In the global economy, investing in technology – and only technology – is unlikely to pay off. As this author writes wealth will flow to those that exhibit innovation in a dominant paradigm, own a strong intellectual property position in critical technologies, and have high-performance business models (Wal-Mart). Below, he describes how managers can achieve these ends.1

It’s sometimes said that there’s nothing more practical than a good theory. Whether they realize it or not, managers need a theoretical understanding of enterprise growth and development. In this article, we propose the adoption of a conceptual framework that will help executives lead their organizations in highly competitive global markets. For some, it will change frames of reference and accepted priorities in terms of what’s important to build, own, and manage.

To be useful, a theoretical framework must be general enough to provide guidance in a variety of situations. This calls for judiciousness so that an overwhelming number of variables don’t render analysis an impossible task. It also calls for sufficient generality and flexibility, so that the concepts can be applicable in a wide variety of circumstances. However, the theory must not be so general and academic that it has little to do with practical management problems.

Management theory is young and fragmented, and generally not much of a guide for executives, except on certain, narrow issues. The framework presented here can be helpful with the big-picture issues.

This essay presents the Dynamic Capabilities Framework (Teece et al., 1990, 1997; Teece, 2007), which is increasingly providing the intellectual infrastructure for both theoretical and applied analyses of strategic management and other issues facing business decision makers. While originated by the author of this paper, a broad panoply of scholars and executives is now contributing to its further development.2

The growing importance of intangible assets

The Dynamic Capabilities Framework is animated by the recognition of several global megatrends that impact the contemporary business enterprise operating in hypercompetitive environments. Perhaps the most critical of these trends is that access to global transportation and information flows is so widespread that some say the world is “flat” (Friedman, 2007). In particular, intermediate goods and services that might once have been hard to access are now widely available, a reality which has created a system of global specialization. But on this “flat” landscape, characterized by hyper-competition, the capabilities required to orchestrate and deploy the available resources remain scarce and geographically isolated.

As a result of the greater ability to outsource almost anything and everything, the traditional competitive sources of differentiation based on economies of scale and scope have been eroded. If your market is too small to capture scale economies for an input or even a whole product, then you should source from companies that have achieved them already. Textbooks need to be rewritten to recognize the new reality.

Fortunately, there are other bases of competitive advantage unrelated to scale. The prime example is the generation, ownership, and management of intangible assets, which have risen to overshadow economies of scale in importance for enabling the enterprise to build and sustain a successful position.

Perhaps the most important class of intangible assets not universally available is technological know-how. Know-how and other intangibles are increasingly the “bottleneck assets” that allow innovating firms to differentiate and establish some degree of competitive advantage. They cause “hills”—and sometimes high “mountains”—to appear on otherwise flat competitive landscapes. Value can flow to the enterprise from the astute creation, combination, transfer, accumulation, and protection of intangible assets. Such assets are the new “natural resources” of the global economy. But they are not naturally occurring and depend on managerial action and, in part, on national systems of innovation (Nelson, 1993).

Intangible assets in general are a very economically interesting asset class, with powerful implications for building and maintaining competitive advantage at the enterprise level. Intangible assets are hard to “build” and difficult to manage. They are also unlikely to be traded (i.e., markets, if they exist, will be “thin”) because their underlying value often derives from the presence of complementary assets, which limits the number of buyers who will be willing and able to pay the knowledge asset’s full potential strategic value. Furthermore, knowledge assets are generally costly to transfer and can even be difficult to specify fully in a contract (Teece, 1981). As a result, these assets are harder to access than many other asset classes.

Ironically, even in natural resource industries, profits (for the business enterprise, but not necessarily for the nation-state) flow fundamentally from the ownership and use of intangibles, and only less so from ownership of the resource. The highest profits flow to those who develop extraction technologies, deploy them effectively and safely, and build privileged relationships with nation states and other constituencies. Accordingly, in the petroleum industry, oil in a fundamental sense is “found” in the mind, not in the ground; locating new reserves in deep water requires both (organizationally embedded) know-how and, in many jurisdictions, relationships with nation-states to secure exploitation and production rights. Table 1 summarizes the differences between intangible and physical assets along selected dimensions.

Table 1: Intangible Assets Compared With Physical Assets

| Intangible Assets | Physical Assets | |

| Variety | Heterogeneous | Homogeneous |

| Property rights | Often fuzzy | Usually clear |

| Market transactions | Infrequent | Frequent |

| General awareness of transaction opportunity | Low | High |

| Recognized on balance sheets | No | Yes |

| Possible strategic value | High | Low |

Another intangible asset of central importance (besides knowhow) is a firm’s business model for a given market, i.e., the structure of a firm’s value proposition for its customers (Chesbrough and Rosenbloom, 2002; Teece, 2010a) and the design of the business that will deliver a solution to the customer. Business-model innovations are critical to success in unsettled markets where traditional revenue and pricing models are no longer applicable. The Internet allows and requires business model innovation.

In particular, the Internet requires new pricing structures because users are accustomed to getting information for free. Information providers are challenged to think of ways of charging for ancillary or premium services (so-called “fremium” approaches) while not running afoul of Internet users’ expectations of receiving free information.

The other main classes of intangible assets are technological know-how, business process know-how, customer and business relationships, reputations, organizational culture and values, as well as formally identified intellectual property. The ability to prevent (or punish) the imitation of the key intangibles is necessary in order for the firm to capture value from its assets. Legal barriers to imitation protect some knowledge assets, although these are of limited importance in some industries due either to the pace of change or weak rights enforcement (e.g. digital music).

Because knowledge assets by themselves will not yield value, they must almost always be combined with other intangible and physical complements and bundled as a product to yield value for a customer. Ownership and/or control of complementary assets are therefore also necessary for competitive success (Teece, 1986). Textbooks are only now starting to recognize the fundamental shifts that have taken place in the basis of competitive advantage. The implications for business strategy, organization, and management education are monumental.

The growing importance of complements both inside and outside of the firm is a case in point. The vital role of complementors changes the nature of the required technology management approaches and business strategies because innovation in one product or service often increases the value of their complement(s). For example, improvements in software help drive demand for computing hardware, and vice-versa. Likewise, the development of high-octane fuels in the 1940s by oil refiners enabled the creation of high-compression engines by auto manufacturers.

It is also the case that intangible assets are rarely recorded on corporate balance sheets. As a consequence, existing accounting-based frameworks have a hard time coming to grips with them. Alan Greenspan, former chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank, once noted the challenge of “developing a framework capable of analyzing the growth of an economy increasingly dominated by conceptual products” (Greenspan, 2004). Conceptual products are steeped in intangible assets.

These changes in the economy clearly call for a new theoretical framework for understanding and guiding the growth of firms increasingly involved in creating and marketing conceptual, rather than physical, products. The Dynamic Capabilities Framework recognizes these considerations.

From knowledge assets to dynamic capabilities

As new bases of competitive advantage have gained in significance, old ways of looking at competition have been supplanted. Porter’s Five Forces framework (Porter, 1980), which applied the structure-performance paradigm of industrial organization economics to strategy, focused on evaluating suppliers, customers, and the threat of new entrants and/or substitute products. This framework is not without insight, but it’s not up to the task of revealing the dominant logic of value capture in most new industries, as well as many of the old.

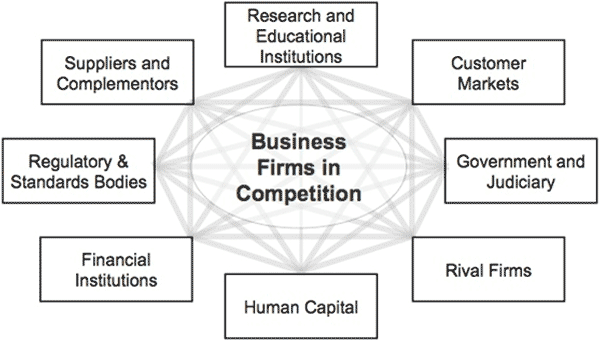

Hence, firms need to take a more comprehensive view of the environment in which they must compete. Such a view needs to include not only buyers and suppliers but the local market for skilled workers (since they are not entirely mobile internationally), universities (for access to both highly educated talent and faculty research), financial institutions (especially venture capital), the legal system (especially intellectual property law and employment law), and the domestic political situation. Figure 1 displays these factors and their interaction.

Figure 1: The Business Ecosystem

In order to embrace these new elements of competition, the Dynamic Capabilities Framework has emerged. It offers a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to managerial decision-making. No other framework offers, or purports to offer, a comprehensive and multidisciplinary, research-based perspective on key strategic challenges. The Dynamic Capabilities Framework helps identify the factors likely to impact enterprise performance. It is gradually developing into a (interdisciplinary) theory of the modern corporation (Teece, 2010).

The Dynamic Capabilities perspective goes beyond a financial-statement view of assets to emphasize the “soft assets” that management needs to orchestrate resources both inside and outside the firm. This includes the external linkages that have gained in importance, as the expansion of trade has led to greater specialization. It recognizes that to make the global system of vertical specialization and co-specialization work, there is an enhanced need for the business enterprise to develop and maintain asset alignment capabilities that enable collaborating firms to develop and deliver a joint “solution” to business problems that customers will value.

Dynamic capabilities can usefully be thought of as belonging to three clusters of activities and adjustments: (1) identification and assessment of an opportunity (sensing); (2) mobilization of resources to address an opportunity and to capture value from doing so (seizing); and (3) continued renewal (transforming). These activities are required if the firm is to sustain itself as markets and technologies change, although some firms will be stronger than others in performing some or all of these tasks. Performance of these activities draws on all the skills and disciplines used in the curriculum of business schools everywhere. The Dynamic Capabilities Framework helps organize and harness (academic) disciplinary knowledge so as to apply it to the task of building durable competitive advantage at the enterprise level.

Sensing is an inherently entrepreneurial set of capabilities that involves exploring technological opportunities, probing markets, and listening to customers, along with scanning the other elements of the business ecosystem. It requires management to build and “test” hypothesis about market and technological evolution, including the recognition of “latent” demand. The world wasn’t clamoring for a coffeehouse on every corner, but Starbucks, under the guidance of Howard Schultz, recognized and successfully exploited the potential market. As this example implies, Sensing requires managerial insight and vision – or an analytical process that can be a proxy for it.

Seizing capabilities include designing business models to satisfy customers and capture value. They also include securing access to capital and the necessary human resources. Employee motivation is vital. Good incentive design is a necessary but not sufficient condition for superior performance in this area. Strong relationships must also be forged externally with suppliers, complementors, and customers.

Companies that successfully build and orchestrate assets within the ecosystem stand to profit handsomely. Apple retained an estimated 40 percent of the gross profits from the entirety of the value chain on its hard drive-based iPods, despite manufacturing no part of the product itself (Linden et al., 2009). This is not counting the revenue from licensing makers of iPod accessories or sales from the iTunes Music Store.

Transforming capabilities are needed most obviously when radical new opportunities are to be addressed. But they are also needed periodically to soften the rigidities that develop over time from asset accumulation, standard operating procedures, and insider misappropriation of rent streams. A firm’s assets must also be kept in alignment to achieve the best strategic “fit”: firm with ecosystem, structure with strategy, and assets with each other. Complementarities need to be constantly managed (reconfigured as necessary) to achieve evolutionary fitness, avoiding loss of value should market leverage shift to favor external complements.

Apple has proved to be a paradigmatic practitioner of dynamic capabilities as it has created and transformed a series of markets. Table 2 shows how each of its major product introductions reflected aspects of the major categories of dynamic capabilities. In particular, Apple’s strategy implementation has created and shaped markets.

Table 2: Dynamic Capabilities at Apple

| Sensing | Seizing | Transforming | Result | |

| iPod | existing mp3 players were too “geeky” | create an aesthetically appealing portable device with a simple interface over an accelerated product development cycle; later: improve appropriability with exclusive FairPlay DRM in the iTunes Music Store | port iTunes software to rival Windows platform; expand into content distribution with the iTunes Music Store; shift company emphasis from computers to consumer electronics | domination of the portable digital music player market; expansion to video capabilities (playback and distribution). |

| iPhone | existing “smart phones” retained an awkward interface too close to their cell phone roots. | create a multimedia phone with a large screen and an intuitive interface; promote complementary asset creation with the App Store infrastructure. | develop telephony capabilities; enter the regulated telephony market | one of the only companies making money with smart phones |

| iPad | “netbooks” provide an unsatisfying computing experience and “E-readers” provide limited functionality. | scale up the iPhone interface to provide a richer multimedia platform without phone functionality. | extend the “simple interface” aesthetic to a computing platform. | (too early to know) |

In addition to Apple’s ability to identify and orchestrate new asset combinations, wealth in the global economy flows to innovation within a dominant paradigm (Intel), a strong intellectual property position in critical technologies (Qualcomm), and high-performance business models (Wal-Mart). The important lesson is that investing in technology by itself is unlikely to pay off. Entrepreneurial managers and leaders building and deploying intangible assets are critical success factors. Capturing value is never certain, but it can be managed.

References

Baranskaya, Anna, and Teece, David J. (forthcoming). “Business Model Dashboards and Design Algorithms: Lessons from Apple’s iPod, iPhone, and iPad.”

Friedman, Thomas L. (2007). The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Linden, Greg, Kraemer, Kenneth L., and Dedrick, Jason (2009). “Who Captures Value in a Global Innovation System? The case of Apple’s iPod.” Communications of the ACM. 52(3): 140-144.

Nelson, Richard R. (ed.) (1993). National Systems of Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. New York: Free Press.

Teece, David J. (2007). “Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Microfoundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance,” Strategic Management Journal, 28(13): 1319-1350.

Teece, David J. (2010). “Technological Innovation and the Theory of the Firm: The Role of Enterprise-level Knowledge, Complementarities, and (Dynamic) Capabilities.” In N. Rosenberg and B. Hall (eds.) Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, Volume 1. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Teece, David J., Pisano, Gary, and Shuen, Amy (1990) Firm Capabilities, Resources, and the Concept of Strategy. Center for Research in Management. University of California, Berkeley, CCC Working Paper 90-8.

_______________________________ (1997) Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7): 509-533.

- This paper draws in part on Teece (2007) and on Baranskaya and Teece (forthcoming).

- Dynamic Capabilities is now a well-established framework for guiding research and practice in the field of strategic management. Teece et al (1997) is the single most cited paper in business and economics from 1995 to 2005 according to Thomson’s ScienceWatch. Since 2006, articles concerning dynamic capabilities have been published in business and management journals at a rate of more than 100 per year (Di Stefano et al., 2010). And an increasing number of these articles contain new empirical research. This work is now beginning to trickle through to management practices.