While working out of Italy for the last dozen years, Canadian newspaper columnist Eric Reguly has typically avoided some of the world’s most exquisite tourist sites. He doesn’t have an aversion to history. He just considers crowds wearisome, an assault on the “artistry and elegance” of previous generations. But during the early days of the COVID-19 crisis, he reported having a delightful experience strolling the Piazza Navona, where he could hear the square’s baroque fountains for the first time.

“Normally,” Reguly wrote in The Globe and Mail in early March, “the long oval expanse, which traces the shape of the ancient Stadium of Domitian and is now dominated by a Gian Lorenzo Bernini masterpiece, the Fountain of the Four Rivers, is a mass of babbling humanity, stuffed with jugglers, musicians, cheesy artists, several thousand tourists with selfie sticks and café patrons paying extortionate prices for cappuccino and gelato.”

Despite enjoying his walk, Reguly was out and about because he was covering the impact of the coronavirus outbreak on tourism. And yet, he wasn’t alone. At Tucci, a café with 100 tables, he came across two patrons from Scotland who saw the emerging global crisis as an opportunity to get a better return on an Italian vacation. “We’re taking a calculated risk,” noted Alison Essom, an insurance company worker from Edinburgh.

Business leaders can learn a lot from Essom and her travel partner. After all, the emerging pandemic quickly shut down Italy along with the rest of the world, so anyone seeking a good vacation amid the chaos and rising death count was misguided.

In other words, when health officials are issuing social-distancing warnings, nobody should be taking unnecessary risks and hoping to benefit from the situation.

What should businesses be doing? That’s a tough question, since we’re navigating uncharted waters, and few of us imagined the challenges we now face, both personally and professionally, while being isolated from friends, extended family, and colleagues. The operating environment going forward is also anyone’s guess. That said, following lessons learned during 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, along with best practices for virtual work, can help keep firms big and small afloat.

LEADERSHIP, LEADERSHIP, LEADERSHIP

Any crisis will serve up some market opportunities to help consumers adjust, and business leaders should seize them. Maintaining jobs while delivering solutions is an obvious win–win. As people across the planet were being told to stay home, for example, Toronto-based education technology provider Top Hat quickly moved to adopt an active learning platform designed to help boost student engagement in university classrooms to support remote teaching initiatives.

“Not everybody agrees that capitalism needs to evolve. But articulating strict old-school arguments for limited social corporate responsibility and shareholder primacy amid a pandemic sounds more than a bit ridiculous given the calls for change that were already taking place.”

But as a recent McKinsey note on the business implications of the coronavirus outbreak highlighted, this crisis “is first and foremost a human tragedy.” As such, McKinsey advised business leaders to focus on seven actions, starting with moving to ensure the safety of employees. The other six recommended actions were:

- Set up a cross-functional COVID-19 response team led by a direct report of the CEO.

- Ensure you have sufficient liquidity to weather the storm.

- Stabilize the supply chain.

- Stay close to customers and anticipate their behaviours.

- Practice your disruption plan using simulations to “define and verify their activation protocols for different phases of response.”

- Demonstrate purpose by supporting community response efforts.

While doing this, governance experts say, it is important to note that the role of corporations was already under pressure to change from inside and outside the business community prior to the coronavirus outbreak. Not everybody agrees that capitalism needs to evolve. But articulating strict old-school arguments for limited social corporate responsibility and shareholder primacy amid a pandemic sounds more than a bit ridiculous, given the calls for change that were already taking place due to the convergence of extraordinary social, political, technological, and commercial upheavals—which have led to declining public trust and radically changing sentiment toward corporate purpose and governance.

Ensuring your business does its part as a good corporate citizen isn’t just the right thing to do. When the dust settles, consumers will remember how organizations acted. Top Hat, for example, won’t just be remembered for pivoting amid disruption. After redesigning its classroom engagement offering to meet the needs of virtual teaching, the company announced that it will be providing the product to educators and students for free this semester, giving its target market a helping hand as it struggles to adapt to the pandemic’s impact on education.

Numerous distilleries will be remembered for producing hand sanitizer while many manufacturing operations will be remembered for working with government to help out on the medical equipment front. But businesses are also displaying shockingly poor judgment. Some airlines, for example, pushed discounted tickets to holiday destinations as Canadians were being warned by health officials to stay home. Swoop, WestJet’s discount brand, even attempted to be funny while marketing one-way tickets to Mexico and Las Vegas at prices it called “so low you gotta go,” while using a toilet paper image that made light of panic buying by consumers.

“It is our intent to continue operating our full schedule until restrictions are in place,” Larissa Mark, a Swoop spokeswoman, told The Globe and Mail in mid-March, adding the ad was just “a tongue-in-cheek promotion highlighting increased toilet paper demand, not the seriousness of the COVID-19 pandemic. We were drawing a parallel to the cost of stocking up on toilet paper versus the cost of being able to book a low-cost flight with Swoop; that it is more expensive to buy a stash of toilet paper than book a flight with Swoop.”

Some small businesses have also shown poor judgment, and not just by boosting prices (as I was writing this article, a mask-sporting small-business person put a flyer in my mailbox marketing soup supposedly made from an ancient and secret family recipe that supposedly kept the family in question alive during the Spanish flu thanks to immune-system-boosting ingredients).

As noted in “Why Fighting COVID-19 Requires Character,” an IBJ article by Kimberley Young Milani, the operations manager at the Ian O. Ihnatowycz Institute for Leadership, and Ivey Business School Professor Gerard Seijts, “We have all had a front row seat as the absence of humility, humanity, accountability, integrity, justice, temperance, and collaboration in some people—leaders and ordinary citizens alike—threatens to divide communities and countries, pushing us backward, not forward, when all concerned should be selflessly mitigating the spread of the virus and its often dire health implications.” This is only natural because a crisis creates heroes and villains. But it is also problematic because the world needs everyone doing their absolute best to support the efforts of healthcare workers, emergency responders, and essential service workers.

Nobody, of course, should be focused on pointing fingers at mistakes already made. The same goes for raging against the so-called “covidiots” who continue to gather in large groups. Right now, the focus of all concerned should be on keeping people safe and defeating the virus. “Don’t get stuck on stupid,” was the advice famously given to reporters by Lt. Gen. Russel Honoré (Ret.) during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. During a press conference, Honoré—who led the U.S. military’s response to numerous crisis situations, ranging from the 2002 sniper shooting spree that terrorized Washington, D.C., to the devastation and civil unrest unleashed by Mother Nature on the American South in 2005—had become frustrated by the media focus on asking backward-looking who’s-to-blame questions when critical forward-looking information was being presented for public dissemination, so he bluntly reminded them of the importance of good judgment.

The general’s message has never been more important. As Milani and Seijts point out, good judgment is the key to good leadership, and as past unprecedented events like the 9/11 terrorist attacks have shown, good leadership is what societies in crisis need most. “With the emergence of COVID-19,” they write, “leaders across all sectors and at all levels in societies worldwide face enormous challenges. How they behave and the decisions they make will separate the bad and mediocre from the truly great. And the importance of good leadership will be only magnified further as we all continue to confront highly volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous situations. These challenging and insecure times demand good judgments that are formed through, and rely upon, the coalescence of a leader’s character.”

Leading with character, of course, isn’t just about offering deals to consumers, retooling plants to produce medical supplies, or boosting pay for front-line workers. Anthony Longo, president and CEO of Longo Brothers Fruit Markets, showed the right stuff when he jumped in to help stock shelves while touring his grocery chain locations to support employees during the crisis in late March. And following this example is what other leaders should be doing as they deploy best practices to manage this crisis.

PANDEMIC CRISIS MANAGEMENT

Following the 9/11 terrorist strikes, former Ivey Professor Christine Pearson, who has authored six books on crisis management, put together a list of 10 guidelines to help organizations avert having to enter crisis mode. Her IBJ article on the topic, “A Blueprint for Crisis Management,” can be found here. But with today’s organizations already in the “wolves-at-the-gates stage,” Pearson—now a professor at the Thunderbird School of Global Management, where she is finalizing a new book on contemporary crisis management—recommends executives focus on the following five actions.

Hope for the best, prepare for the worst: According to Pearson, it is important to improve (or initiate) crisis management thinking and action, expectations, and resources as an ongoing, evolving approach throughout your organization.

Make your role model proud: When making decisions and taking actions, Pearson advises following your strongest ethical influencer. “Remember that you can’t talk your way out of things that you behave yourself into, so do the right thing from the start. Never lie. Yes, that’s right, never lie, even when circumstances are dismal. Remember, too, that facts and fake news can circle the globe in an instant. So, face into the truth and tell it quickly. If others tell your story first, you may have to dig your way out of being cast as the villain.”

Create a diverse, superb crisis management team: In today’s hyperconnected, volatile, uncertain, tech-infused global environment, Pearson notes, “crisis approaches and decisions must exceed the reach of the C-suite and the home office. You need a dedicated team who can tap into expertise, insights, needs, and resources across your organization’s vulnerabilities, opportunities, and threats. Make a brilliant selection of team members who understand the diversity (e.g., employees, sites, customers, products, services) of your organization’s reach and provide them guidance and resources to be outstanding.”

Treat your employees right: Always put employees at the top of your list for updates. As Pearson points out, they “are your first line of defense. Empower signal detection and simplify signal reporting for all employees. Don’t punish messengers of bad news, listen to them wisely. When a mistake occurs, be very slow to blame operators because contextual limitations, policies, and organizational norms are usually the root causes. When meeting with employees (F2F or virtually), give them your full attention. When making tough decisions about employees, don’t be cheap: they are your organization.”

Model healthy self-care: “Crises are marathons spiked with uphill sprints that can be treacherous and unexpected,” Pearson notes, “so you need to retain and restore your own stamina, and to be an exemplary role model for everyone else. Abide by reliable, fact-based advice (e.g., mind the 6-foot gap). Adhere stringently to the basics: eat well, get enough sleep, and exercise. Include restorative behaviors daily (e.g., break from screen-addiction, e-connect with friends and family, make time for a diversion that you enjoy).”

LEARNING FROM KATRINA (AND RITA)

In “The Dirty Dozen,” which Ivey’s leadership institute considers required reading for students of crisis management, a group of researchers from the Pacific Graduate School of Psychology (Anahita Gheytanchi, Lisa Joseph, Elaine Gierlach, Satoko Kimpara, Jennifer Housley, Zeno E. Franco, and Larry E. Beutler) identified 12 key failures of the Hurricane Katrina response effort.

The biggest mistake identified was the lack of timely, effective communication between and within state and federal agencies. The takeaway for corporations, not surprisingly, is the importance of effective communications up and down the chain of command, not to mention horizontally in peer-to-peer relationships.

“When a pandemic has everyone working from home, it is foolhardy for any business to expect something to happen just because it is supposed to happen.”

Keep in mind that most disaster management tasks rely on effective communications—which doesn’t necessarily mean a flood of communications. Indeed, when communicating in crisis mode, it is important to ensure that channels do not get clogged by irrelevant information.

The COVID-19 Response Team at Hill+Knowlton Strategies advises managers to:

- Keep key audiences current about actions your organization is taking.

- Inform employees first.

- Consider which channels are best for reaching each audience.

- Be clear about what released information means for each recipient.

- Ensure messages and actions are consistent with recommendations from health authorities.

- Monitor social platforms to catch and correct misinformation about your organization.

- Update stakeholders regularly as circumstances evolve.

Other key failures during Katrina were the lack of relief effort coordination and the existence of ambiguous authority relationships.

Good crisis management requires that all concerned know who exactly is in charge of what, especially the people expected to be in charge of something. Resources need to be pushed, not pulled, during a major crisis, which is why coordination between response teams that share a common situational awareness thanks to effective communications is so important. Simply put, when a pandemic has everyone working from home, it is foolhardy for any business to expect something to happen just because it is supposed to happen. As General Honoré frequently warns people in charge of crisis planning, “The first casualty in any emergency is the disaster plan.”

Being in charge during an emergency, of course, doesn’t mean you should issue orders without collaboration. Effective leadership involves putting ego aside and sharing control over decision making. Hierarchical thinking serves as a barrier to achieving positive outcomes, especially when facing challenges that require multiple groups to work together. Indeed, effectively deploying cross-boundary teams, especially new ones, requires an environment that battles groupthink by welcoming honest feedback.

As Professor Seijts observed years ago at an Ivey leadership conference featuring Honoré, “The U.S. Army revolutionized how it makes decisions because technology-enabled collaboration is superior to centralized decision making in today’s complex world of interconnected risks, opportunities, and challenges. And other organizations, including corporations, should do the same because collaboration across boundaries leads to bottom-up information flow, which may have saved a few U.S. banks during the financial crisis.”

LEARNING FROM CHINA

Nobody knows how bad things will get in North America. But examining the experience of Chinese manufacturing can help major employers plan for what might lie ahead.

According to research conducted by Michael Hudecheck, Dietmar Grichnik, and Joakim Wincent from the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland, and Charlotta Sirén from Australia’s University of Queensland in Brisbane, nitrogen dioxide emissions across China fell by almost 40 per cent between the start of government-imposed quarantines on January 24 and back-to-work initiatives on February 21. But the decline was far greater in industrial municipalities around Wuhan City in Hubei Province, where emissions dropped by 85 per cent in some cases. Using this data, they say a conservative loss estimate for manufacturing operations alone during the studied timeframe would be over US$215 billion.

This should scare you enough to welcome lessons learned from the experience of Chinese companies, such as those that Hudecheck, Grichnik, and Wincent published in MIT Sloan Management Review. In “How Companies Can Respond to the Coronavirus,” they highlight the need to develop remote work infrastructure, build a cash cushion that can keep you running at least a few months, anticipate how operational shocks will impact suppliers (not just you), and look out for the community. “Charity is an important response to natural disasters such as COVID-19,” they write. “In addition to simply being a good practice for ethical reasons, there are empirically established correlations between charitable activities and future financial performance, improved relations with government authorities, and reputational legitimacy.”

It is possible that Canadian efforts to stop the spread of COVID-19 will limit the economic damage. But don’t bet the company on getting off lightly. As Honoré says, “You can’t prepare for the worst if you don’t imagine it happening.”

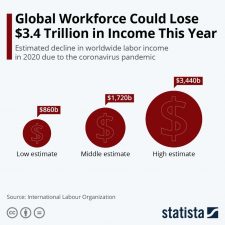

Pointing to a preliminary assessment by the International Labour Organization (ILO), Statista data journalist Felix Richter reports the world’s workforce could lose between US$860 billion and US$3.4 trillion in labor income this year alone, “which will likely prolong the negative effects of current lockdowns and make recovery from this crisis even harder.”

As a result, today is a good time to recall how the 2007 U.S. mortgage crisis was once supposedly contained before it led to the global financial crisis, which led to the Great Recession, which led to the so-called Age of Austerity, which came and went, but nothing really changed thanks to historically low interest rates that pushed many people to focus their nest-egg investments on equities markets rather than safer financial products like GICs.

Governments across the global economy are now fighting to counter the impact of the pandemic with unprecedented stimulus packages while the latest round of emergency monetary policy measures encourage debt holders to borrow even more. Although it is hard to imagine any other actions reasonably being taken under the circumstances, it isn’t hard to image the potential long-term implications. Simply put, the world has collectively banded together to outlaw financial market pain and economic downturns for a long time, allowing political leaders, market players and consumers to ignore the wisdom of using good times to prepare for bad. “We do not allow default now except for the little guy,” says influential American money manager David Kotok, so now the world will “borrow more and finance it with manipulative low rates by central banks. That will continue until the next great inflation arrives.”

Kotok, who has been passionately trying to raise awareness of pandemic-related risks for years as chief investment officer at Cumberland Advisors, says this won’t happen today, but when uncontrolled inflation eventually rears its head it “will come with a vengeance.”

As Hudecheck, Grichnik, and Wincent concluded: “Managers must be prepared to accept that what we are now observing represents a new reality: Diseases and other forms of ecological disasters are very real global threats to operational continuity.”

Whatever the future holds, Ivey Professor Andreas Schotter advises multinationals to make sure they are keeping track of all identified vulnerabilities (within and outside the organization) as they scramble to maintain operations because retreating from globalization is not a viable long-term strategy and the need to develop more resilience, agility and contingencies within international networks existed before the global value chains were being strained by COVID-19.

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

In a pre-pandemic address to The Empire Club of Canada, Rahul Bhardwaj, president and CEO of the Institute of Corporate Directors, noted that today’s directors need to be less “nose in, fingers out,” meaning less hands-off than board members of yesteryear, to best help organizations successfully navigate the unprecedented challenges and waves of disruption that our world currently faces with a view to the long term. This wasn’t a call for a management takeover by directors. It was a call for boards and managers to better utilize the many years of experience that surround most boardroom tables.

And as this crisis unfolds, Bhardwaj says the need for more active and engaged directors has never been greater. That said, the need for an effective working relationship between board chairs and corporate CEOs has also never been more important in order to ensure that one eye remains on the long term and that every move made in the short term is communicated effectively to all stakeholders, including regulators, while representing the company’s culture and values.

Bhardwaj emphasizes that everything directors have been taught about employing “hindsight, oversight, and foresight” effectively is more important than ever. “This is really where the rubber hits the road for boards.”

The ICD recommends that corporate directors make sure they have the correct answers to the following 10 questions:

- Do we have an adequate crisis communications plan in place for all stakeholders?

- Are there “disclosure” requirements that we need to consider?

- How and when should we be communicating to our advisors, including legal, crisis communications, financial, and government relations advisors?

- Do we understand our economic exposure to COVID-19, including the downstream impact?

- What is our response plan if our workforce is exposed to COVID-19?

- Have we identified how our key partners and stakeholders may be impacted by this situation?

- Do we have the right business continuity plan for this situation?

- How do we make sure that we are getting timely, verifiable, and authoritative information?

- What are the key metrics for our business that the board needs from management to make key decisions going forward?

- What is the right cadence of reporting to the board during this crisis? Does it warrant an ad hoc committee of the board?

The ICD also has created a resource site to assist board members to perform their function during the pandemic that can be found here.

ADVICE FOR ENTREPRENEURS

Early-stage ventures face unique challenges, so here is some actionable advice from entrepreneur and Ivey instructor Eric Janssen, who started his first company in university years ago, building an online network linking young company founders with business partners, mentors, and other resources.

Try to increase revenue: “This is the obvious one,” Janssen says, “but likely—at least in the coming weeks—the most challenging to execute. Retail, food services, transportation, entertainment, recreation, and hospitality have been disproportionately impacted, but some companies are in expansion mode. Major hiring announcements have come from Amazon and Walmart, and delivery services, in general, are surging. Businesses with a strong online presence are in the best position to maintain sales. For salespeople, I advocate caring over content. Right now, simply checking in with your current customers, and letting them know that you’re thinking about them, can go a long way.”

Move to collect receivables: As Janssen notes, “Smaller companies are surprisingly lax with payment terms. Sometimes it’s because they don’t feel that they can impose their own terms on the other (sometimes larger) clients that they work with; often though it’s because there are so many other activities crying for attention that ensuring payments are received in a timely manner isn’t any one person’s priority. Early-stage companies are often too small to have a dedicated accounting department or collections team, and so collecting receivables falls on anyone and everyone—or no one. When cash is tight, I recommend generating a weekly receivables summary with amounts owing by account, and days overdue. Review this on a weekly team call, and make each account one person’s responsibility to follow up.”

Delay payables: “I’m not suggesting you damage any relationships with suppliers, but a pre-emptive call with your largest creditors asking for some extended payment terms can go a long way.”

Cut non-essential spending: “Have you ever lost a credit card?” Janssen asks, noting the “process of cancelling a card and having to re-add all of the monthly subscriptions is sometimes an eye-opener. Are there any areas of your business that are like the monthly cable subscription that you really don’t need anymore? Ideas here are: marketing channels that haven’t proven a positive ROI, office/desk space that is not being used, ‘nice to have; software subscriptions that can be put on hold.”

Consider temporary layoffs: “In all situations,” Janssen says, “laying off employees is the worst-case scenario. Thankfully, our government has made this process slightly less painful for employees by expediting the EI process and offering various other incentives to help employees through this difficult time. While layoffs are a horrible decision to have to make, the trade-off here is acting too late and losing the entire company. As a business owner/leader you have an obligation to ensure the business continues to operate, and in the short term that might mean layoffs so that the business has a chance to survive in the long term. I’d rather make the hard decisions now and have a fighting chance at survival than react too slow and lose the company and all of the jobs for good.”

WORKING FROM HOME 101

In his “Grow Even Faster” newsletter for marketing and sales professionals, B2B consultant Mark Evans, the author of Marketing Spark, drew on his previous experience working remotely to offer the following working-from home (WFH) tips to the cubicle crowd unused to isolation.

- Take a shower. Don’t just head downstairs for coffee and then slide into the home office.

- Get dressed. No, a tracksuit doesn’t count.

- Eat breakfast & lunch. Breakfast is the most important meal of the deal. Lunch is a good excuse to take a break.

- Take coffee/tea breaks. Put a “Starbucks” label on your coffee maker and it’ll be just like being at work.

- Define “working hours.” WFH is not a 24/7 proposition simply because you’re home all day.

- Establish daily goals and start with the biggest priorities. Write ’em down, and display them prominently.

- Be disciplined with social media and email. Twitter and your inbox will happily exist for hours without you. Really.

- Take care of your body. There are many excellent (and free) workout websites (e.g., fitnessblender.com). An easy way to start is the 7-minute workout.

- Stay connected with friends and family—phone, text, Zoom, Skype, FaceTime, DM. It will keep you and the important people in your life sane.

- Be well. Practice social distancing. Be good to each other.

MANAGING VIRTUAL TEAMS

As the working world struggles to maintain business continuity via a massive expansion of virtual teams, it is important for managers to understand the associated pros and cons.

According to research conducted by the Society for Human Resource Management, virtual teams can improve productivity while saving the time and cost of travel, especially when it comes to brainstorming, project planning, and setting goals. But developing trust, maintaining morale, monitoring performance, and managing conflict can become more difficult when people are distributed. Deprived of visual cues, virtual teams also have a harder time developing a shared understanding, while collaboration can be hindered by time zones and technology barriers.

The good news, as noted by management consultants Rick Lepsinger and Darleen DeRosa in the IBJ article “How to Lead an Effective Virtual Team,” is that avoiding failure isn’t difficult, it just requires following some best practices.

And if you really want to supercharge engagement, Derrick Neufeld, an Ivey Professor of information systems, and Yulin Fang of the City University of Hong Kong, say it can pay to understand situated learning and identity construction. For more on this topic, see their IBJ article “Nurturing Virtual Teams,” which offers concrete steps to help organizations increase virtual team member engagement based on research into distributed open-source projects.

While doing his doctoral dissertation years ago, Neufeld also conducted research on teleworkers that he thinks remains relevant and bodes well for organizations today.

“Not everything was positive,” Neufeld says, noting that an “out-of-sight, out-of-mind mentality” sometimes develops and that working from home was tougher for parents with young children. There was also some difficulty due to “lost water-cooler updates.” But sending employees home to work was associated with positive outcomes as tension and overload decreased considerably while both job satisfaction and productivity both increased significantly. Marginal improvements were also found in communication, coordination, flexibility, and autonomy.

With workplace isolation increasing, of course, it is important for managers to note that mental health issues need more executive attention before all hell breaks loose (see “Creating a Supportive Mental Health Culture” by Accenture’s Barbara Harvey and Regina Maruca).

To maintain morale, Ivey faculty member David Wood suggests hosting end-of-week team parties on Zoom or similar platforms to give employees a virtual meeting that they can expect to enjoy, not dread. “Invite everyone to attend a Zoom meeting where they don’t have to worry about appearance or attire or even being prepared,” he says. “Offer prizes for the most embarrassing virtual meeting moment of the week, or best background. Give isolated employees a chance to connect that’s not related to work and others who have to fight the distraction that comes from working next to a teething two-year-old or snoring dogs a chance to not worry about it.”

If you are holding a large party, Ivey Professor Darren Meister offers the following breakout room party advice:

- Consider breakout parties with smaller groups, keeping the numbers to nine, which shows up well on a screen.

- Move to breakouts for 10-minute events so they end before getting boring. Then back to the big group.

- Don’t let software pick the facilitator. Do it randomly using something like the next team member birthday or person with the best story behind their middle name to get people talking.

- Get people to name themselves on the screen so they aren’t just a telephone number.

- Don’t worry about getting everyone involved because some people are going to join just for the distraction. They’re just happy for company.

- Have specific topics in mind to keep the conversation fun. But be sensitive to the fact that lots of people are self-isolating alone and it’s possible that hearing about other people’s families and pets will make some of them feel worse. One person’s Zoom chaos can be another person’s wish.

Finally, as Ivey Professor Paul Beamish notes, everyone in business should maintain perspective. Working with Schotter, Beamish has spent about a decade researching the hassle factor, a measure of 11 foreign market conditions that make expanding operations difficult. This data can help international companies plan foreign investments wisely. But it can also be used to remind people in advanced economies that while we rightfully worry about the coronavirus spreading, the fallout from this pandemic is likely to be far worse in poor countries.

“Imagine,” Beamish says, “if you lived in one of the countries that scores poorly when the hassle factor is measured, and you don’t have the option of leaving. What a visitor or investor typically considers a hassle under regular conditions might make the difference between life and death for locals.”