t perform at full leadership capacity if they don’t think in broad terms, aren’t able to factor in the complexities of running multiple businesses, and don’t think in terms of community, industry, governmental and ceremonial activities. They must also prepare themselves for the bigger decisions, greater risks and uncertainties, and the longer time spans inherent to this leadership level. They must always be aware of what Wall Street wants.

PASSAGE 6: group manager to enterprise manager

When the leadership pipeline becomes clogged at the top, all leadership levels suffer. CEOs who have skipped one or more passages can diminish the performance of direct reports and individuals all the way down the line. They fail to develop other managers effectively, and don’t fulfill the responsibilities that come with this position.

The transition during the sixth passage is much more focused on values than skills. To an even greater extent than at the previous level, people must reinvent themselves as enterprise managers. They must set direction and develop operating mechanisms to know and drive quarter-by-quarter performance that is in tune with longer-term strategy.

They must thoroughly understand how the organization executes and gets things done. The trade-offs involved can be mind-bending, and enterprise leaders learn to value these trade-offs. In addition, this new leadership role requires an ability to manage a long list of external constituencies proactively.

Enterprise leaders need to come to terms with the fact that their performance as a CEO will be based on three or four high-impact decisions each year. There’s a subtle but fundamental shift in responsibility from strategic to visionary thinking, and from an operating to a global perspective. There’s also a letting-go process that should take place during this passage, if it hasn’t taken place already. Enterprise leaders must let go of the pieces, i.e., the individual products and customers, and focus on the whole, i.e., how well do we conceive, develop, produce and market all products to all customers.

Finally, at this level, a CEO must assemble a team of high-achieving, ambitious direct reports, knowing that some of them want his job, yet picking them for the team despite this knowledge. Also, this is the only leadership position that must shape the soft side of the enterprise.

leadership pipeline problems occur at this level for two reasons:

1. CEOs are often unaware that this passage requires a significant change in values. Too many CEOs fail because they didn’t recognize the requirement to make a full t urn. They maintain the same skills, time applications and work values that served them well as group managers, and never adjust their self-concept to fit their new leadership role. They behave as though they are running a portfolio of businesses, not one entity. They must have the will and determination to change their work values.

2. It is difficult to develop a CEO for this particular leadership transition. Preparation for the position is the result of a series of diverse experiences over a long period of time. The best approach provides carefully selected job assignments that stretch people over time and allow them to learn and practise the necessary skills. Though coaching might be helpful, people usually need time, experience and the right assignments to develop into effective CEOs.

THE BENEFITS OF A PIPELINE

Too often, organizations don’t realize that their leaders aren’t performing at full capacity because they aren’t holding them accountable for the right things. Companies focus only on the economic requirements of a given job rather than the skills, time application and work values of a specific leadership level. As a result, a business manager is allowed to spend most of his or her time acquiring new customers rather than developing an effective business strategy. Or the business manager’s boss, the group manager, never questions or explores what the business manager values about his or her work, and whether those values are appropriate for the leadership the company requires. But when this business manager’s strategy is flawed and important goals aren’t achieved, the group manager isn’t held accountable (or held accountable for the right thing).

A well-defined leadership pipeline delivers important benefits

1. By establishing appropriate requirements for the six leadership levels, companies can greatly facilitate succession planning, and leadership development and selection processes in their organizations.

2. Individual managers can clearly see the gap between their current performance and the desired performance. They can also see gaps in their training and experience, and where they may have skipped a passage (or parts of a passage) and how that’s hurting their performance.

3. HR can make development decisions based on where people fall short in skills, time application and work values, rather than rely on generalized training and development programs.

4. An individual’s readiness for a move to the next leadership level can be evaluated objectively rather than tied to how well they performed in their previous position.

5. Leadership passages provide companies with a way to improve selection. Rather than basing their selection decisions on past performance alone, personal connections or preferences, managers can be held to a higher, more effective standard. Organizations can select someone to make a leadership turn when an individual is demonstrating some of the skills required at the next level.

6. A defined pipeline provides organizations with a diagnostic tool that helps them identify mismatches between individuals’ capabilities and their leadership level. Therefore, remedying the situation or, if necessary, removing the mismatched person, which is more likely.

7. It helps organizations move people through leadership passages at the right speed. People who ticket-punch their way through jobs don’t absorb the necessary work values and skills. The pipeline provides a system for identifying when someone is ready to move to the next leadership level.

8. It reduces the time needed to prepare an individual for the top leadership position in a large corporation. Because the pipeline clearly defines what is needed to move from one level to the next, there’s little or no wasted time on jobs that merely duplicate skills.

From a pure talent perspective, however, the most significant benefit of a pipeline is that you don’t need to bring in stars to prime the leadership pump and unclog the pipeline. You can create your own stars up and down the line, beginning at the first level when people make the transition from managing themselves to managing others. By moving people upward only when they have mastered the assigned level greatly increases their chances of success. Clearly defining the new requirements enables them to help themselves and help their direct reports. Everyone wins and so does the company. Recruiting outside for top positions will be greatly reduced.