As an intellectual, legal professional, working mom, and gender freedom fighter, there is no question that U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg—who recently lost her latest battle with cancer—earned her “Notorious RBG” moniker. But despite her reputation as a liberal superhero and feminist rock star, she wasn’t the first woman to attend Harvard Law or the first woman to make the Harvard Law Review. RBG wasn’t even the first woman to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court. Her trailblazing was as a legal strategist who managed to do what others had tried and failed to do—open male eyes to the existence of sex-based discrimination—using a mind that defied stereotypes.

When nominating RBG to the Supreme Court in 1993, former U.S. President Bill Clinton insisted “Ruth Bader Ginsburg cannot be called a liberal or a conservative; she has proved herself too thoughtful for such labels.” The thoughtfulness of RBG’s character that Clinton noted enabled the jurist in her quest to constitutionalize social change by complementing her competencies and commitment. And we submit that this might be her greatest legacy, setting a much-needed example for others who aspire to bring about significant societal change.

As America’s highest court enters a new era—one marked by the political dispute over the confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett as RBG’s replacement—this article aims to highlight how today’s law students, along with professionals of all genders and stripes, especially ones in leadership positions, can learn a lot from studying how Ginsburg’s upbringing and interests, including her love of music, helped her maintain a relatively balanced character, which, in turn, provided her with practical wisdom, or what Aristotle called “phronesis.”

Practical wisdom allows people to set the best course as they navigate complex challenges using a higher form of judgment that isn’t overly influenced by an individual’s ego, ambition, and courage, which are kept in check by other dimensions of character, such as collaboration, temperance, humility, and empathy. Given the challenges our world currently faces, practical wisdom has never been more important. Unfortunately, it cannot be obtained by simply acquiring knowledge and learning rules. As explained by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Aristotle insisted: “We must also acquire, through practice, those deliberative, emotional, and social skills that enable us to put our general understanding of well-being into practice in ways that are suitable to each occasion.”

THE DEVELOPMENT OF SUPREME JUDGMENT

The second child of working-class Jewish parents, Joan Ruth Bader was born in Brooklyn, New York, on March 15, 1933, during the height of the Great Depression. Nathan and Celia Bader—who worked as a haberdasher and factory worker, respectively—lost their first daughter, Marilyn, to meningitis 14 months later, and they did not raise her sister to be a liberal firebrand. But RBG’s development was clearly heavily influenced early on by her mother, who excelled in school and finished high school at only 15.

According to family lore, Celia Bader—who died the day before RBG’s high school graduation—possessed a love of reading that was so strong that it once broke her nose. As the story goes, she fell into an open street cellar because she was walking with her face buried in a book. Through frequent trips to the library, this passion for learning was passed from mother to daughter, along with the strength and courage that Celia Bader displayed while battling cervical cancer.

As highlighted in the documentary RBG by Julie Cohen and Betsy West, Celia Bader also consciously influenced her daughter’s development by repeatedly driving home the importance of a) being “a lady,” and b) being “independent.” To RBG’s mother, of course, being a lady meant not allowing oneself to be overcome by useless emotions like anger, while being independent required developing the ability to fend for yourself—although Celia Bader considered it acceptable to find a worthy “Prince Charming” to help in this regard, which RBG did at Cornell University when she met Martin Ginsburg, who she famously described as “the first boy I ever knew who cared I had a brain.”

When Ginsburg attended Cornell, the school was considered an ideal educational environment for female students because its demographics improved the chances of finding a husband. But attending university during the McCarthy era landed RBG more than a supportive life partner and bachelor’s degree in government—it sparked her fire to help make America live up to its promise. Although RBG wanted to fight for civil rights as a lawyer, not a street protester, her family only accepted her chosen career path after she married Martin, who was already working toward a Harvard Law degree when the couple married in 1954.

Martin Ginsburg’s legal studies were interrupted by a two-year ROTC stint at Fort Sill, Oklahoma—where Jane, the first of the couple’s two children, was born. During this period, RBG was offered a claims manager position at the local Social Security office, which was rescinded and replaced by a lower-level typist position when the office learned she was pregnant (this form of discrimination was legal at the time). Ginsburg’s husband returned to Harvard in 1956, and she joined him as a first-year law student.

As one of nine women in a class of hundreds, she constantly felt on display. She also repeatedly faced indignities such as being refused entry to a male-only library or being asked by the school’s Dean to justify taking a Harvard degree away from a man. Ginsburg’s legal studies were further challenged when Martin was diagnosed with testicular cancer. Forgoing sleep, she helped her husband overcome his disease and still graduate, putting together notes for him to study and typing his papers, all while doing her own studies, managing the house, and raising a child. Against these odds, RBG excelled academically, earning a prestigious place on the Harvard Law Review.

While in school, RBG gave up more than sleep to support her family. Instead of graduating with a Harvard-branded degree, she selflessly transferred to Columbia Law School to keep the family together after Martin graduated and landed a job in New York. At Columbia, RBG continued to manage her responsibilities at home and school through relentless determination. But despite making the Columbia Law Review and graduating at the top of her class in 1959, she still hit a brick wall when looking for a job with a New York law firm.

“I struck out on three grounds,” as she later put it. “I was Jewish, a woman, and a mother. The first raised one eyebrow; the second, two; the third made me indubitably inadmissible.”

“RBG’s treatment as a second-class citizen by society could have conspired with the trials and tribulations that she faced on the home front to overcome her drive and ambition with feelings of anger and resentment.”

A New York District judge eventually offered RBG a clerkship thanks to a Columbia professor who reportedly refused to recommend anyone else. Despite this clerkship, the doors at major law firms remained closed to RBG in the 1960s, so she entered academia, working on a comparative law project studying the Swedish legal system before landing a teaching position at Rutgers Law School, where she taught early classes on women and the law. Before giving birth to her son James in 1965, she hid her pregnancy from the school to avoid workplace discrimination.

As RBG once noted, she grew up “with the smell of death.” And her treatment as a second-class citizen by society could have conspired with the trials and tribulations that she faced on the home front to overcome her drive and ambition with feelings of anger and resentment.

Alternatively, these same experiences could have supercharged her passion to make the world a better place, counterproductively fueling it to the point of hindering her ability to serve as an effective agent of change. But with her ambition and drive tempered by humility and humanity, she managed to defeat the challenges life presented her and go on to win five out of six gender-equality cases argued before the Supreme Court.

In the movie On the Basis of Sex, RBG’s nephew Daniel Stiepleman chronicles his aunt’s rise as a trailblazing legal strategist, focusing on Moritz v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, the first gender-discrimination case that Ginsburg argued in court. The case in question involved an appeal by Charles Moritz, who was denied a tax credit available to caregivers because the law at the time wasn’t formulated by people who could imagine a single man being a caregiver.

When defending the IRS decision to deny Moritz a deduction, government lawyers insisted that there was a rational basis for denying the claim based upon the traditional distribution of family responsibilities and that doing so fit within the broad discretion of Congress in providing deductions. But RBG convinced the court to conclude that the tax statute in question “did not make the challenged distinction as part of a scheme dealing with the varying burdens of dependents’ care borne of taxpayers, but instead made a special discrimination premised on sex alone, which cannot stand.” And in the movie, just before we see Ginsburg (played by actor Felicity Jones) present her argument, the camera rolls across the following Thomas Hobbes quote displayed on a courtroom wall: “Reason is the soul of the law.”

The same can be said about RBG’s balanced character. After all, it was her empathy that allowed her to figure out that using discrimination against men to fight discrimination against women was the best way to open male eyes to the fact that a rational reading of equal protection principles in the U.S. Constitution calls into question any difference in the treatment of individuals based upon sex, regardless of historical norms.

While judges in the Moritz case were still deliberating, the reasoning that RBG developed to eventually win the 63-year-old bachelor a minor tax refund was used in another case called Reed v Reed. This helped the ACLU Women’s Rights Project—which RBG co-founded—convince the Supreme Court to find for the first time that a classification based on sex was unconstitutional. In this case, the ACLU successfully challenged the automatic preference of men over women as administrators of estates. And as the ACLU highlights on its website, this was done in the same high court that had unanimously upheld in 1961 the constitutionality of discriminating against women when selecting juries on the grounds that a woman’s place is “at the center of home and family life.”

The rest, as they say, is history. In addition to establishing the legal landscape to challenge gender discrimination in the 1970s, RBG broke a glass ceiling to become the first tenured female professor at Columbia Law School. In 1980, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter nominated her to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, where her reputation for being skillful at consensus-building and articulating persuasive arguments was solidified.

LINKING GOOD JUDGMENT AND CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT

Educators at Western University’s law and business schools see Ginsburg as an ideal case study because of the strength of her character, commitment, and competence, which are equally key components of the 3C framework for good leadership.

Until recently, there has been an overweight focus on developing competencies in professional development circles. But following the leadership failures that contributed to the 2008 financial crisis, Ivey Business School researchers focused their attention on how each of the three components of the 3C framework needs to be in place to elevate leadership via the development of consistently good judgment.

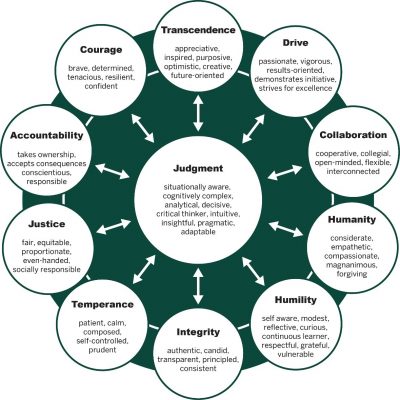

This work identified 11 virtuous dimensions of character and related traits (see Exhibit 1) that support long-term career success via the development of sound judgment—but only when working together to prevent each of them from becoming vices. Drive, for example, can lead leaders who lack temperance and humility to take unwarranted risks (think banking and subprime mortgages).

11 Dimensions of Leader Character

11 Dimensions of Leader Character

A key finding of Ivey’s research into leader character was that individuals can be assessed to determine where character deficiencies exist (a Leadership Character Insight Assessment tool developed by Ivey in partnership with SIGMA Assessment Systems can be found here). Furthermore, identified weaknesses can be addressed using character-focused leadership development techniques—including improvisation and music (see the IBJ article “The Sound of Leadership”)—that are now being deployed by forward-looking organizations in both the public and private sectors.

Keep in mind that the need for leaders to deploy character has never been greater because of the challenges we all face today. But exercising and developing character is an ongoing process because nobody’s various dimensions of character are perfectly balanced at birth and our experiences constantly strengthen or weaken some dimensions more than others. And when it comes to people in leadership positions, Ivey research has found that one of the character dimensions that tends to need strengthening is temperance, which is why RBG makes such a great case study.

Studying the impact of character on Ginsburg’s judgment can also benefit the legal profession, which is very knowledge-based in orientation. Students are taught to base their judgment on the rules of the law. But as highlighted by a survey of more than 24,000 lawyers across the United States—conducted by the University of Denver’s Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System (IAALS)—law practitioners know that’s not enough.

As the IAALS pointed out in a report, “When we talk about what makes people—not just lawyers— successful we have come to accept that they require some threshold intelligence quotient (IQ) and, in more recent years, that they also require a favorable emotional intelligence (EQ). Our findings suggest that lawyers also require some level of character quotient (CQ).”

Unfortunately, the report in question didn’t define what character was or how it operates, which is another reason why RBG makes such a great case study.

Influenced by a healthy range of character dimensions, Ginsburg clearly developed practical wisdom, which kept her open-minded and attuned to the broader issues while ensuring her judgment was elevated beyond the IQ level (cognitively complex, analytical, decisive, critical thinker, etc.). This is why she defied stereotypes as a collaborator and passionate driver of change. As noted in the Politico article “The Surprising Conservatism of Ruth Bader Ginsburg,” RBG sided with the conservative wing of the court—“to the chagrin of environmentalists”—in endorsing the construction of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline beneath the Appalachian Trail, as well as in reversing a decision of the “famously liberal-leaning 9th Circuit” on the Trump administration’s deportation of people seeking asylum in the United States.

“Although she never articulated it exactly this way, RBG’s passion for opera contributed to her career success by constantly exercising the dimensions of her character that kept her grounded.”

Put simply, as evidenced by Ginsburg’s relationship with the late Justice Antonin Scalia—who served as her ideological counterweight on the Supreme Court—it is possible for someone to possess the intellect and ambition required to reach the highest level of their profession and still maintain the ability to hear and collaborate with others, even people with whom they frequently and passionately disagree. It just takes also having the humility and humanity required to keep your temperance strong, mind open, and ego in check.

Although she never articulated it exactly this way, RBG’s passion for opera contributed to her career success by constantly exercising the dimensions of her character that kept her grounded. As she explained, “When I am at an opera, I get totally carried away. I don’t think about the case that’s coming up next week or the brief I am in the middle of [writing]. I am overwhelmed by the beauty of the music, the drama. It is like an electric current going through me.” This electric current she describes essentially recharged her sense of justice, humanity, transcendence, and humility. RBG was also humbled by opera performers, who possessed skills she coveted but knew she would never acquire.

As The Economist noted: “Opera, after the law, was her great love, the only place where she could leave the legal world behind. When she worked on her opinions, often into the small hours if her husband Marty was not around to make her go to bed, she would usually have opera, or some other beautiful music, playing in the background. The talent she most coveted was to have a glorious voice, like Renata Tebaldi perhaps. As it was, she sang only in the shower and in her dreams.”

This article has focused on the factors that influenced Ginsburg’s character, but she is also a case study in commitment, and not just in her fight against discrimination. Indeed, as a USA Today headline put it, Ginsburg v. cancer was a “remarkable fight.”

Over the course of two decades, RBG fought pancreatic, lung, and colon cancer, but her commitment to serving justice and making America live up to its billing kept her on the job while undergoing painful treatments, which included chemotherapy and the removal of her spleen, parts of her pancreas, and cancerous growths from her lungs. According to RBG, retired Justice Sandra Day O’Connor offered her the following advice based upon her own experience with battling cancer as a high court judge: “when you’re up to chemotherapy, you do it on Friday, Friday afternoon. You’ll get over it over the weekend, and you’ll be able to come to the court on Monday.”

RBG’s commitment to remaining on the court for as long as she mentally and physically could do the job was also impressive. Created by Ginsburg’s personal trainer, Bryant Johnson, the RBG Workout—an hour-long regimen of wall squats and medicine ball pushups that RBG did religiously twice a week—inspired health enthusiasts and Saturday Night Live comedy writers alike.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg deserves to be admired (along with her husband) for how her character, commitment, and competencies joined forces to help make the world she left a better place than the one she entered. But systemic discrimination remains a burning issue and it is just one of our world’s significant challenges, which is why the practical wisdom of RBG should not be notorious—it should be commonplace in law firms, corporate boardrooms, and political offices around the planet. We can all learn from how she managed to overcome so much, and accomplish so much, with so much grace, and we can put the leadership lessons she represents into action by elevating the development of character alongside the development of commitment and competencies in our professional development programs and practices.

RBG, please RIP.

I fully enjoyed the Ginsburg write-up – helps to understand what this woman was all about. Incredibly well written.

However, you could have left out the reference to systemic racism. That, in my mind, is a fine example of fatuous commentary. It is used continuously by people who have not the faintest idea what it means. Racism is bad enough as is … and we know what the term means … and it will always be with us, to some extent. The best we can hope for is to blunt its edges. No need to lose energy trying to establish that it is not just racism … it is “systemic” racism.